Jed Distler's Cliburn Blog No 16: Alexei Sultanov reconsidered

Jed Distler

Friday, June 6, 2025

On a performance-free day of this year's Cliburn competition, Jed Distler reflects on the tumultuous, short life of a previous winner: Alexei Sultanov

On this performance-free day in Fort Worth, I’m reflecting on an upcoming milestone: the 20th anniversary of Alexei Sultanov’s death in his Fort Worth home on June 20, 2005, at the age of 35. His health had been considerably impaired after suffering a series of debilitating strokes in 2001. By then his career had pretty much spent itself out, merely 12 years after his meteoric rise to fame as 1989’s Cliburn Gold Medalist.

The 19-year-old Russian pianist’s Cliburn victory caused quite a stir. Joseph Horowitz’s book The Ivory Trade presented a play-by-play account of the 1989 contest, from initial selection of candidates to the concluding announcement of winners and everything in between. Sultanov’s daredevil style both excited and polarised listeners and critics alike, as well as jury members. György Sándor told Philadelphia Inquirer interviewer Lesley Valdes that Sultanov’s victory was ‘a tremendous scandal’. But Abbey Simon called Sultanov ‘a fearless, independent player’. 1962 Cliburn Gold Medalist and jury member Ralph Votapek offered a more balanced assessment: ‘His style works because he’s not dishonest. He sometimes does outlandish things, but I personally don’t think we could have gone any other way. He’s not a flash in the pan.’

But was he? Would Sultanov’s sudden stardom stay the course, or crash and burn?

A maelstrom of press events, television appearances and concert dates quickly engulfed the pianist. His youthful bravado and limited English made him an easy target, with talk show hosts treating him as a figure of fun. Sultanov’s recitals and recordings came in for criticism. Reviewing his 1990 Carnegie Hall debut, Donal Henehan in the New York Times described Sultanov as ‘a well-schooled young artist struggling to find something interesting to say’. Gramophone’s David Fanning disparaged Sultanov’s ‘gladiatorial’ approach to certain works, calling his recording of Rachmaninov’s Piano Sonata No 2 ‘a smash-and-grab account, an aggressively lit portrait of the piece rather than something experienced from within’ (8/93). By the mid-1990s, Sultanov’s increasing reputation for unreliable, diva-like behaviour began to catch up with him. He managed to make a comeback by entering the 1995 International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw. Archival recordings reveal that Sultanov was back on form, exciting as ever, and maturing. No first prize was given, but the jury awarded a shared second prize between Sultanov and the French pianist Philippe Giusiano. To Sultanov, this was not a success, but an outrage.

The 1997 Cliburn’s opening ceremony included speeches to patrons and donors by Cliburn executives, several Gold Medal laureates and Van Cliburn himself. Cliburn’s associate Susan Tilley asked Sultanov to say a few words. Noticeably inebriated, Sultanov took the microphone and delivered a rambling rant against the Cliburn organisation, calling the competition a circus, and declaring that there were three supreme beings in the classical music world: Van Cliburn, Vladimir Horowitz and himself. Consequently, Sultanov was banned from all future Cliburn events, and Columbia Artists management ended their seven-year association with the pianist. The following year Sultanov entered the International Tchaikovsky Competition, in a last-ditch attempt to restore his former glory. Despite positive audience response and some genuinely impressive performances that included an ovation-earning Prokofiev Sonata No 7, Sultanov failed to make the final cut.

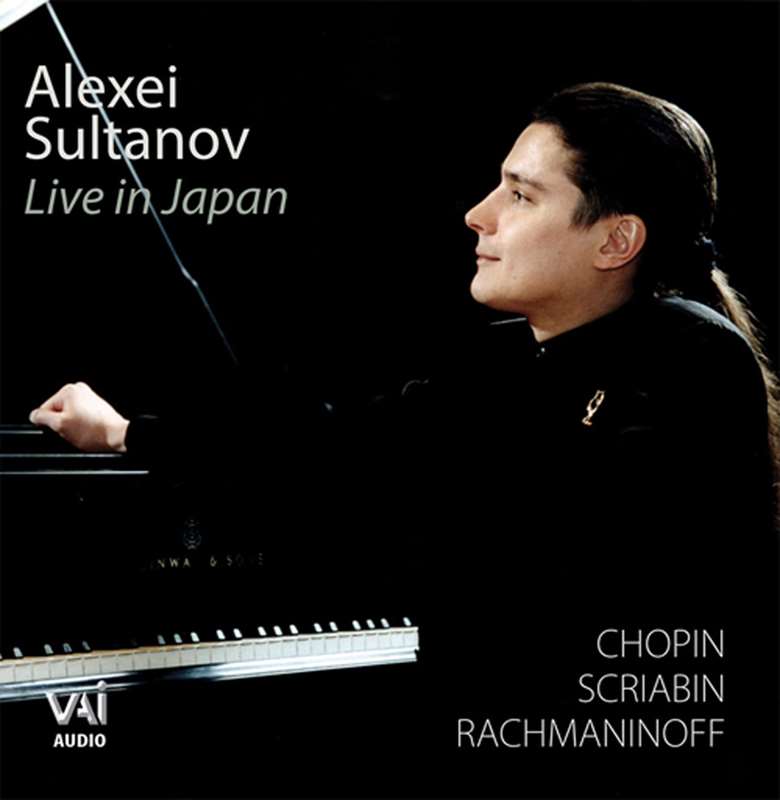

If Sultanov never quite acquired legendary status on the level of other tragically short-lived Cliburn participants like Youri Egorov and Steven de Groote, his meteoric career still holds fascination. TCU Press has recently published JW Wilson’s biography Final Encore: The Life, Music and Tragedy of Alexei Sultanov. And, of course, we have the recordings. I recommend a two-CD release containing exciting, occasionally infuriating yet always ear-catching live 1996 performances in Japan of Chopin’s Sonata No 3, Rachmaninov’s Sonata No 2 and Scriabin’s Sonata No 5 (VAI 1266-2). Here Sultanov operates at full capacity, and knows exactly what he wants to say, and how to say it. That in itself is no small achievement.