The disastrous premiere of Bruckner's Third Symphony, by Adrian Murdoch

James McCarthy

Thursday, November 1, 2012

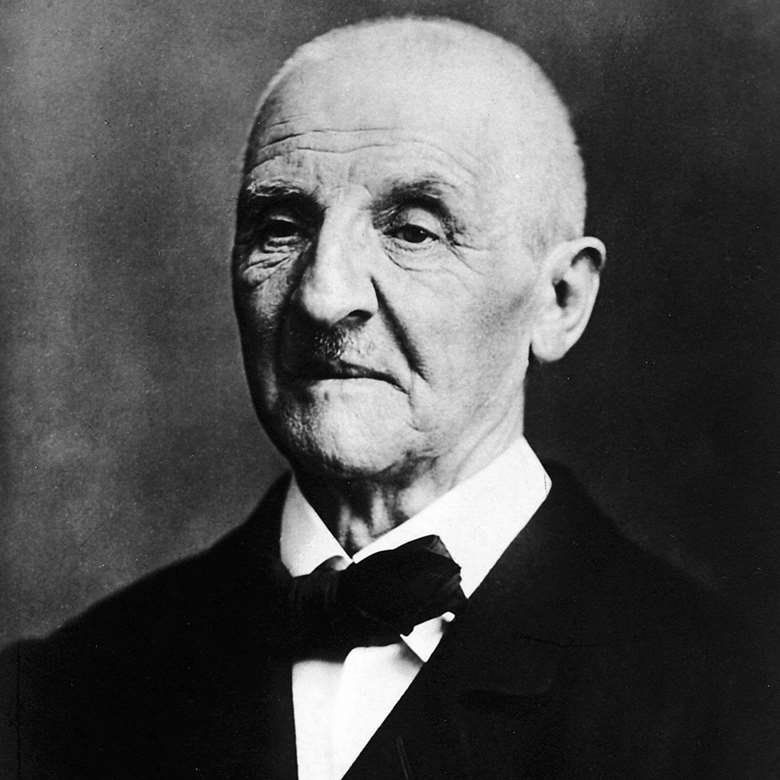

Public ridicule, heckling and cat-calling. Not even the most avant-garde of contemporary composers playing to a jaded and obstreperous audience today would expect such a reaction. But that was the reception given on Sunday, December 16, 1877, to one of the 19th century's greatest composers. The premiere of Anton Bruckner's Third Symphony in D minor – the 53-yearold Austrian's first mature and monumental symphony – under the direction of the composer himself was an unmitigated disaster and was to prove to be the worst fiasco of his life.

In retrospect, this should have surprised few. Bruckner's first concert in four years was a comedy of errors from the outset. The writing itself had been difficult. Bruckner had started what he called his Wagner Symphony in autumn 1872 and worked on it until the end of December 1873. In Bayreuth in September that year he had doorstepped his hero Richard Wagner, then preoccupied with The Ring, to get him to look through his unfinished Third Symphony and his Second Symphony in C minor. Although Wagner had liked the work (fondly nicknaming Bruckner 'The Trumpet' because of its brassy opening) in the beer-induced revelry that followed that evening, when Bruckner woke up the next morning he could not remember which symphony Wagner had agreed to have dedicated to him. He had to drop 'The Master' a note to confirm that it was indeed the Third.

Bruckner finished his third full set of revisions five years later, on April 28, 1877 – he would revise the symphony a number of times more before his death – and a performance was planned for later in the year. His friend Johann Herbeck, director of the Vienna Musikverein and one of the composer's staunchest musical allies, had volunteered to conduct it. Unfortunately Herbeck died suddenly on October 28. Somehow, though, the concert was saved. A performance by the Vienna Philharmonic was rescheduled for the second of the winter concerts in December, but Bruckner had to conduct it himself.

The rehearsals were a fateful prelude to the evening itself. Bruckner had never had an amicable relationship with the Vienna Philharmonic, nor was he the most fluent conductor. A wag in the orchestra had dubbed his Second Symphony the Pausensymphonie – the symphony of pauses – much to the composer's chagrin, and the score was originally sent back to him with 'unplayable' scribbled on it. Even after positive reviews of its first performance in October 1873, Bruckner's offers to dedicate it to the orchestra went unanswered.

