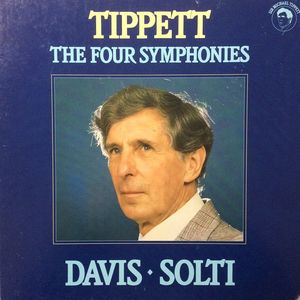

Tippett Symphonies

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Michael Tippett

Label: London

Magazine Review Date: 7/1990

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 171

Mastering:

DDD

ADD

Catalogue Number: 425 646-2LM3

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 1 |

Michael Tippett, Composer

Colin Davis, Conductor London Symphony Orchestra Michael Tippett, Composer |

| Symphony No. 2 |

Michael Tippett, Composer

Colin Davis, Conductor London Symphony Orchestra Michael Tippett, Composer |

| Symphony No. 3 |

Michael Tippett, Composer

Colin Davis, Conductor Heather Harper, Soprano London Symphony Orchestra Michael Tippett, Composer |

| Suite |

Michael Tippett, Composer

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti, Conductor Michael Tippett, Composer |

| Symphony No. 4 |

Michael Tippett, Composer

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Georg Solti, Conductor Michael Tippett, Composer |

Author: Arnold Whittall

I hope it will not be too long before we have new CD versions of Tippett's symphonies by one orchestra under one conductor, perhaps with the Concerto for Orchestra thrown in. For the time being, however, these four first recordings are good value on three CDs, and the fascination and originality of the music is strongly reinforced by bringing them together.

The symphonies parallel Tippett's evolution, embodied most powerfully in his operas and choral works, from the distinctive but still relatively traditional language of the 1940s to the more progressive style of his later years. The Symphony No. 1 (1945) may betray inexperience, both in its proportions and in the less than lucid polyphony of its slow movement (a problem which, Tippett's critics will claim, resurfaces and intensifies in the contrapuntal welter of the Symphony No. 3), but its emotional, stylistic world is fully fashioned, and in no sense immature. Sir Colin Davis sculpts its craggy profile with magnificent assurance, though I find the tempo of the first movement a little on the stolid side, and the work's more lyrical passages too weighty; something the tonal brightness but shallow perspective of the recording may exaggerate.

The recording of the Symphony No. 2 (1957) also has a rather narrow dynamic range, but this actually goes some way to clarifying the intricate contrapuntal strands in a superbly integrated account of a work in which the fruitful stimulus of Stravinsky enhances Tippett's own personal voice. This symphony does have a finale problem: the fourth movement seems too short, and lacks the sense of dialogue between its own diverse materials and the reassertion of the first movement's main idea that might have ensured an appropriately momentous climax. But the first three movements are among Tippett's finest inspirations.

At 55 minutes the Symphony No. 3 (1972) is a hugely ambitious score; a large-scale, two-movement first part followed by a second part centering on a sequence of songs for soprano that seems to universalize the character of the freedom-fighter Denise from the opera The Knot Garden. The whole elaborate score is swept up into a final cataclysmic confrontation between the human instincts of aggression and compassion, just as allusions to the incompatible musical worlds of Beethoven and the blues yield to the stark polarities of Tippett's personal modernism. It is the great virtue of Davis's performance that the emotional essence comes across with utter conviction, whatever doubts one may have about the coherence of this or that page of the score, and the tenacity with which Heather Harper and the LSO keep up the emotional temperature, however extreme Tippett's technical demands on them, compels unstinting admiration.

After this the Symphony No. 4 (1977) is less challenging, less complex, even featureless on occasion, despite the skill with which its successive episodes are differentiated and balanced. But Solti's performance is strongly shaped, and the excellent sound-quality confirms the eloquence as well as the brilliance of the Chicago ensemble. With the Suite in D (1948) as make-weight, this is a well-filled, as well as musically rewarding set.'

The symphonies parallel Tippett's evolution, embodied most powerfully in his operas and choral works, from the distinctive but still relatively traditional language of the 1940s to the more progressive style of his later years. The Symphony No. 1 (1945) may betray inexperience, both in its proportions and in the less than lucid polyphony of its slow movement (a problem which, Tippett's critics will claim, resurfaces and intensifies in the contrapuntal welter of the Symphony No. 3), but its emotional, stylistic world is fully fashioned, and in no sense immature. Sir Colin Davis sculpts its craggy profile with magnificent assurance, though I find the tempo of the first movement a little on the stolid side, and the work's more lyrical passages too weighty; something the tonal brightness but shallow perspective of the recording may exaggerate.

The recording of the Symphony No. 2 (1957) also has a rather narrow dynamic range, but this actually goes some way to clarifying the intricate contrapuntal strands in a superbly integrated account of a work in which the fruitful stimulus of Stravinsky enhances Tippett's own personal voice. This symphony does have a finale problem: the fourth movement seems too short, and lacks the sense of dialogue between its own diverse materials and the reassertion of the first movement's main idea that might have ensured an appropriately momentous climax. But the first three movements are among Tippett's finest inspirations.

At 55 minutes the Symphony No. 3 (1972) is a hugely ambitious score; a large-scale, two-movement first part followed by a second part centering on a sequence of songs for soprano that seems to universalize the character of the freedom-fighter Denise from the opera The Knot Garden. The whole elaborate score is swept up into a final cataclysmic confrontation between the human instincts of aggression and compassion, just as allusions to the incompatible musical worlds of Beethoven and the blues yield to the stark polarities of Tippett's personal modernism. It is the great virtue of Davis's performance that the emotional essence comes across with utter conviction, whatever doubts one may have about the coherence of this or that page of the score, and the tenacity with which Heather Harper and the LSO keep up the emotional temperature, however extreme Tippett's technical demands on them, compels unstinting admiration.

After this the Symphony No. 4 (1977) is less challenging, less complex, even featureless on occasion, despite the skill with which its successive episodes are differentiated and balanced. But Solti's performance is strongly shaped, and the excellent sound-quality confirms the eloquence as well as the brilliance of the Chicago ensemble. With the Suite in D (1948) as make-weight, this is a well-filled, as well as musically rewarding set.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.