Rachmaninov's Etudes-tableaux, Op 39 – which recording should you buy?

Bryce Morrison

Friday, April 8, 2016

The essence of these piano pieces is, as Bryce Morrison finds, best captured by the Russian piano elite

The transition in critical estimates of Rachmaninov from ‘salon’ (or, worse still, ‘popular’) to ‘serious’ has been slow. Today, the 1927 edition of Grove claiming that he is ‘too cosmopolitan in idiom to be of lasting significance’ is laughed to scorn (with Ashkenazy prominent among the merrymakers). From the same period: ‘The beauty of his music is overwhelming…only a Puritan could fail to respond to it’ (The Record Guide, 1955, edited by Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor); while for Boris Berezovsky, stung by what he sees as musical snobbery, ‘Rachmaninov is a Russian Bach, his music alive with contrapuntal magic and complexity.’ Point counterpoint! The sticking, and now tipping, point surely lies in Rachmaninov’s unapologetic emotionalism, a quality dear to the Russian soul but one viewed with suspicion and even distaste by a more academic and circumspect mentality.

Rachmaninov is now no longer exclusive to Russia but is performed by pianists of virtually every nationality – even the French have erased their once snobbish disdain (for Nadia Boulanger, chocolate was preferable to a composer she found ‘très vulgaire’). Yet if Rachmaninov’s Romantic rhetoric and deep-dyed melancholy are central to Russia, it must be said that even Sviatoslav Richter, Rachmaninov pianist par excellence, shied away from the emotional storms of Op 39 No 5, declaring, ‘Although I love listening to it I try to avoid playing such music as it makes me feel completely naked emotionally. But if you decide to perform it, be good enough to undress.’

If proof of Rachmaninov’s stature were needed it would surely be provided by the Etudes-tableaux, Op 39, his second book of studies and a notable advance in richness and complexity on the earlier but very attractive Op 33 set. Completed in 1917, the year of the Russian Revolution and the time of the composer’s enforced exile, they mirror a dark and clouded ecstasy only resolved in a defiant major-key conclusion. The title Etudes-tableaux invites reduction. Mendelssohn thought music too precise rather than too vague for language, and to talk of ‘waves’ (No 1) or ‘seagulls’ (No 2), let alone Rachmaninov’s own description of No 7 as a funeral occupied by ‘fine incident and hopeless rain’, limits rather than expands Op 39’s stature.

Ferocious and tormenting in its demands, Op 39 is designed for those whose outsize technical command is complemented by a born feel for turbulence and upheaval. Milk and water as opposed to Russian vodka play into the hands of those few who dismiss qualities alien to their own restricted natures. And here the question of nationalism once again rears its head. There are, of course, some notable exceptions, and yet can it be coincidental that the greatest Rachmaninov pianists are Russian? If pride of place went to four Spanish pianists in my Gramophone Collection on Albéniz’s Iberia, a similar situation obtains in the case of Rachmaninov’s Op 39.

Full sets that cry out for more. . .

And now to complete cycles, commencing with lesser mortals. As Rubinstein once remarked, there’s a wide gulf between ‘first-raters’ and ‘others’, as he suitably placed himself, Horowitz, Michelangeli, Richter, Gilels, Arrau et al in the first group.

Let’s begin with the indefatigable Idil Biret (whose discography even includes Brahms’s 51 Exercises), who shows herself indifferent to much beyond surface fluency in No 1; and why so fast in No 2 (admittedly a common failing) when it is marked lento? Inclined to go her own way rather than Rachmaninov’s, her skittish facility is an undernourished alternative to grandeur. John Lill (joint first-prize winner in the 1970 International Tchaikovsky Competition) offers a weightier experience – indeed, is solid as the proverbial rock. But it would be hard to find a more studio-bound performance, one that fails to read above, between and below the lines. To evoke Muriel Spark’s iconic Jean Brodie: ‘Safety does not come first. Goodness, Truth, and Beauty come first.’

Again, if you are looking for a higher degree of voltage or edge you will hardly find it from Artur Pizarro in the first volume of his projected cycle of the complete solo works. Tempos are moderate, the emotional temperature low, and if Poulenc, stung by an overly dry way with his music, declared, ‘Put more butter in the sauce,’ I can only imagine a pianist of true Russian vintage, on hearing Pizarro, begging for more pep and a higher degree of intensity. For Pizarro, greater ferocity would be abrasive, yet these performances are for those who, perversely, enjoy a soothing, nightcap view of Rachmaninov. Writing of Martin Cousin, an American critic exclaimed, ‘This guy’s the Real Deal!’ But again there is too little on offer in his Rachmaninov beyond a civilised veneer.

Hanna Shybayeva, too, takes a somnolent view. And although she is admirable in the painful, limping progress of No 2 (music that surely reaches its apogee in Debussy’s prelude Des pas sur la neige), she is the reverse of extrovert in Nos 4-7. Per contra, Barry Snyder relishes storms and stresses, but his lack of willingness to explore the lower reaches of the dynamic spectrum make for an experience more blistering than musical.

Stepping closer to the mark

With Jean Philippe-Collard you listen to another level of achievement – a big-handed reaction to traditional French pianism (to what he scathingly calls Marguerite Long’s ‘diggy-diggy-dee’ school of playing). He takes No 6 by the throat (Pizarro has the wolf and Red Riding Hood on the best of terms), and there is a sense, too, in No 7 of music almost too dark for utterance. With John Ogdon you feel only an intermittent engagement with his task. Recorded under more than trying conditions, he was already on the cusp of a mental breakdown. True, in No 5 he fires up, thus making a nonsense of the popular ‘gentle giant’ myth associated with him; but the climax of No 2 is thrown away, No 6 starts with a disturbing error (something that in the general confusion slipped the producer’s notice), and if he is again gripping in parts of No 7 the overall impression is of a pianist no longer in command of his situation. Ogdon played and recorded too much, and too many of these performances hardly withstand close scrutiny, their air of disillusion a far cry from his early brilliance.

Freddy Kempf offers a less charged experience, but his immense facility finds him moving effortlessly from inwardness to an explosive energy. A major talent whose musical grace and fluency in No 2 rises to a truly savage anger, he makes the storm clouds scud across a desolating landscape. There’s no lack of ardour from Howard Shelley who is musicianly to the core even if – like Valerie Tryon in her early black disc (the first LP of Op 39) – he sees Rachmaninov at his most dramatic as in need of a cooling agent. Nicholas Angelich, whose recording I underestimated at an earlier stage, may be more plaintive than savage in No 5 but he is graceful and winning in the initially gentle undulations of No 8 and, for once, truly lento in No 2.

Yuri Paterson-Olenich’s playing brims over with ideas, a testament to his ardour and dedication. His Russian, rather than his English, temperament (he is Anglo-Russian) is to the fore even when his fast-flowing tempo for No 2 finds him shying away from its pain. Less virtuosic than others, his musical instincts rarely fail him. Vladimir Ovchinnikov also lacks voltage, but is never less than interesting, is musing and poetic in No 2 but unable to generate sufficient tension in the madcap chase of No 6. Finally in this group, Rustem Hayroudinoff (a ‘benchmark recording’ for one of my colleagues) is adept at locating a dark undertow in the work of a composer who once confessed, ‘Sometimes I think someone will come down the chimney and murder me’. Here is all the rise and fall of a cruel sea in No 1, a cool but always expressive way with No 2. Disappointingly relaxed in No 9’s major-key triumph, he is personal and eloquent in minor-key abyss.

