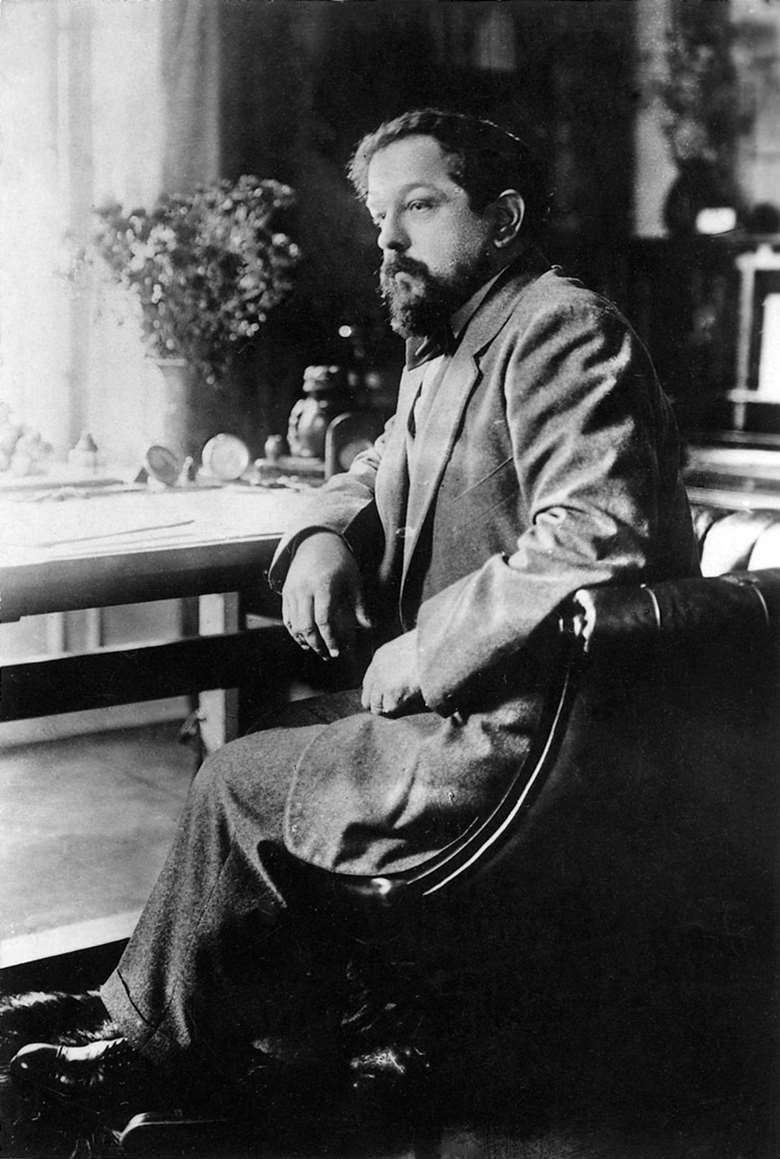

The Debussy legacy

Mark Pullinger

Tuesday, April 10, 2018

His use of colour influenced composers from Stravinsky to Boulez, but to call him an Impressionist misses the point finds Mark Pullinger, as he talks to musicians a century after the composer’s death

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter