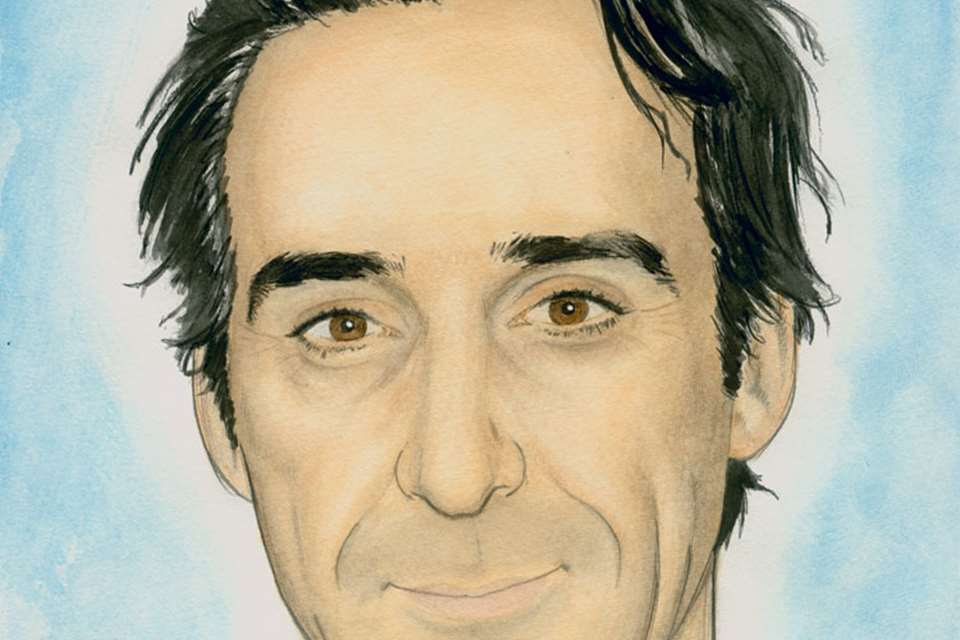

Stewart Copeland | My Music: ‘You must open your mind – and listening to eclectic music helps me do that’

Wednesday, May 5, 2021

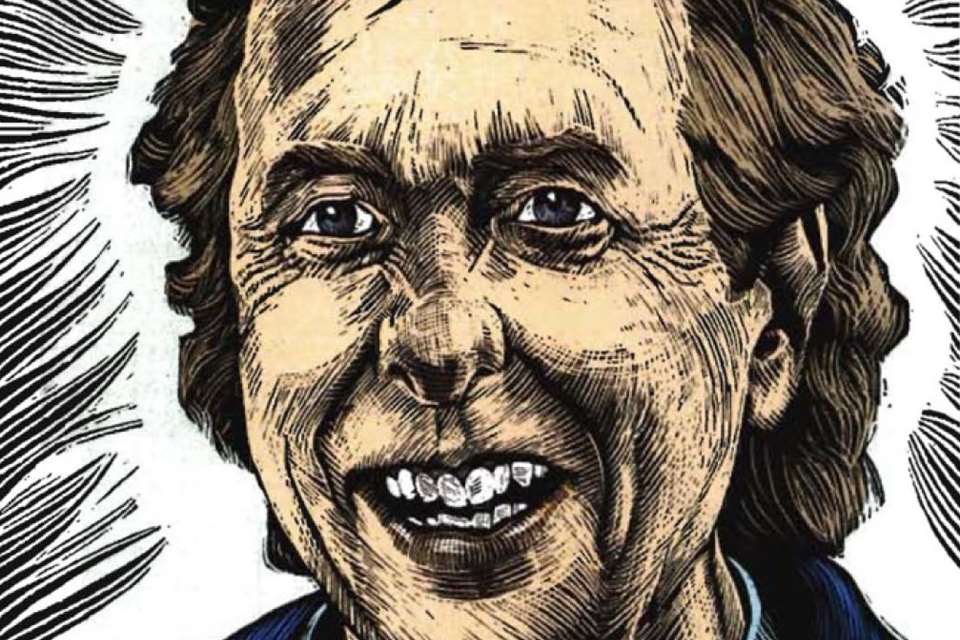

The co-founder and drummer of The Police on taming the ‘complicated beast’ that is the orchestra

![[Illustration: Philip Bannister]](/media/217828/stewart-copeland.jpg?&width=780&quality=60)

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter