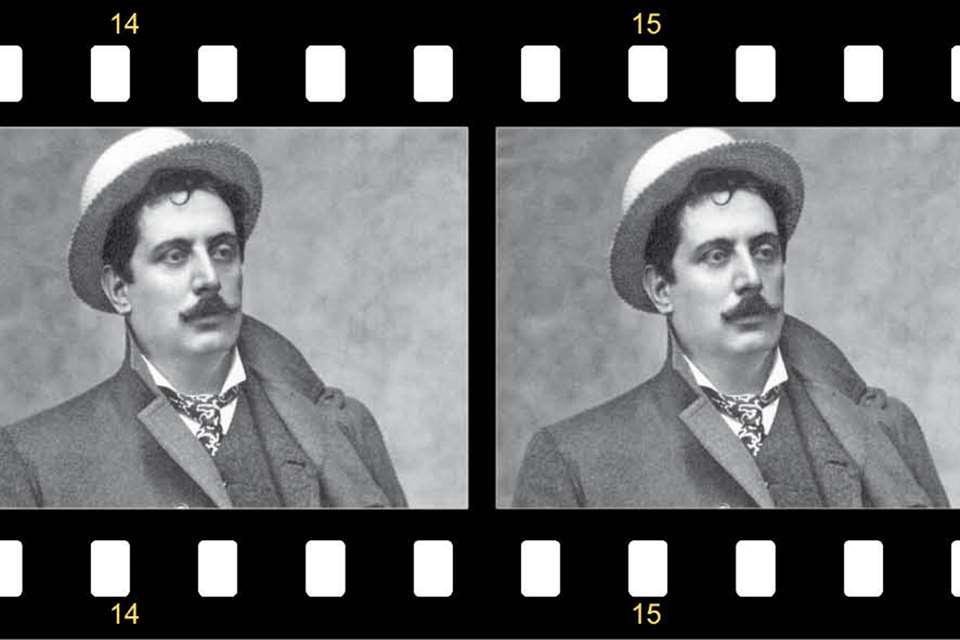

Puccini’s Turandot: the inside story of a major new studio recording

Neil Fisher

Monday, March 20, 2023

A major studio opera recording is rare nowadays, but add in Kaufmann, Radvanovsky and some unusual material and it has all the makings of something unique indeed. Neil Fisher visits Rome to sit in on Pappano’s ‘complete’ Turandot for Warner Classics

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter