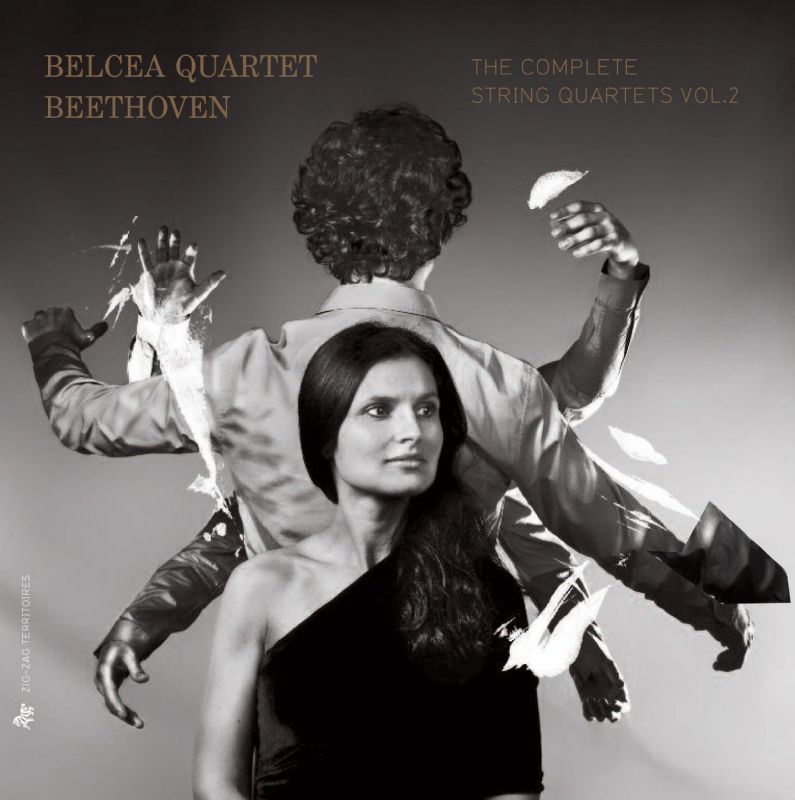

BEETHOVEN The Complete String Quartets, Vol 2

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Ludwig van Beethoven

Genre:

Chamber

Label: Zig-Zag Territoires

Magazine Review Date: 08/2013

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 287

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: ZZT321

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| String Quartet No. 3 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Belcea Quartet Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

| String Quartet No. 5 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Belcea Quartet Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

| Grosse Fuge |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Belcea Quartet Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

| String Quartet No. 7, 'Rasumovsky' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Belcea Quartet Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

| String Quartet No. 8, 'Rasumovsky' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Belcea Quartet Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

| String Quartet No. 10, 'Harp' |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Belcea Quartet Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

| String Quartet No. 13 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Belcea Quartet Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

| String Quartet No. 15 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Belcea Quartet Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

| String Quartet No. 16 |

Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer

Belcea Quartet Ludwig van Beethoven, Composer |

Author: Nalen Anthoni

Involved intensity is uppermost in the Belcea’s ethos and intensified in the first movements of Op 59, though in each case they raise the stakes differently. A pair of loud chords with silent bars between a very softly played questioning theme in No 2 herald a driven Allegro, changes in rhetoric shaped to accentuate nervy force. In contrast, a rhythmically pliable but expansively shaped principal subject on the cello accentuates the spaciousness implied in the Allegro of No 1, and within a steady pulse, a new theme (0'44") is lyrically slanted. These musicians don’t shy away from bending phrase or tempo, or suspending time while tiptoeing through the fugue later on; or baulk at time suspended in the third movement, Adagio molto e mesto, the sadness of Beethoven’s tribute to a dead brother graphically perceived.

Artistic imprints pierce the surface, the added marking sotto voce inviting not only an undertone but probably a response to an undercurrent of inner disturbance, too. The Belcea go ‘below the voice’ when instructed but also mine a subtext; and in the Cavatina of Op 130, subtext extended, they overlay the dynamic with a shadowy angst that almost chokes on itself in the C flat section marked Beklemmt (‘oppressed’). Stick if you will to Beethoven’s original scheme of following this penultimate movement with the Grosse Fuge and the jarring switch from tears to tempestuousness doesn’t faze the artists at all. Upheaval emerges in a fire-power of ferocity. Extremes meet head to head. Alongside formidable technical expertise is a pervasive determination to confront the knottiest of issues, caution be damned. Euphony isn’t all either. Yet clarity of line and attention to texture are not sacrificed.

Neither is a care for fine detail. Detected in the introduction to Op 74 by composer/musicologist Robert Simpson are ‘labyrinthine harmonies and mysterious touches’, the music ‘lit from within by a deep, quiet, human warmth’. And Beethoven begins sotto voce as he does the slow movement of Op 59 No 1 – but now in a new context. The Belcea heed the difference and don’t replicate the breathy hush of tragedy they seek to convey in the earlier work; instead their timbre and volume reflect gentle calm, a reflection too of punctilious preparation and depth of thought.

Reflected thus throughout the set as well, even at the other end of the subjective spectrum represented by the Scherzo of Op 135, a disquieting movement of syncopations and suppressed energy, the Trio a crazy whirl, the whole form lifted to another stage in its evolution. These players relish every second of extroversion before Beethoven reins in for what he called ‘a sweet song of rest, a song of peace’ – intent made explicit in the evocative marking Lento assai, cantante e tranquillo. Inner privacy returns; the Belcea reach under the wraps, again aware that expressions of solitude have their individual sense of time. And they space out the message, from a theme of simplicity in D flat transformed through hesitations in the C sharp minor second variation to its fragmentation and stilled coda in the tonic. Was the follow-through, a toss-up between ‘Must it be?’ and ‘It must be’, the ‘difficult decision’ in the Grave introduction to the finale, meant to be jocular? Joseph Kerman thought it a poor joke. The Belcea disagree but sense ambivalence, and go against received wisdom by postponing an answer until the coda of the ensuing Allegro when the slyly humorous objective eventually breaks cover. The last laugh?

Possibly; yet within the contradictions of his genius, Beethoven’s most personal fervour may rest in the slow movement of Op 132, conveying a ‘Holy Song of Thanksgiving to the Godhead from a Convalescent, in the Lydian Mode’. The Belcea’s grip on the atmosphere of profound gratitude and joy is absolute, changes of metre and mood laid bare through a numinous aura ineffably mysterious and circumspect. Remarkably, a complete command of gossamer traceries at the softest levels, heard in all performances, is heightened at the end; the final chord fades out in a wispy thread.

This is the Belcea single-mindedly fathoming the emotional recesses of the composer’s psyche, every interpretation steeped in a pregnancy of feeling, a vast recreative experience that harks back to the untrammelled foresight of the Busch Quartet at its best – but reconsidered and revitalised for our time. Yes, it’s that good.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.