Sir Georg Solti by Edward Greenfield (Gramophone, August 1981)

James McCarthy

Thursday, March 15, 2012

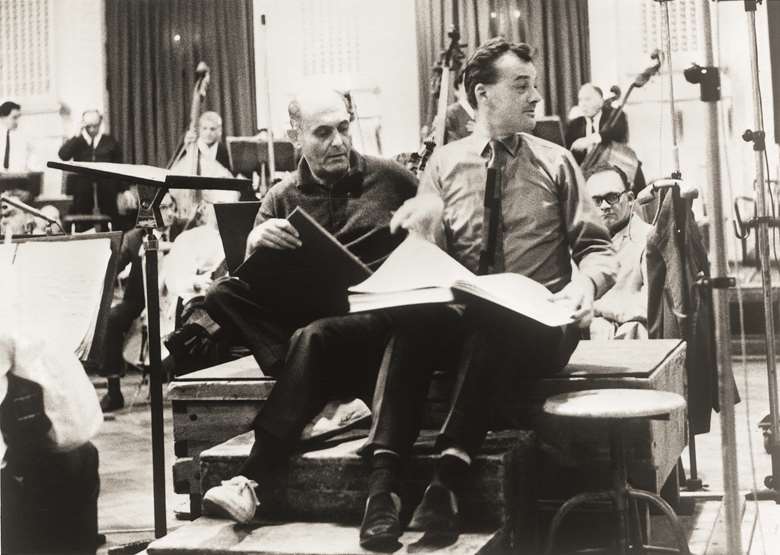

‘I’d buy the record just for that!’ said Sir Georg Solti in great glee. The scene was the control room (originally vestry) at Kingsway Hall. We had just heard the playback of the Countess’s first aria, ‘Porgi amor’, from Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro. Listening next to Sir Georg was the radiant soloist, even creamier in tone than one usually hears her on record, Kiri Te Kanawa. It seemed the culmination of a whole morning’s work on the latest complete recording of Figaro from Decca, but that was to underestimate the electrifying dynamo that is Sir Georg Solti. First there was a reservation to make about the introduction to ‘Porgi amor’, the tiniest of horn-fluffs. ‘We covered that on another take’ said the recording producer, Christopher Raeburn, reassuringly. ‘The same speed?’ asked Solti keenly. ‘if anything a fraction more fliessend [fluently]’ said Raeburn, knowing that that would fit. Sir Georg sat back, though only to work out what could be accomplished over the remaining 50 minutes of the session.

In all my experience of going to recording sessions over 25 years I cannot remember another span in which so much was done in so short a time, the pace of achievement exhilaratingly fast, the actual music-making relaxed as well as joyful. It made a total contrast with what I had witnessed at the equally impressive Mozart sessions on The Magic Flute for EMI that I had just attended in Munich. There with Bavarian Radio engineers calmly setting the pace and Bernard Haitink quietly authoritative, ever ready to listen, there was no feeling of urgency whatever, with the number of sessions allotted to the project twice as many as for this Figaro. The Decca schedule had the whole opera packed into an intensive 10 days with only one orchestral session possible each day: the orchestra (the London Philharmonic) had promptly at two o’clock to think of getting down to Glyndebourne, on alternate evenings playing in performances of Figaro (with a different conductor, Eliahu Inbal) and of the other Figaro masterpiece, Rossini’s II barbiere di Seviglia.

Even over that schedule the hour in which I attended seemed to be exceptional. By the time the orchestra was ready at 1.10pm, after the break, we started on another take of Bartolo’s ‘La vendetta,’ the soloist Kurt Moll, looking Wagnerian rather than Mozartian in his beard. The resonance rattled one’s ears, until the skipping triplets at the end brought an effect hardly possible in the theatre, the big voice scaled down into the cleanest, crispest half-voice. With two other superb takes already in the can (if that is what you call it now that digital recording has taken over) ‘La vendetta’ once through was quite enough. At 1.15pm Kiri Te Kanawa appeared on stage, while Sir Georg rehearsed a few points in the introduction to the Countess’s other great aria, ‘Dove sono’.

Happily with the players going through such an intensive Figaro period points were entirely on interpretation, not technical at all. Moving from the right of the stage up to the centre as she delivered ‘E Susanna non vien…’ Kiri Te Kanawa then proceeded to match and even outshine what we had heard earlier in ‘Porgi amor’, a real performance with all its tensions. Several small retakes of detailed passages, and there was the master-take of a key passage, all completed before 1.40pm. It was a mark of Kiri’s precision that when Christopher Raeburn asked her to go back for a moment to the earlier part of the aria, the production and timbre were subtly but definitely different from what we had just heard in the same melody as sung the second time round.

At 1.40pm Samuel Ramey appeared, the chosen Figaro. Selecting the cast some two years ago, Solti insisted that there should be no compromises. An ideal cast, he insisted, costs relatively little more in relation to the total budget than an indifferent one, and this for Figaro was based on his much-praised Paris production. But for the role of Figaro himself he made a change, lighting on Ramey, a young bass from New York who had much impressed him and is now increasingly being heard in Europe. Hearing playbacks one registered the clarity and precision, ideal for recording. In the studio Ramey promptly sang ‘Se vuol ballare’ and there was no retake, not even a fragment. Then shrewdly Raeburn asked him (and Kiri) to record the scrap of recitative when later in the opera that defiant number is briefly recalled. It was now 1.47pm and still the session was not over. Solti was murmuring inaudible instructions to the orchestra (as he explained later ‘I never have to raise my voice’) when suddenly identifiable thoughts emerged on a bubbling call of ‘Diddle-diddle-diddle-diddle-diddle …..Could it be? Yes it was: the Overture came rushing, fast, precise and resilient, an ‘egg-timer’ performance of the freshest kind, in which Solti swayed like a prize-fighter, knees bent, head thrust forward. At 1.54pm he dismissed the orchestra, an unbelievable six minutes early.

Over the 10 days of Figaro sessions, Solti’s schedule was unremitting – generally a piano rehearsal with soloists in the morning, followed by the orchestral session, 11am to 2pm. A brief rest in the afternoon (except when being interviewed by Gramophone) led to evening sessions on the recitatives, every line of which (unlike some recording conductors) Solti insisted on supervising. Figaro, he explained to me, was the first opera he ever conducted when as a young répétiteur in the Budapest Opera House, he was suddenly told to go on with no rehearsal, having conducted only twice before at all at small symphony concerts, it was the day of the Anschluss, he remembered, 11 March, 1938, when Hitler annexed Austria. It is the opera which, as he claims, he has conducted more than any other over the years, and it is perhaps surprising that in the recording studio it has come last for him among the supreme Mozart masterpieces, following Don Giovanni, Cosi fan tutte and The Magic Flute. He counts himself lucky to have waited long enough to find so intensely musical a cast, very much a team he feels, all highly intelligent with clean-cut recording voices, all with a sense of humour. It was significant that in the control room soloists listened to takes of all the other singers, not just their own. There during the playback of Bartolo’s aria for example was the Susanna, Lucia Popp, putting a pencil comically like a moustache between nose and upper-lip in character parody of the old man. Others in the cast were Thomas Allen as the Count, Frederica von Stade as Cherubino, Robert Tear as Basilio, Jane Berbié as Marcellina. There was even the ‘luxury’ (as Solti put it) of having Philip Langridge as Don Curzio and Yvonne Kenny as Barbarina.

For these June opera sessions Solti counted himself ‘egotistical’ to insist that they should take place in London with his own LPO. It allowed him to have a welcome stay at home in his splendid North London house. But by far the greater number of Solti recordings these days come from the great American orchestra with which he has now served a full 12 seasons, the Chicago Symphony. ‘How many concerts do you think I have conducted with that orchestra?’ he asked me aggressively, when we discussed his recording plans back at his house. I made a pathetic guess, only a fraction of the true figure of nearly 600. That being so, he says, he and the players know each other very well indeed, and recording sessions go faster than anywhere. He is aware even more acutely than most recording conductors of what the essentials are in a good record, not a patchwork of different and careful takes but as near as possible a real performance. That day he had just received the finished copy of his new version with the Chicago orchestra of the Mahler Second Symphony (6/81), a recording in which the instrumental movements were all done on single takes. Only a few vocal passages needed re-takes. Even the massive choral finale was substantially just a single performance, yet where in a concert small errors would not matter and the spirit was everything, here one could find playing that, as he boasted, could remain a demonstration of the period’s best well into the 21st century. Did he listen to his earlier LSO version of 1966 (11/66) before making the new record, I asked? Yes, he had, but only after an intensive new study of the score. With all repertory works, he felt, there was a danger from conducting them too much, and with the Mahler Second he had had eight years fallow, not touching it at all. That gave him the welcome chance of coming back to it totally fresh. As for differences of interpretation, he left that for me to judge when I did my comparisons.

Another work he has re-recorded is Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, but much of his recording activity with the Chicago orchestra is being devoted to Bruckner as well as Mahler. Along with the keenly awaited recording of Tippett’s Fourth Symphony, the Bruckner Fourth is one of the new issues brought out to celebrate the Orchestra’s current tour of Europe. The plan is now to complete the Bruckner series in Chicago.

With the LPO Solti has just recorded two Haydn Symphonies, (Nos 96 and 100) as well as the Bartók First Piano Concerto with Vladimir Ashkenazy as soloist, completing their series. The original idea was to have Solti at the keyboard with Ashkenazy in the Bartók Sonata for two pianos and percussion, but finding the time to put in the necessary practice – not to mention rehearsal with Ashkenazy – in the end proved too much for Solti and the second pianist will now be Ashkenazy’s son.

Next year for his annual opera recording, again with the LPO, Solti hopes to record Verdi’s Forza del destino, an opera he is specially fond of. The cast is not finally decided, but it would be surprising if Luciano Pavarotti did not take part.

After that comes the great Bayreuth project – three Ring cycles in 1983, 1984 and 1985. Solti only agreed to conduct The Ring at Bayreuth, if he could have a say in the choice of producer and designer. The result is that following the controversial Ring cycle with Patrice Chereau producing and Pierre Boulez conducting, Bayreuth will have Solti in the pit and Sir Peter Hall producing with designs by William Dudley. Both Sir Georg and Sir Peter have long cherished the idea of doing The Ring at Bayreuth, and fortunately their ideas seem to coincide very happily. He no longer likes abstract productions of Wagner, and modernistic re-interpretations like Chereau’s grow boring on repetition, he insists. The time is ripe, he feels, for a naturalistic, realistic production which takes account of Wagner’s very detailed stage directions, not disregarding any fire, the sword or the forest, but presenting realism with all resources that you have on the modern stage.

Hearing about all this activity made me wonder when Solti finds time to rest, but he insists that nowadays he does only the work he wants to, and that this year he was taking his holiday from 8 July to 26 August. But even then he has one or two engagements on his hands. For a BBC Television ‘Workshop’ he was taking part in rehearsals and a performance of a movement from Mozart’s G minor Piano Quartet. ‘I shall have to sit down and practise,’ he said, ‘but I shall enjoy that.’

Back to Georg Solti / Back to Hall of Fame