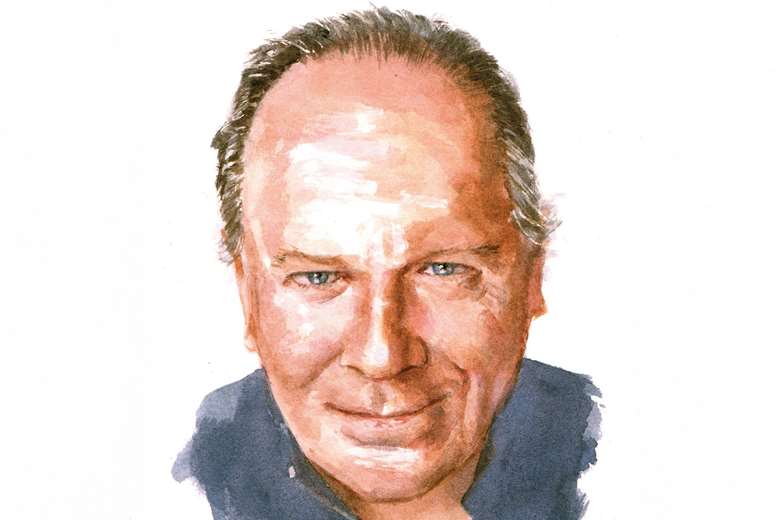

William Boyd on writing his first opera libretto: "this tiny spark that ignited over lunch all those years ago has now come to full incandescence"

Friday, May 16, 2025

The author on the path to writing an opera with Colin Matthews for the Aldeburgh Festival

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter