Alleluias: a specialist's guide

Peter Quantrill

Monday, April 10, 2017

For many people, the term ‘alleluia’ brings to mind the eponymous Handel chorus, but, as Peter Quantrill argues, there are many and varied examples of the genre through the ages and into the 21st century

There will probably, in the anglophone world at least, only ever be one Alleluia (or Hallelujah) Chorus in the popular imagination. But the word has spurred composers’ imaginations for well over five centuries. Deriving from a Hebrew phrase meaning ‘Praise Yahweh, you people’, whether spelt alleluia, alleluja or hallelujah, the word has indicated an exclamation of praise or thanksgiving ever since the fourth-century codification of early Christian rites.

The last of the Psalms of David, No 150, inevitably concludes with an alleluia, but, as Igor Stravinsky showed when setting that text as the final movement of his Symphony of Psalms, alleluias need not always be loud. Most of the composers cited opposite have not contented themselves with straightforward exaltation, but sought to create a mood that’s out of the ordinary: one of awe, wonder, even fear and trembling in the presence of something immanent and unknowable. The significance of ‘alleluia’ may now be as generic, yet as characteristic of its religion, as the Muslim ‘inshallah’, but it retains a specific liturgical function within daily worship and takes on particular relevance for feasts of joy and celebration, in particular Easter.

Several composers have turned to the Alleluiatic Sequence, an 10th-century poem that, like the Benedicite, lists the parts of the natural universe offering their own contribution to God’s glory: ‘The planets glitt’ring on their heavenly way, / The shining constellations, join, and say, / Alleluia[…] Thou jubilant abyss of ocean, cry, / Ye tracts of earth and continents, reply, / Alleluia.’ These couplets, two of the poem’s more splendid examples, come from a translation of the poem by JM Neale (who also wrote the words to ‘Good King Wenceslas’), which, published as ‘The Strain Upraise’ in 1854, became a text for hymns and anthems by SS Wesley, New York organist and composer Dudley Buck, and Sir Arthur Sullivan (see opposite). Using a modern translation, Julian Anderson set the sequence in 2007 for the reopening of the Royal Festival Hall in London. His Alleluia confirms that the word and the concept may still bring inspiration to composers seeking to celebrate. Alleluia!

Byrd Haec dies

The Cardinall’s Musick / Andrew Carwood

Hyperion (4/10)

‘This is the day the Lord has made’ is a joyful Easter anthem from Byrd’s Cantiones sacrae of 1591. The rhythm is the thing: Byrd works with the word but against the bar-line no less ingeniously than Stravinsky did three centuries later in the Symphony of Psalms. The anthem springs from its hemiola cries of ‘exsultemus’ into ‘et laetemur’ syncopations, before leaping into an alleluia sequence of steadily increasing contrapuntal intricacy, skating on off-beat entries.

Weelkes Alleluia, I heard a voice

Choir of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge / David Skinner

Obsidian (7/12)

Dating from around a decade later than Haec dies, this is Weelkes at his most relentless: a five-part anthem of wide-ranging but often mercilessly high-lying tessitura, and a textural turbulence that makes Byrd sound polite by comparison. The word itself takes on a hectoring intensity from the basses’ opening proclamation, intensified by outrageous false relations and capped by the trebles’ climactic leap to a top B.

Thompson Alleluia

Handel and Haydn Society Chorus / Grant Llewellyn

Avie (6/04)

Randall Thompson wrote this anthem in just five days in July 1940 at the request of Serge Koussevitzky, who would have known a hit when he saw one. Although it was commissioned for the opening of the Berkshire Music Center, Tanglewood (and has since opened every summer festival there), Alleluia has a subdued opening and restrained close, reflecting its wartime context. For a more spirited example of Thompson’s mock Palestrina, try ‘O fons bandusiae’.

Gubaidulina Alleluia

Danish National Radio Choir and Symphony Orchestra / Dmitri Kitajenko

Chandos

This 35-minute cantata in seven sections, written by Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina (b1931) in 1990, works through many of the expressive possibilities of the word ‘alleluia’ – like an actor trying out a line. It’s fearful, whispered and tentative at first, before solo voices begin to assert the idea more confidently in the con spirito third section of the work.

Sullivan The Strain Upraise

Choir of Keble College, Oxford / Mark Laflin

Priory Records

Plainchant meets prime Victoriana via Anglican psalm chant in this setting of JM Neale’s Alleluiatic Sequence translation. The steam of suet pudding rises from antiphonal proclamations, but there’s a foretaste of Iolanthe’s chorus of fellow Peris in ‘They through the fields of Paradise that roam’: Sullivan was just 26 when he wrote it in 1868 for Novello’s Supplemental Hymn and Tune Book (published in 1869), his first collaboration with WS Gilbert still three years away.

Schmidt Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln

Soloists; Wiener Singverein; North Austrian Tonkünstler Orchestra / Kristjan Järvi

Chandos (6/08)

For sheer force, not even Handel rivals this Hallelujah Chorus at the climax of Schmidt’s Revelation-texted oratorio. Its context, in which the end of things is foretold (in 1935-7) with bizarre and appalling imagery, lends the chorus a sinister, made-to-order power, stirred by a huge bass ostinato. It began life seven years earlier as an organ-only prelude with matching, Gothically imposing fugue.

Mozart Exsultate, jubilate

Michael Maniaci male sop Boston Baroque / Martin Pearlman

Telarc

Like Bach’s BWV51 from half a century earlier, this cantata was written for a high-voiced singer who happened to be in town, and whose unusual skill and range could be displayed with a final, two-octave alleluia. Bach’s soprano is now unknown to us, but the 17-year-old Mozart wrote for the castrato Venanzio Rauzzini. Modern equivalents are understandably hard to find, which makes Maniaci’s high-wire act all the more absorbing.

Messiaen Alléluias sereins d’une âme qui désire le ciel

LSO / Leopold Stokowski

Cala (1/00)

Part Gregorian chant, part Indian rhythm, part Stravinskian whole-tone harmony, wholly Messiaen. Composed at the age of 24, L’Ascension is the composer’s boldest orchestral work yet – ‘Alleluias sereins’ its twinkling second movement – and the nearest he came to reflecting the hum of jazz-age Paris, even in the organ rewrite of the following year. The orchestral original is a tawdry, guilty pleasure, especially with the LSO in full Hollywood mode under Stokowski.

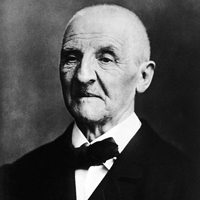

Bruckner Psalm 146

Soloists; Hans Sachs Choir; Nuremberg SO / Wolfgang Riedelbauch

Klassic Haus

Dating from Bruckner’s early thirties, this six-part hymn of praise for soloists, double chorus and orchestra is remarkable for its contrapuntal sophistication, culminating in a lengthy Alleluia fugue that for invention and pacing even puts to shame the ‘Cum sancto spiritu’ fugues of Schubert’s late Masses which Bruckner loved and studied. This is, surprisingly, the sole recording (only available at klassichaus.us).

Handel Hallelujah Chorus

RPO and Chorus / Thomas Beecham

RCA (5/60)

The library of Handelian choruses of praise contains examples more extravagant (‘Praise the Lord’ from Solomon) and more intricate (‘Thy right Hand, O Lord’ from Israel in Egypt), but the enduring success of the Hallelujah Chorus may partly be down to its relative flexibility and simplicity. The Sixteen’s first recording for Hyperion has a vitality no less infectious for being sung and played by fewer than the ‘forty voices and fifty instruments’ heard at a typical early performance in Oxford in 1749. However, for proof that Handel was, in the words of the 19th-century commentator Edward Fitzgerald, ‘a good old Pagan at heart’, Sir Thomas Beecham’s 1959 recording is impossible to ignore, less for Leonard Salzedo’s souped-up instrumentation than for Beecham’s unsolemn approach: light on its feet, charged with evangelical zeal.