When the musicians saw the score of his Third Symphony, they were even less impressed and remained uncooperative throughout rehearsals. The effusive dedication to Richard Wagner, 'to the unreachable world-famous sublime master of poetry and music', prejudiced opinion from the outset. The allusions to Wagner's music throughout (the famous cascading strings from the Tannhäuser Overture being the most obvious) compounded matters in a city that was stubbornly anti-progressive and anti-Wagner. In frustration, just before the premiere Bruckner wrote to a friend in Berlin: 'I shall never submit any of my works to our Philharmonic again for they have rejected my offerings repeatedly.'

One of the composer's friends, Theodor Rättig, owner of the publishing house Bussjager & Rättig, attended most of the rehearsals. 'It was a pitiful and scandalous spectacle,' he wrote, 'to see how the young players in the orchestra made fun of the old man's incompetent conducting. Bruckner had no real idea how to conduct properly and had to limit himself to giving the tempo in the style of a marionette.'

The evening itself could not have been a greater humiliation. Most of the audience had bought tickets as it was the farewell performance of the musical director of the court orchestra, Joseph Hellmesberger. After what was in any case a long concert, the new Musikverein concert hall on the Karlsplatz had begun to empty even before Bruckner had taken up the baton. As an atrociously obstinate Philharmonic began to play, many in the audience began to hiss their disapproval of the music. Instead of applause between movements – standard before the 20th century – the dribs and drabs of people leaving became an exodus.

By the time of the finale, the audience numbered no more than 25. This 'little host of hardy adventurers', as one reviewer called them, was made up of a dedicated hardcore of fans and pupils (of whom the 17-year-old Gustav Mahler was one), as well as a few who had stayed behind to laugh and heckle, shouting out 'da capo' and 'bis'. Bruckner was left alone at the rostrum, the orchestra having delivered its own final editorial comment by vanishing even before the last notes had died away. Friends rushed up to comfort him but he was inconsolable. He shouted at them: 'Let me go. People don't want anything of mine.'

Bruckner was mauled in the press when the reviews appeared two days later. Most generous was the Wiener Zeitung, which only called the Third 'audacious' and 'peculiar', if unrestrained and undisciplined. The Deutsche Zeitung was baffled. 'We heard an utterly bizarre work which might rather be described as a motley, formless patchwork fabricated from scraps of musical ideas than anything that is signified by the melodious title "symphony".' The influential and famously caustic 52-year-old critic Eduard Hanslick writing in the Neue Freie Presse, could not restrain his venom. 'Bruckner's poetic intentions were not clear to us – perhaps a vision of Beethoven's Ninth becoming friendly with Wagner's Valkyries and finishing up being trampled under their hooves' was his much-quoted conclusion.

The composer was despondent at the city-wide sniggers. He was cheered only that Rättig offered to publish the work at his own cost. An arrangement as a piano duet was also prepared by Mahler and another student, Rudolf Kryzanowsky. Both were published the following year.

Nonetheless, so traumatised was he by the symphony's reception that Bruckner stopped composing for almost a year. As for the Third, it was to be revised several times until it reached the more familiar 1889 version. Although this 'premiere' was greeted with 'storms of applause' when it was performed almost exactly 13 years later, on December 21, 1890, by a more amenable Vienna Philharmonic under the baton of Hans Richter, the memory of the debacle remained with him.

Fourteen years after that dreadful first premiere, one of his pupils recalled walking Bruckner home one evening. On the way to the composer's home, a fourth-floor flat at Hessgasse 7, on the corner of the Schottenring, they heard dance music coming from a house. Nearby the body of a famous Viennese architect lay in state. As they passed, Bruckner said: 'Listen. In that house there is dancing and over there the master lies in his coffin. That's life. It's what I wanted to show in my Third Symphony. The polka represents the fun and joy of the world and the chorale represents the sadness and pain.'