Incomplete – but not insignificant

By way of intermission, I should say that no admirer of the Rachmaninov Etudes-tableaux could do without passing mention of several incomplete versions. No pianist has ever equalled, let alone excelled, Sviatoslav Richter in Rachmaninov, and in his live performance of Op 39 Nos 1, 2, 3, 4, 7 and 9 he makes you recall King Lear’s defiance (‘Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks!’). Then there is Vladimir Horowitz, who once told me he could play like an angel. His teasing indulgence and theatricality in Nos 7 and 9 may be enthralling but it is hardly angelic. Early in his career the young Evgeny Kissin put pianists twice his age in the shade in Nos 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 9, and the Russians themselves would cry out were I not to mention Van Cliburn in No 5. For Russians, Cliburn, at the start of his career, was ‘one of us’.

True greats in complete sets

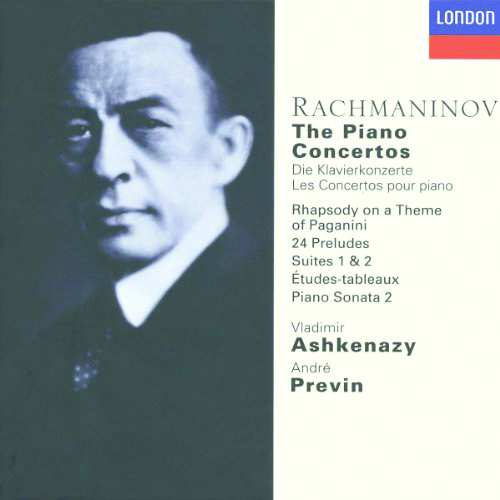

And so finally to the truest kings and princes of Russian pianistic glory in a complete Op 39 (no queens or princesses on this occasion). Vladimir Ashkenazy’s recording (part of his complete cycle of concertos, the Paganini Rhapsody and the solo piano music) is of a daunting authority, positively commanding your attention at every point. Muscles bulge and ripple in a manner remote from his early, relatively lightweight playing, which he later came to consider superficial. ‘Do you like pianists who fidget their fingers over the keys?’ he asked me after a masterclass given to some luckless American students. I cannot resist adding that I was part of this occasion, having been invited to play the first two of the Op 39 études. Mercifully, Ashkenazy’s intimidating scrutiny took so long and was so pronounced that time ran out and I never played for him; otherwise I am not sure I would be here to tell the tale! In common with many Russian musicians, Ashkenazy’s personal charm does not extend to piano playing lacking in total technical authority and musical conviction. But, answering his own rhetorical question, his Op 39 études are of an intimidating strength and proficiency.

He packs a formidable punch in No 1 (more so than in his earlier recording), his trenchancy emphasised by Decca’s glittering or clangorous (according to taste) sound. He rises to great heights of declamation in No 2, making you realise that despite the denigration of his early years, when all forms of intellectual enquiry were crushed, he remains true to his Russian roots. Scriabin and Rachmaninov in particular have remained central to his vast repertoire. Vilified in his native land, his name was later removed from all official records. He literally became a non-person. I make this point because, as his playing declares, music survives above and beyond such dire conditions. Even when you find him more gusty than measured or relentless in the climax of No 7 with its earlier lamentoso outcries and hints of the Russian liturgy, you can only wonder at his visceral attack in No 5 and his dazzling scherzando finish to No 8. Ashkenazy, despite his worldwide, cosmopolitan career, remains gloriously true to the Russian idiom.

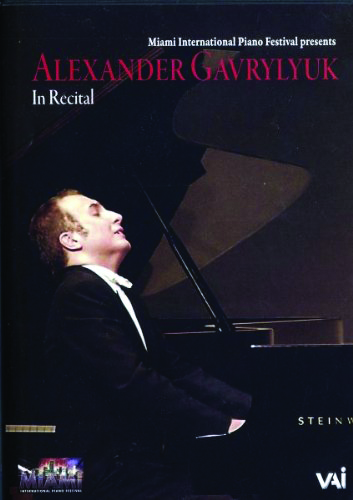

And then there is Alexander Gavrylyuk, who was 22 when he was recorded in Miami, and already possessed with the trenchancy and emotional commitment of the great Russian pianists. He is an international prizewinner who (unlike many who fail to survive their early success) has continued to cause a furore, performing with the most celebrated orchestras and conductors, including Ashkenazy, with whom he recorded the complete Rachmaninov concertos and Paganini Rhapsody. After a brief sojourn in Australia he returned to his native Ukraine, and although his repertoire is wide-ranging, his focus on the Romantics (plus Bach and Mozart), and Russian Romantics in particular, tells its own tale. His greatest success, as on this recording, has been in Rachmaninov, and here he makes Op 39 the centerpiece of his programme.

In No 1 his relatively slow tempo uncovers a sinister undertow beneath the hyperactive surface, finding time to inflect even the busiest pages with freedom, colour and imagination. What intensity, too, in every agonised page of No 2, where he plays as if his life depends on every note. He is gnomic, even playful – a view that’s fascinatingly different from Nikolai Lugansky’s wintry drive and severity in the dancing measures of No 4. In extreme contrast Gavrylyuk is explosively intense in No 5, and tells you also that No 8 is a place of bittersweet dreaming. Time and again he returns you to a period when Russian-trained pianists (and not only pianists) were dedicated exclusively to their art – to an endlessly evolving and developing journey (for Ashkenazy, a spiritual quest). Difficult, too, not to add that such manifest devotion must have prompted members of his wildly applauding American audience to wonder why a country with relatively limitless funds and facilities has created so few pianists of true international calibre in the past few decades. Virtually every pianist of note, whether male or female, comes from elsewhere.

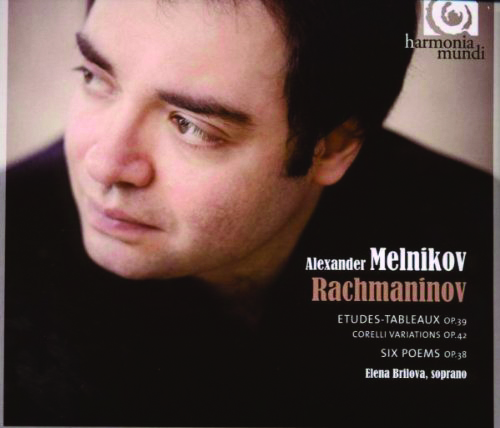

Alexander Melnikov shows himself to be a pianistic wizard, though one who never plays for effect or according to an external criterion (unlike Horowitz). For all his formidable mastery he never uses Rachmaninov as a springboard for excess. Greatly admired by Richter during his early career, he is a vitally enterprising pianist delighting in historic as well as modern performance. His collaboration with Andreas Staier and Alexei Lubimov, his recordings of Beethoven’s complete violin and cello sonatas and his desire to invite comparison between the preludes and fugues of Bach and Shostakovich perhaps give a clue as to the sheer quality of his Op 39 études. His storming journey through No 1 sets even the most sanguine listener’s blood racing, and here his command is so engulfing that he can allow himself a heart-stopping freedom and imaginative scope. What grandeur, too, in No 5, alive in his hands with a brooding and explosive menace. Intriguingly, and unlike Ashkenazy and Gavrylyuk, he finds a Mephistophelian glint in the outwardly playful measures that end No 8.

Crowning glory

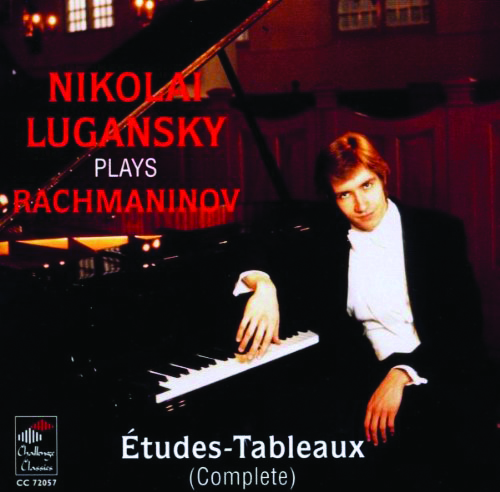

And yet, if I was to name the most trailblazing and meteoric performer of all it would have to be Nikolai Lugansky. A pianist who has sometimes shrouded his mastery in detachment, he is here at his most audacious, willing to step outside convention and declaim Rachmaninov’s glory to the heavens. There is nothing reserved in what is surely the most freely expressive, personal and, at the climax, seething performance on record of No 2. No 3 is of a shot-from-guns virtuosity that makes you cry out like Miranda in The Tempest: ‘If by your art, my dearest father, you have put the wild waters in this roar, allay them.’ There is nothing of a temporarily lighthearted oasis in No 4. Here, unlike Ashkenazy and Gavrylyuk, he is far from amiable, making you hear in his pace and urgency ‘time’s winged chariot hurrying near’. Again, there is to be no sentimental indulgence or malingering in No 8 but an impetus and momentum that would surely have caught the composer’s admiration. Rachmaninov himself was, after all, the least sentimental pianist in his own music.

Lugansky’s teacher and mentor Tatiana Nikolayeva declared her pupil ‘the next one’. She may well have been right, particularly when you hear playing of such an authentic, all-Russian vintage. Lugansky, and to an only slightly lesser extent Melnikov, are pianists who could surely exclaim, as did Claudio Arrau before them, ‘When I play I am in ecstasy; that is what I live for.’

Top choice

Nikolai Lugansky

(Challenge Classics)

In his Op 39 Lugansky trumps all aces with playing far remote from his occasional detachment. Indeed, his performance blazes with a demonic force, purging all possible sentimentality while telling you in every bar of Rachmaninov’s uniquely Russian flavour and stature.

Polymathic choice

Alexander Melnikov

(Harmonia Mundi)

Melnikov’s interest in historic as well as modern performance traditions and his participation in duos and chamber-music ensembles give his Rachmaninov an added richness, colour and drama. And his playing is as masterly as it is concentrated.

Young-star choice

Alexander Gavrylyuk

(VAI DVD)

The charismatic Gavrylyuk, possessor of immense technical resource, makes Rachmaninov the centre of this wide-ranging recital. With infectious brio and insight, he rises to the challenge of fluently communicating emotion to his audience.

Formidable choice

Vladimir Ashkenazy

(Decca London)

Formidably in command of even the most daunting technical challenge and remembering his Russian roots throughout, Ashkenazy can be more intimidating than affectionate in Op 39. But his authority is never in doubt.

Date / Artists / Record company (review date)

1945/75 Horowitz (excs) / RCA (70 discs) 88697 57500-2

1970 Van Cliburn (excs) / RCA (28 discs) 88765 40723-2

1971 Collard* / EMI 586134-2; 648345-2

1971 Ogdon* / EMI 704637-2; Testament SBT1295

1983 Shelley / Hyperion CDH55403 (8/88R)

1984 Richter (excs) / Praga DSD350 083

1985 Ovchinnikov* / EMI 232282-2; Olympia MKM145

1985/86 Ashkenazy* / Decca London 455 234-2LC6; Decca 478 6348DC11; (32 discs) 478 6765DB32

1988 Kissin (excs) / RCA RCA RD87982; Sony 88697 30110-2 (3/89)

1989 Biret* / Naxos 8 550347

1992 Lugansky* / Challenge Classics CC72057 (1/95R)

1994 Angelich* / Harmonia Mundi HMA195 1547

1995 Lill* / Nimbus NI5439; NI1786; NI1736

1996 Snyder / Bridge BRIDGE9347

1999 Kempf / BIS BIS-CD1042

2006 Hayroudinoff* / Chandos CHAN10391 (2/07)

2007 Gavrylyuk / VAI DVDVAI4433

2007 Paterson-Olenich / Prometheus Editions EDITION007 (9/09)

2008 Melnikov / Harmonia Mundi DHMC901978 (4/08)

2012 Cousin* / Somm SOMM0136

2012 Shybayeva* / Etcetera KTC1450

2013 Pizarro / Odradek ODRCD315 (1/15)

*coupled with Etudes-tableaux, Op 33

This article originally appeared in the July 2015 issue of Gramophone