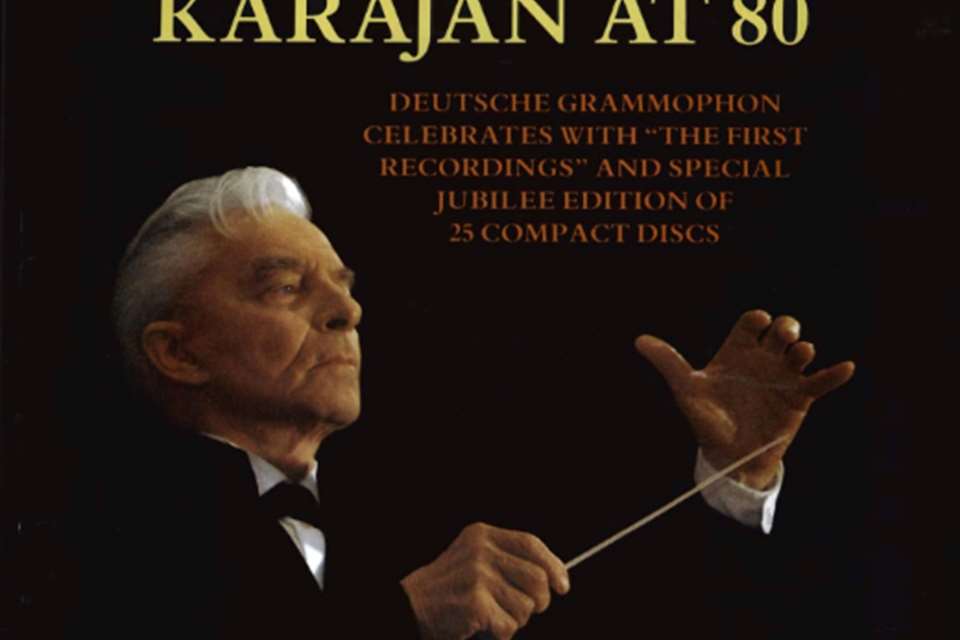

Classics Reconsidered: Karajan’s 1981 recording of Nielsen’s Fourth Symphony

Friday, May 16, 2025

Andrew Farach-Colton and Andrew Mellor return to Karajan’s 1981 recording of Nielsen’s Fourth Symphony, an outlier in the conductor’s extensive discography

The original review

Nielsen Symphony No 4, ‘The Inextinguishable’

Berlin PO / Herbert von Karajan (DG)

With Igor Markevitch’s 1967 record now deleted, the only really satisfactory account of this symphony is Ole Schmidt’s (LSO; Unicorn-Kanchana). Zubin Mehta’s (Los Angeles Philharmonic; Decca) is superbly recorded but is ruthlessly efficient and remains obstinately earthbound. Sir Alexander Gibson’s (SNO; RCA) is much to be preferred but Schmidt’s has more character. Karajan has not yet recorded a Nielsen symphony, so that much interest attaches to the present release. To be frank, it seems to me by far the finest to have appeared since the pioneering issue by Launy Grøndahl (Danish State Radio Orchestra; HMV); the orchestral playing is altogether incomparable. Grøndahl brought a robust peasant fire to the first movement whereas Karajan is broader, more magisterial, and noble. Some may feel the A major blaze at the end of the exposition of the first movement almost self-consciously majestic. Personally, I find it magnificent.

The theme is beautifully shaped on its entry and elsewhere throughout the score, and the orchestra play as if they are enjoying this music. They respond with the freshness of new discovery. They attack the third movement with passionate intensity and bring a wonderful sense of mystery to its magical quieter sections, such as fig 54 in the finale, which I have never heard to better effect. In the Intermezzo, I can imagine some listeners wanting more direct, primary colours from the wind; they are so subtly blended that they convey an over-civilized impression, offering silk where plainer textures are normally what we are given. But what beautiful playing! The finale is altogether thrilling though I was a little puzzled by the dramatic pause at fig 61. Overall, this is a performance of such power and vision that it carries all before it. It is the best played and recorded Inextinguishable to date. Robert Layton (3/82)

Andrew Farach-Colton I’m fascinated by this 1981 recording, Karajan’s sole foray into Nielsen’s music (although, tellingly, it’s a work he never actually performed in public). When I first heard it many years ago, I found it utterly unidiomatic. Returning to it today, I feel much the same way, though I now find many admirable qualities as well. Still, I’m perplexed by Robert Layton’s wholehearted embrace of an interpretation that seems such an obvious outlier. Or am I simply being narrow-minded?

Andrew Mellor I don’t think you are. Unidiomatic is the word. Nielsen wanted to move music away from the ‘gravy and grease’ of the German tradition – a tradition (think Brahms) that Karajan and the BPO became synonymous with. So yes, it’s odd to read words like ‘magisterial’ and ‘noble’ in RL’s review – and so much reference to ‘beauty’ – when Nielsen was so clearly aiming for something else. But as for the ‘admirable qualities’, I agree to an extent – what do you have in mind?

AFC Listening to this recording with score in hand, I’d say Karajan is generally attentive to Nielsen’s directives. Did you notice how softly he has the Berliners playing in quiet passages? Take, for instance, the Poco allegretto, whose opening is marked ppp (this entire section hardly rises above mp, in fact). I don’t think any other version I’ve heard comes as close as this in conveying that hush – or perhaps it’s meant as a sense of physical or temporal distance (something faintly remembered or heard from afar?). Do you think this was aided by the engineers? And were you also bothered by the exaggerated dynamic range which requires continual adjustment of the volume?

