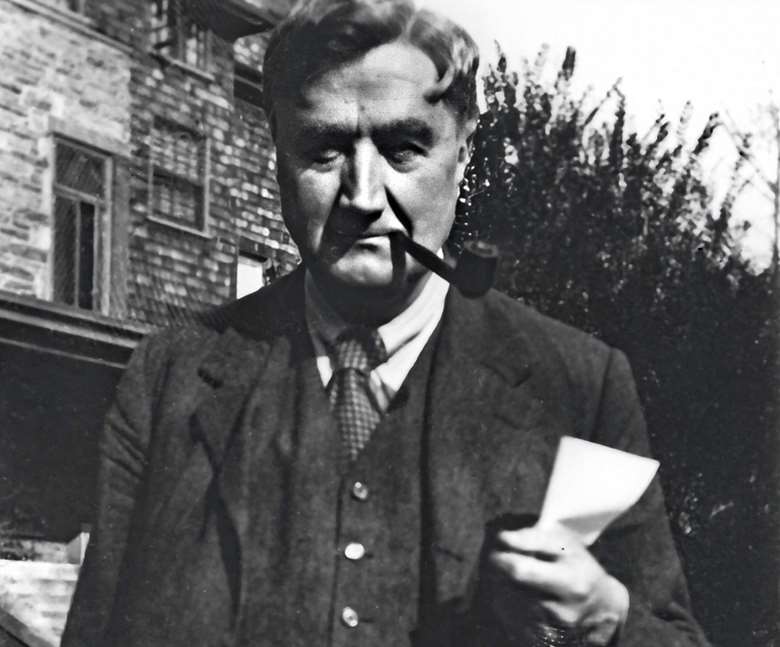

Vaughan Williams’s Concerto for Oboe and Strings: a guide to the best recordings

David Threasher

Wednesday, July 5, 2023

Vaughan Williams’s 1944 Concerto for oboe and strings is one of few such works to maintain a foothold in the repertoire. David Threasher listens to a selection of the available recordings

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter