Gramophone magazine: a history – the 1920s

James Jolly

Friday, January 5, 2024

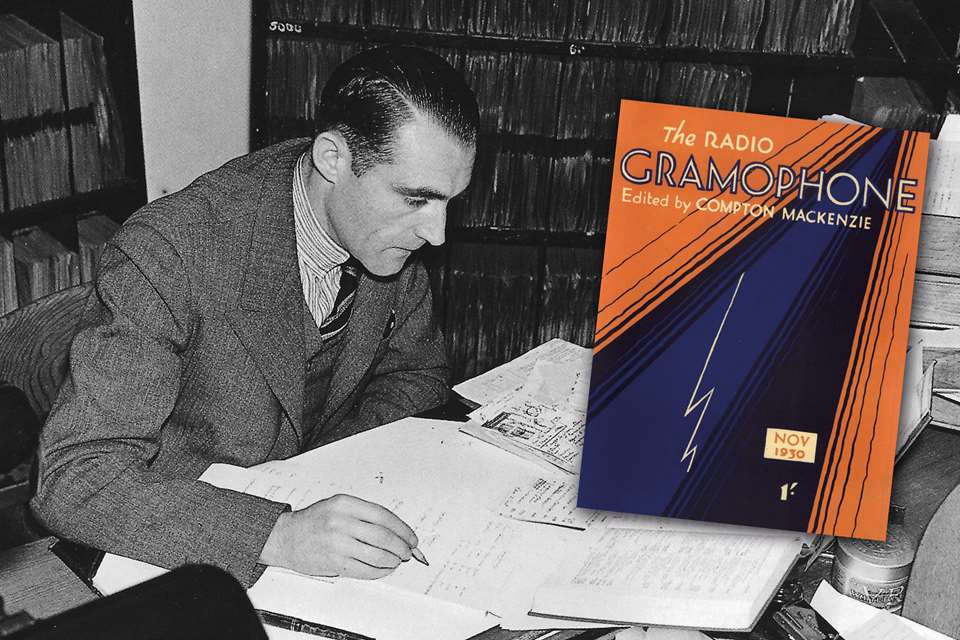

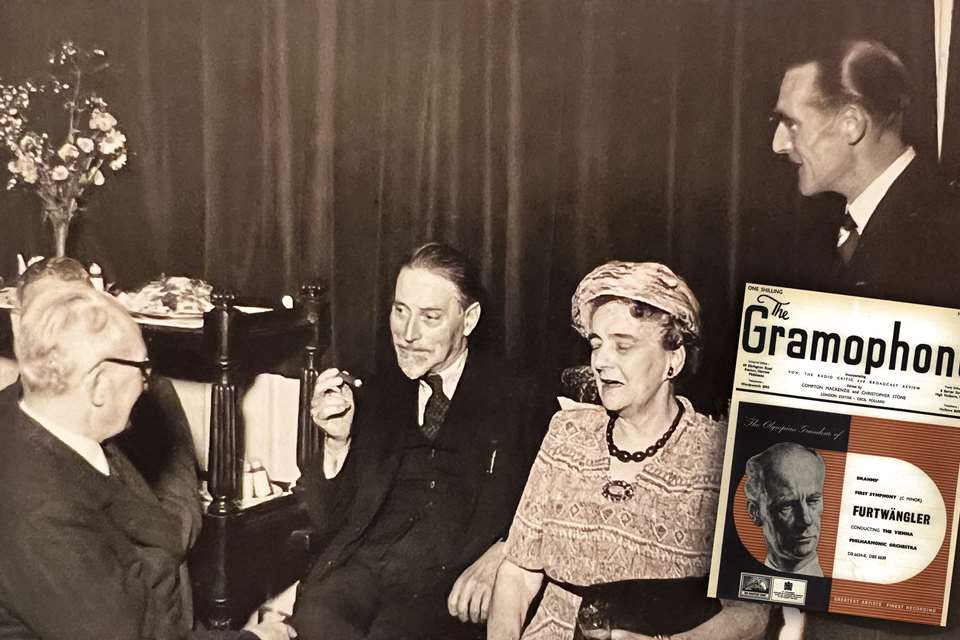

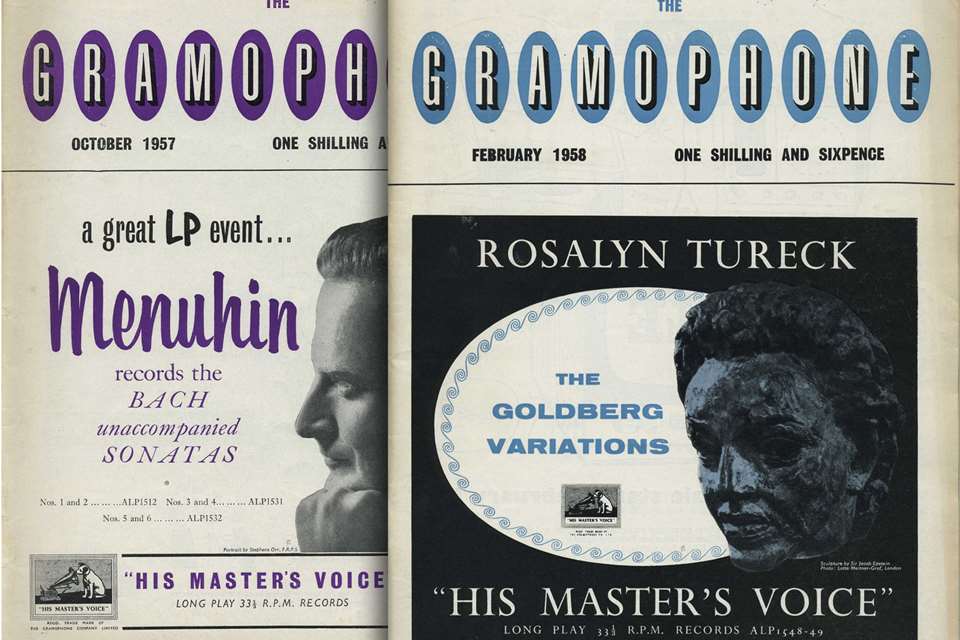

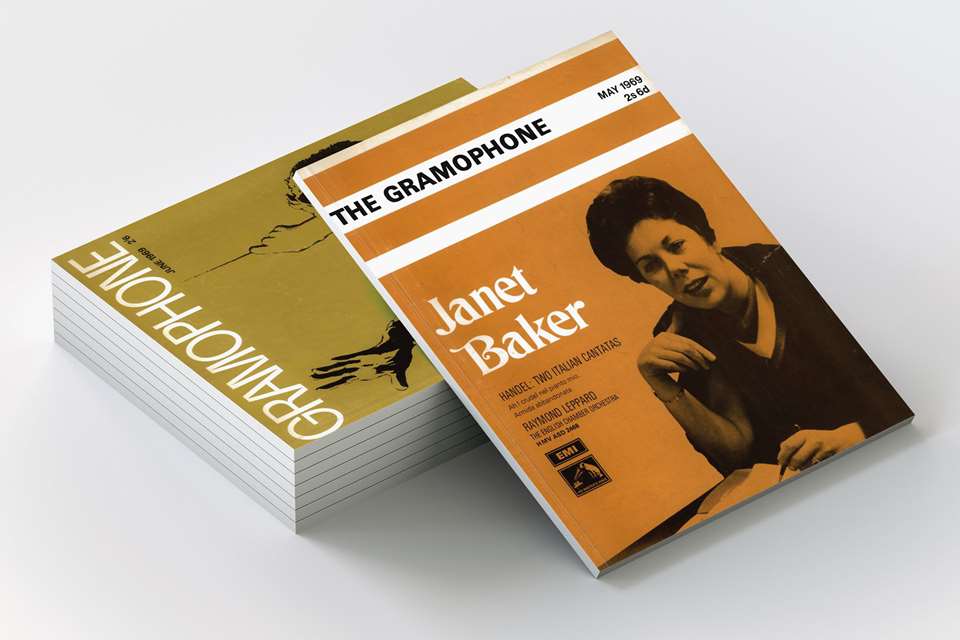

In 1923 Compton Mackenzie responded to music-lovers’ pleas for a new magazine about records and launched The Gramophone

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter