Composing for Buster Keaton

Martin Cullingford

Friday, November 5, 2021

Carl Davis talks about writing scores for some of silent cinema's greatest creations

Buster Keaton's silent comedies - whether feature-length movies like The General and Steamboat Bill Jr, or shorts like One Week - are classics of cinema history. Carl Davis has dedicated a huge part of his career to creating and performing new scores for silent films, and highlights of those for Keaton's movies have now been remastered and released. Gramophone's Editor caught up with the composer to talk movies, music and Buster.

We all had our lockdown discoveries. Some took up cooking, yoga, a new instrument, a new language. For me, it was the silent movies of Buster Keaton, a remarkable catalogue of painstakingly planned and often extraordinarily funny films, full of scenes whose subtlety and style reward repeated viewings by unfurling greater depths of humour and humanity.

That Keaton’s characters, who through spirit or sheer persistence triumph in the face of life’s adversity or simply absurdity – or, if they fail, do so with a knowing nod of resignation that feels like vindication all the same – are so vividly memorable, is all the more impressive given that his trademark was never to smile. Like dialogue described in dance, or the eloquence in mute mime, or pictures painted in prose, Keaton communicated more with his ‘stone face’ than a thousand lesser performers could by employing the full facial armoury actors usually use. Meanwhile, his cinematography demonstrated a genius for guiding the eye and attention that brilliantly delivered both pictorial poetry and punchlines alike. And yet for all his visual virtuosity, the artform’s infancy sadly ensured that one crucial element remains both absent and elusive. For Buster Keaton’s films were, and are, silent.

They wouldn’t have been of course. The films would have been accompanied – literally – by live music. But, particularly in Keaton’s case, we’re not exactly sure what. And that is where Carl Davis comes in. An expert on silent cinema, the composer and conductor has carefully crafted a sound world for Keaton’s creations that captures their period and panache, and brings them alive for generations today – a century, remarkably, since they were made.

Buster Keaton, a genius of the silent comedy era, in The General

‘There's nothing more dreary than watching a silent movie in silence!’ Davis begins, as I ask him to distil the role he feels music plays in silent movies. But it comes as a surprise to discover that dispatching dreariness was not movie music’s initial aim. The origins of the film score, now so intrinsic to the artform, were somewhat more, at least partly, prosaic. ‘One of the first reasons music was introduced was because when showing the film publicly the projectors made so much noise that music was brought in to see if it could mask it,’ says Davis. ‘Sometimes sprocket holes were actually punched as the film went through – so it made a great din.’ But clatter conquered, it was soon discovered that ‘there was also a sense that the pictures were more effective if you had music, because music can set the scene. What kind of film is it? Is it a comedy, is it a tragedy, is it a romance? Where is it set? In one sense, in a silent film, the music is telling you the story – I’d say the nearest thing is Wagner, where the entire story is completely supported by a symphonic score which is giving you a lot of information that you don't see. And that is so with films today too, but of course in silent films you don't have dialogue, you don't have sound effects – except for what you choose to make in the pit, which is why you have a percussion section!’

Davis developed his interest in silent films – and first began writing scores for them – when working on a 13-part Thames Television series called Hollywood, by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, during the 1970s. ‘We spent a lot of time working on the music for it, involving a lot of research in libraries in New York, Washington, and Los Angeles.’ It also brought him into contact with people – somewhat elderly by then of course – who had been around in the genre’s golden days. ‘That was a kind of revelation,’ recalls Davis, ‘not only for me but for everybody, to discover the enormous range, and technical care, and the life of musicians working at the time, the orchestrators and arrangers, the musicians in the pit – it was quite commonplace to have musicians on the set who put the actors into the correct mood. It was a global industry, and these were all lives lived in that world, and very dependent on it.’ It was a world, however, that was to be silenced by sound. ‘That was a huge crisis for musicians, another story of an industry shifting, and people not being needed anymore. They didn't need musicians in the pit, they could show the film without them. That whole concept vanished and a lot of people were put out of work.’

The great directors, however, were completely aware of the place played by music. ‘They are very often quoted as saying that music is 60 or 70 per cent of the effect of the film,’ said Davis. ‘They expected it, and at best respected it. When Charlie Chaplin, in 1930, was finally able to make his first sound film, City Lights, he could control the sound 100 per cent by being able to record a score. But before that he, and others like DW Griffiths, had tried to very carefully control the music – certainly for premieres – or had engaged composers to write music, and these scores still exist. It was a very important part of the presentation of the film. ‘If you take the third giant of comedy, Harold Lloyd, there's usually a song written especially for his films, that's published and recorded for the gramophone. There's quite a library of Harold Lloyd songs - not that he wrote them, but there was an interest taken in them.’

And yet when it comes to Keaton, a director so meticulous about every other aspect of his films: silence, it seems.

‘The Keaton films are really naked, I couldn't find anything specifically relating to Buster,’ says Davis. ‘So it was up to me to invent my own Buster.’

