Reputations: Montserrat Caballé

Gramophone

Saturday, October 6, 2018

The soprano who had it all: charisma, technique and sublimity, who has died at the age of 85

This article originally appeared in the October 2003 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing to Gramophone, please visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe

In 1980 Renata Tebaldi was asked by Lanfranco Rasponi what she thought of the state of singing. Her answer was unequivocal: there is just one prima donna left Montserrat Caballé. And in the same year Magda Olivero, the last of the hell-for-leather verismo sopranos and no mean diva herself, opined that 'we singers should get down on our knees and thank God for a voice like Caballé's'. These words prefigure a leitmotif that runs throughout Rasponi's book (The Last Prima Donnas; Alfred A Knopf: 1975) in which he interviews many of the great divas of the recording era: no matter how lamentable these monstres sacres believe the state of singing has become since they themselves retired from the stage, Caballé is usually cited as an exception to the general decline. So just how special is she?

To start with, her versatility: no diva in memory has sung such an all-encompassing amount of the soprano repertory, progressing through virtually the entire range of Italian light lyric, lirico-spinto and dramatic roles, including all the pinnacles of the bel canto, Verdi and verismo repertories, whilst simultaneously being a remarkable interpreter of Salome, Sieglinde and Isolde.

Consider, for example, the year 1979. Caballé 's stage roles, in order of singing, comprised: Maria Stuarda, Tosca, Leonora (in Forza), Elisabeth de Valois, Mina (in Aroldo), Salome, Norma, Elizabeth I (in Roberto Devereux), Gioconda, Turandot and Maddalena (in Andrea Chenier). And in between the Salomes and Normas, she recorded, back-to-back for EMI, Elvira in I Puritani and Santuzza in Cavalleria rusticana, both under Riccardo Muti. On paper, it looks absolutely ridiculous. And, of course, it has proved a hostage to critical fortune over the years, since it is a commonplace of Caballé criticism that she did too much, too often, too little prepared and in too many places. But it is noticeable that those who do the most head-shaking about these aspects of her career are likely to be the same people who comment most favourably when individual performances are brought forward for review.

Fortunately, almost all these 1979 assumptions survive, in the form of commercial recordings, pirates or telecasts. In the one-off Carnegie Hall concert of Aroldo recorded by CBS, her dramatic intensity blazes a trail through the score. Recorded a few weeks later, her Elvira on the EMI Puritani is an even more astonishing achievement, provoking Rodney Milnes' 'terrible confession, that if I want to listen to Norma or Puritani I listen to Caballé, not to Callas. It's the sound, the phrasing, the incredible musicianship.' Yet within days, she sets down as dark and distraught a Santuzza as has been committed to disc, before singing a dream Gioconda in Geneva (with Carreras), arguably even finer than the studio recording she made for Decca the next year. All this in her 25th year of professional activity. The woman was - and remains - a phenomenon.

The background is by now well known. Born into a family down on its luck with the Spanish Civil War looming, she knew genuine hardship as a child. The only ray of light was the time spent studying at the Conservatorio del Liceo in Barcelona. Recalling her voice teacher there, Eugenia Kemmeny, Caballé still smiles at the memory of the entire year her class spent singing only scales and engaging in 'respiratory gymnastics'. But she is perfectly aware that these provided the secure foundations of a technique that has lasted fully 50 years. The prodigious breath control that underpins her long phrasing, the muscular relaxation that allows her trademark pianissimi, the awesome - to some, notorious - ability to sight-read, are all skills she developed at the Conservatorio.

Given her level of technical assurance, it is strange that Caballé's earliest years of professional activity were so difficult. For a woman who became an 'overnight sensation' in 1965, she had spent the preceding decade in provincial obscurity, first in Basel and then in Bremen, scraping a living. Only back in Barcelona and with her marriage to Bernabe Marti in 1964 does a real sense emerge of the artist and the woman coming into her own.

The sensational Lucrezia Borgia in New York - which gave rise to the front page headline in the New York Times 'Callas + Tebaldi = Caballé' - was not a planned event. Caballé was simply replacing a pregnant Marilyn Horne, and moreover singing repertory with which she was not remotely associated at the time. But this is exactly the kind of unexpected occurrence or one-off event that brought out the very best that she had to offer. Like a number of truly great performers, Caballe did not respond well to routine and repetition, being happiest in lone concert performances or short runs. Not for her the calculated presentation of identical fare night in, night out. During a run of Tosca in Nice the stagehands took bets as to which of the numerous doors and floor-length windows of the Palazzo Farnese she would choose to exit, having killed Scarpia. They all lost money.

In 1970 she became well acquainted with Maria Callas, who was by then living in semi-seclusion in Paris. Although they were temperamentally poles apart, at a musical level the two women connected. Certainly Callas seems to have thought so: just days before her death in 1977 she gave her last interview to Philippe Caloni and, when asked if she considered she had any successors, stated 'Only Caballé'. One wonders what the Greek diva specifically had in mind. By that time she had seen Caballé triumph in the role of Norma and had even gone so far as to send the Spanish soprano the earrings she had been given by Visconti on the occasion of her first La Scala Normas in the 1950s. Evidently she believed the torch was being passed on. Yet few people think to link Callas and Caballé in terms of dramatic effectiveness, not least because Caballé has had to contend with a body that won't obey her wishes (owing to a malfunctioning hypothalamus, the body's main regulatory hormonal gland).

What really links the two divas is musical instinct at the profoundest level: the ability to transform what Richard Strauss referred to as 'bugs and fleas' - the notes of the score - into expressions of pure emotional drama. And one has only to see the performance Caballé gives in the live Norma from Orange, now widely available, to realise what a committed and uncompromising theatrical animal she could be. According to John Steane (3/03): 'On a wind-swept, genius-driven night in 1974, they had greatness itself... the role is sung and acted with such well-founded assurance that for once it fulfils its own legend, the embodiment of musical-dramatic sublimity in 19th-century opera.'

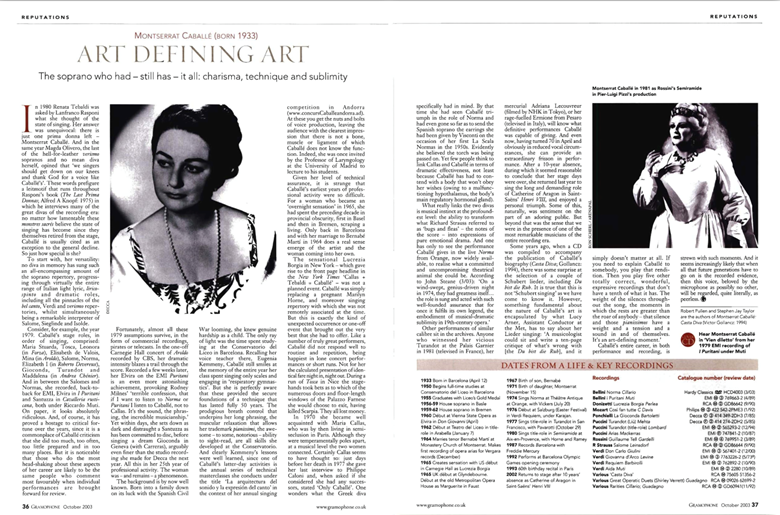

Other performances of similar calibre sit in the archives. Anyone who witnessed her vicious Turandot at the Palais Garnier in 1981 (televised in France), her mercurial Adriana Lecouvreur (filmed by NHK in Tokyo), or her rage-fuelled Ermione from Pesaro (televised in Italy), will know what definitive performances Caballé was capable of giving. And even now, having turned 70 in April and obviously in reduced vocal circumstances, she can provide an extraordinary frisson in performance. After a 10-year absence, during which it seemed reasonable to conclude that her stage days were over, she returned last year to sing the long and demanding role of Catherine of Aragon in Saint-Saens' Henri VIII, and enjoyed a personal triumph. Some of this, naturally, was sentiment on the part of an adoring public. But beyond that was the sense that we were in the presence of one of the most remarkable musicians of the entire recording era.

Some years ago, when a CD was compiled to accompany the publication of Caballé's biography (Casta Diva; Gollancz: 1994), there was some surprise at the selection of a couple of Schubert Lieder, including Du bist die Ruh. It is true that this is not 'Schubert-singing' as we have come to know it. However, something fundamental about the nature of Caballé's art is encapsulated by what Lucy Arner, Assistant Conductor at the Met, has to say about her Lieder singing: 'A musicologist could sit and write a ten-page critique of what's wrong with [the Du bist die Ruh], and it simply doesn't matter at all. If you need to explain Caballé to somebody, you play that rendition. Then you play five other totally correct, wonderful, expressive recordings that don't have a tenth of what it has. The weight of the silences throughout the song, the moments in which the rests are greater than the roar of anybody - that silence and those pianissimos have a weight and a tension and a sound in and of themselves. It's an art-defining moment.'

Caballé's entire career, in both performance and recording, is strewn with such moments. And it seems increasingly likely that when all that future generations have to go on is the recorded evidence, then this voice, beloved by the microphone as possibly no other, will be regarded, quite literally, as peerless.

Robert Pullen and Stephen J Taylor