AM Sometimes I notice knob twiddling – something is going on with the balance at bar 140 (first movement, 5'30"), with the timpani above those held string chords – but I am mostly OK with it, as Nielsen needs help with balance, whether it comes from a conductor or a sound engineer (violas need particular help). I take your point about a sense of distance. I think Karajan is best when the music is really churning; this is when the strength of his orchestral sections pays. A problem for me is the startling lack of energy in places, particularly at risoluto e giusto (bar 97, 3'38") and at pesante ma glorioso shortly afterwards (bar 121, 4'30"). This, for me, is where Karajan has misunderstood the music’s fundamental footing – and the title, Inextinguishable. Is that unfair?

AFC No, it’s not. I agree, actually, yet I can kind of see where Karajan is coming from, and that’s what fascinates me about this recording. The passages you mention are prime examples of him attempting to make sense of Nielsen’s markings. One could make a case that his hearty risoluto e giusto is ‘resolute and exact’ even if it’s much slower than we’re used to hearing. The trouble is that by holding back here as he does (and in a most Brucknerian way, I’d say) and then not quite accelerating back to Tempo I as instructed, the pesante ma glorioso that follows is too heavy – more ponderous than glorious. Do you hear a lot of Bruckner in this performance, too? I’m thinking also of the con fuoco at bar 215 (7'12").

AM That’s exactly right; you have to click back into the fundamental tempo to make the whole argument work. That said, if Bruckner’s shadow looms too large, it works better structurally than it does sonically, which leads to some thoughts on articulation. The jabbing woodwind at bar 603 in the Poco adagio (5'32") – and the same gesture in the strings 10 bars later (this is the agitato section) – surely need sharper articulation to conjure that sense that the music has been infected with malign forces. And yet it’s ironic, just as you say, that the glorioso elements fall flat. Another example are the horncalls in the finale at bar 835 (32'11"), which just don’t thrill enough. Is it a case that with Nielsen, as with Janá∂ek, sometimes a plush legacy orchestra – certainly one under Karajan – can all too easily sound too mahogany and aristocratic?

AFC Certainly. Yet I find Sir Charles Mackerras’s Janá∂ek with the VPO surprisingly compelling (he did have a close connection to that tradition, though). How do you feel about Karajan’s Sibelius? I know the BPO’s mahogany plushness is ‘wrong’ for a lean work like Symphony No 4, but he seems so intensely connected to the music’s spirit that it works, at least for me. With Nielsen, it’s a different story. In that agitato passage you mention, I think the issue is as much about a tempo that’s too slow as it is about articulation that’s smoothed over. Karajan makes it a lament, and I think that could be a viable reading if it made sense in the overall narrative – but it doesn’t. Do you find his interpretation disconcertingly episodic, too?

AM I’m glad you’ve mentioned Mackerras’s Janá∂ek because that has always been, for me, the exception to the rule, the mark of a conductor who knows how to channel a distinct idiom. As for Sibelius, I agree. In terms of surface noise rather than internal construction, Sibelius was often after something Brucknerian. Perhaps the problem is that Karajan conceives Nielsen as closer stylistically to Sibelius than he really is. Episodic? Certainly – surely connected to those tempos that don’t feel born of the fundamental tempo. But I also find the performance compartmentalised in terms of orchestral sections (Bruckner again!) – there’s the feeling of parts assembled together, rather than a single musical statement.

AFC I hadn’t thought as much about the orchestral sound being Brucknerian, but you’re spot on – there’s a sense of distinct orchestral sections, like organ registers. So, thinking about the Inextinguishable’s discography, do you think this work is simply more circumscribed than usual in terms of interpretative options? I just listened again to Gennady Rozhdestvensky (Chandos), though, who is also relatively spacious, and yet he sustains the narrative arc. There’s a lamenting character there, too, in that ‘malignant’ phrase you mentioned earlier, but I think it fits into the overall conception, which is more lyrical than most, at least as I hear it.

AM Sure, the score doesn’t give you much room to manoeuvre, but Nielsen wasn’t the best orchestrator and it does need balancing (you can tell Rozhdestvensky’s orchestra is far more at ease with the idiom than Karajan’s, for all its plushness). As for lyricism, I think the best recordings do combine that incendiary feeling with a breakaway, spacious lyricism – the essence of Nielsen, you could say, but a quality that is hard to come by. I have always admired Michael Schønwandt’s Danish radio recording for that, and more recently, Sakari Oramo in Stockholm. What did you make of Fabio Luisi’s 2023 Gramophone Award winner?

AFC I had a hunch Luisi’s recording would come up. Look, I think it’s gloriously played. In fact, it’s nearly as polished as Karajan’s account, although, of course, the Danish National SO is even more attuned to this music than Rozhdestvensky’s Stockholm band. I do think Luisi tends to create excitement through speed rather than by digging into the music. I need more grit and a greater sense of struggle, and while I admire the gravitas of his Poco adagio, his reading of the finale seems glib to me. A great performance sends chills down my spine and ends with me in tears, and Luisi’s doesn’t manage either of those. Schønwandt’s does, certainly, but then so does Jean Martinon’s Chicago recording, which is as propulsive as Luisi’s. What are your thoughts?

AM Martinon I have always liked. I take your point about Luisi, but to my ears, Herbert Blomstedt in San Francisco takes the biscuit in terms of creating excitement to the detriment of depth and churn (‘struggle’, to use your apt word). Luisi wouldn’t be in my top three (maybe top six), but I admire his contribution to the conversation in broad terms and, more specifically, his lyricism. I think the recording’s real triumph is the playing (as you say) and the recorded sound, which was a revelation to me – that combination of perspective and detail, which I suspect played a role in its big win. But for a composer who has for so long been ignored or misunderstood, how great that Nielsen was recognised as Recording of the Year – a reminder that in Karajan’s Germany, Nielsen was even less regarded. So, in conclusion, I guess, good on him for taking on the Inextinguishable!