Davis's score for The General draws on the songs of the Civil War

In explaining how he did that, Davis first returns us to those other two comic giants of the period, Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd. ‘They're very, very different creatures, and they rose to fame because of particular characteristics. We have Charlie as the gentleman tramp, that was his later description of himself – there's always a sense of politesse with Chaplin, you don't know much about him: where did he come from, did he have parents, how did he get into such a state? He's the outsider, and trying to get in for survival's sake. Lloyd is a creature of the 1920s, he's your average man, and he's trying to just get ahead in life, that's his aim: get ahead, make money, have status. He's yearning for success – whereas I'd say Chaplin is yearning to survive.

‘Then when we come to Keaton, the third member of the triumvirate, we have an enigma. His gimmick was a frozen face – he was called “old stone face”. He was impenetrable in his motivation, you don't know anything about him because it’s all concealed behind this sort of paralysis – except his eyes, which are very alive. So I decided that what motivated him was a sense of purpose, he always comes to life to do something – like drive the train in The General, or propose to the girl, or get out of proposing to the girl – otherwise he was completely still.’ So, Davis decided, ‘my role would be to help him. If he had a job to do, I'm doing that job with the score. I'm rescuing the girl, rescuing the train, doing a chore, putting up a house. I'm on his side musically.’

‘The first idea I had when I started doing clips of Keaton was to think of something that had a kind of mechanical aspect to it, and I was very taken with Scott Joplin rags, which are always instructed never to be played fast. It's a slow rag – um, cha, um, cha … undeviating – and this could be the ticking over of a mechanical clock in Keaton's mind, working like clockwork so to speak. And so I started writing Keaton rags for him.’

Listening to Davis’s scores, there’s a strong sense of a film’s period, one which sets the scene and strives to add appropriate colour to Keaton’s carefully created canvas of historic detail. ‘I operate starting from a sense of respect for the period the film was made,’ says Davis.

‘Chaplin and Lloyd were basically working in the historic present. If Lloyd made a film in 1925, it was 1925 on the screen. Whereas Keaton had a liking for moving through different historical periods.’ The General, made in 1926 and often cited as Keaton’s masterpiece, is set in the early years of the American civil war, the 1860s – indeed the film opens with the Civil War being announced. So, as he puts it, Davis ‘dived into the enormous number of patriotic songs that were composed at the time.’ This wasn’t, however, just to evoke the era. ‘The film being silent, and black and white, it was quite important to be able to differentiate between the North and the South. So I did this through songs, as each side had had their own songs. The North had their most significant song, very specifically about the incident used as the subject of the film, called Marching through Georgia – so that was the Northern side. And there's another one, The Bonnie Blue Flag, which is for the South. So you might help the audience to say “that's the North, that's the South”. In a way you're doing what military music usually does – which was to give you signals before the invention of walkie talkies!’

The songs become themes through which Davis tells the story, shaping them as the story, and our protagonist, progresses. As well as the martial music, Davis also borrows other sounds from the time to add orchestral colour. ‘It was the age when the harmonica had just been invented, so I used that, and also banjo – just these little things that help with the location.’

In Steamboat Bill Jnr, Carl Davis drew on jazz and the blues

Our Hospitality (1923) meanwhile, takes viewers back earlier still to the 1820s, which led Davis to ‘something more Schubertian – particularly as there's a funny moment when Buster decides to go fishing, and so I thought of The Trout of course, so there's a little quote from that!’ The fluvial theme continues later with references to Schubert’s river-based song Auf dem Wasser zu singen. ‘The whole score is inspired by chamber music. I decided I wouldn’t use percussion, and modelled it on one of these larger-scale chamber pieces, something like Schubert’s Octet - though in fact I use 18 players.’ Steamboat Bill Jr (1928) however, was set in its contemporary time, so there Davis created something, as he puts it, 'a little more jazzy and bluesy'.

But for all the setting of scene and era, Davis reminds us that the music still has to function as a film score, synchronized to the screen. ‘It’s got to fit, and it’s got to change when things change. And so you then start asking yourself what the content of the score is to be. So you create themes which are recognisable – we're back with Wagner now, in the world of leitmotifs, of significant themes which develop, just as they do in classical music from Haydn onwards: you state your theme, and then you start to work with it, depending on what the action is. Is he getting anxious, is he getting upset, is he happy, is he sad, where are we going with this scene, what's its outcome, what takes you to the next scene? You're writing with a very symphonic frame of mind, and you're developing themes depending on the action.’

As well as Schubert, the attentive ear might pick up moments of Mozart in the scores for two shorts, The Scarecrow (1920) and The High Sign (1921). Keaton adored mechanical devices, an obsession which finds its way into several films. In The Scarecrow there’s an extended sequence involving a house full of labour-saving devices and somewhat eccentric gadgetry. ‘The stove tips over and becomes a sink, utensils are passed back and forth… and so I thought that the plinky-plonk of the Papageno Papagena duet from The Magic Flute had a certain mechanical quality that would lend itself to the way all these things move around.’ The Magic Flute makes another appearance in The High Sign’s climatic sequence, when Keaton’s character is battling a group of gangsters in a house full of booby traps and obstacles – this time the Second Act music associated with Sarastro and the temple trials. Earlier in that score Wagner’s Valkyries briefly ride in too.

But as Davis points out, a musical borrowing needs to work both for those who get the reference, and on its own terms too. ‘The public today has a much greater exposure to music than the audiences of the early silent films, so I try to be very careful about what I borrow because I know that a portion of the audience will have an association with it. So if I quote from The Trout, it has to be effective on its own terms. It also has to be not that obvious, it has to be integrated into the score.’

Buster Keaton's The General is considered a classic of the cinema

But sometimes, for all the scope of a symphonic score, or the possibilities presented by a pit of players, for some scenes simplicity seems the only solution. ‘Sometimes Buster takes a routine to somewhere where it doesn't matter what the story is or what film he's in – he's just interested in the thing itself, the specific chore, which clouds out everything else.’

One of Keaton’s most memorable moments – a brilliant example of this – comes in Steamboat Bill Jr. Keaton’s character has arrived from East Coast academia to visit his father, the captain of a paddle boat, only to find him clearly horrified by his son’s eccentric style of dress – topped off, literally, by a beret. ‘So he drags him off to a haberdashery shop to buy a new hat,’ says Davis, picking up the story. ‘And there's a sequence, of three-and-a-half minutes, of Buster trying hats on. So as the routine started with a beret I’d thought I’d follow that line… beret, French music, accordion, a little chanson… We’d forget the orchestra, just as Keaton has forgotten everything too, except his interest in finding the hat which is just right. So we sent everyone out of the studio and just kept the accordion player, and I wrote this little French-style piece. And there Buster is, trying his hats on with this enormous intensity that he has: forget the film, forget everything else, we're trying on hats! A lot of Keaton films have those lift-out moments and you can isolate them – and so I tried to isolate this scene in this very focussed way too.’

For all Keaton’s spectacular stunts, this seemingly simple scene remains one of his finest: the interplay of protagonists, the impeccable pacing, the perfectly prepared visual punchline – and this genius of the genre’s frozen face as eloquent as ever.

And then our conversation concludes in a way that couldn’t be more appropriate. ‘You’re now going to hear my backing music,' Davis suddenly says, 'a full-scale military band marching past my house! Here they come!’ For a moment I fear too much immersion in Keaton’s sometimes surreal world has taken its toll, but I needn’t have worried. Davis lives in Windsor, and a military band does indeed process past his house, en route to the castle and back, twice a day, like clockwork. 'I can tell you, my writing for percussion has totally shifted!’ he laughs. ‘They’ll be back in half an hour for lunch. I always feel they play a little faster when they return because it’s lunchtime.’

A classic scene, gently subverted with a touch of affectionate humour: it’s a moment worthy of Keaton himself.

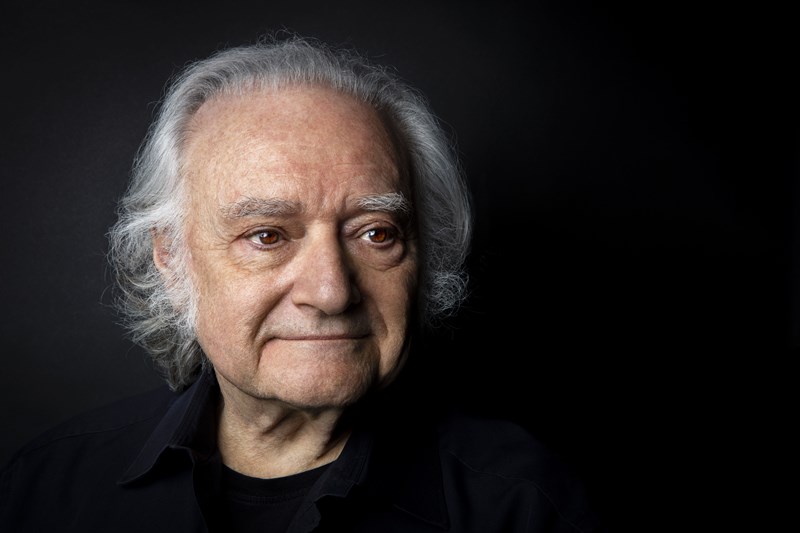

Carl Davis, whose new scores help bring Buster Keaton's classic films to life for audiences today (photo: Trevor Leighton)

'Buster Keaton - the Carl Davis Soundtracks', featuring highlights from the composer's scores, recorded by the Thames Silents Orchestra, the Chamber Orchestra of London and the Czech National Symphony Orchestra between 1984 and 2020, is available from November 5. Hear it below, via Apple Music.