After Biber’s Rosary (Mystery) Sonatas – What Next?

Mark Seow

Thursday, June 29, 2023

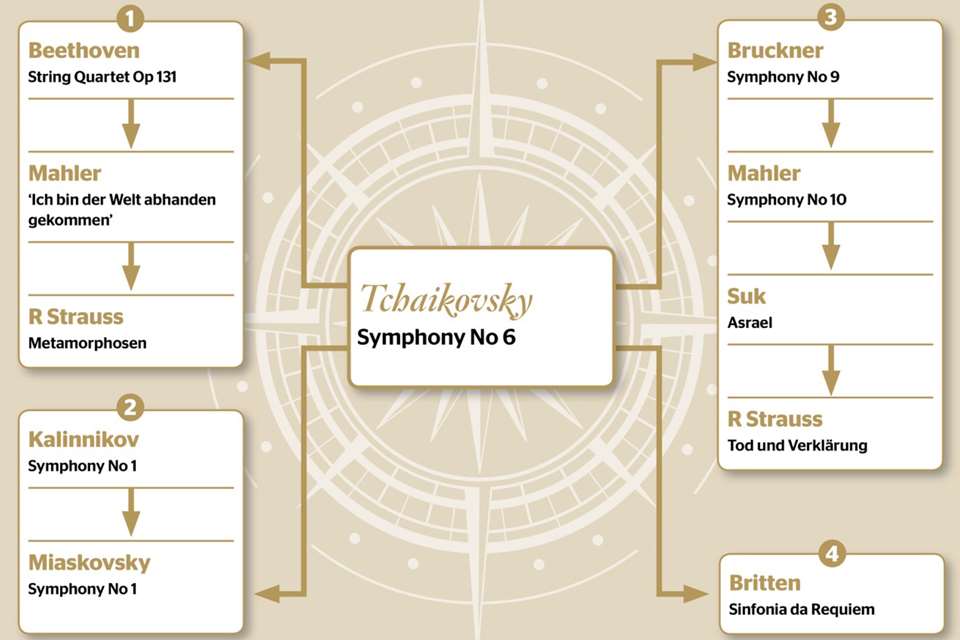

In our guide to further listening, Mark Seow starts with Biber’s Rosary (Mystery) Sonatas – and the ensuing musical journey takes some weird and wonderful turns

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter