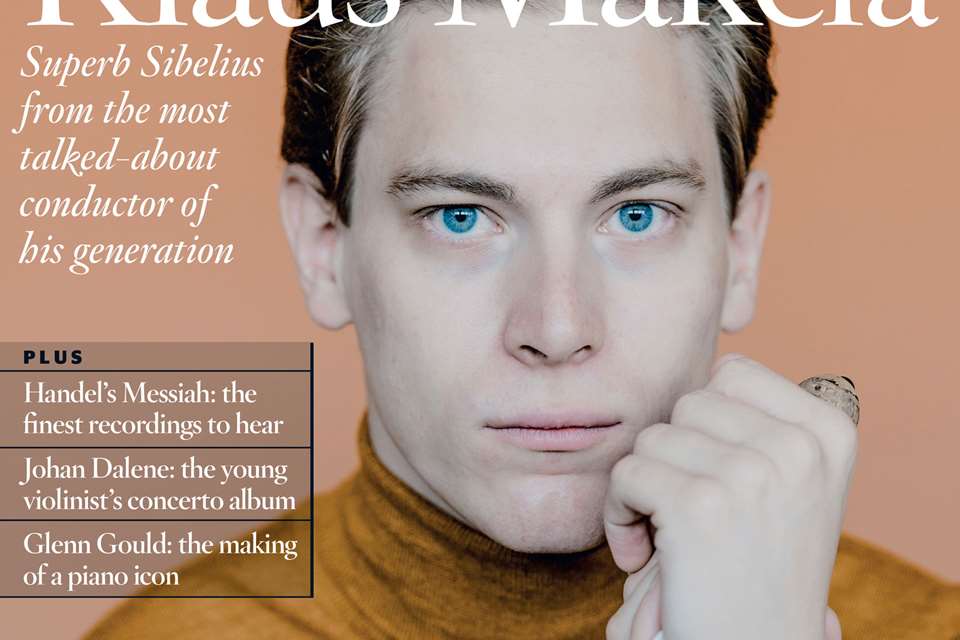

Klaus Mäkelä interview: ‘You don’t have to play for the hall; you just have to seduce the microphones’

Andrew Mellor

Friday, April 22, 2022

Still in his twenties, the Oslo Philharmonic’s Chief Conductor Klaus Mäkelä is remarkably clear-sighted about what he wants to achieve and how – even after lockdown required a different approach to recording his debut album of the Sibelius symphonies, writes Andrew Mellor. Photography by Marco Borggreve

Sweet are the uses of adversity. Klaus Mäkelä’s inaugural season as Chief Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic should have been woven through with the sounds of Sibelius’s seven symphonies, presented in concert and in order, from autumn 2020 to spring 2021. Decca would have harvested the fruits of all that labour, releasing a full Sibelius cycle to launch its new relationship with the conductor. Then, well … you know what happened next.

Mäkelä’s symphony cycle did get made, but under circumstances as exceptional as they are probably unrepeatable. Orchestra and conductor immersed themselves in Sibelius and only Sibelius for much of the spring of 2021, slowly sculpting their take on the symphonies and Tapiola in studio conditions. Outside the Oslo Concert Hall, Norway lay in silent lockdown.

Sibelius is not new to the Oslo Philharmonic. The composer conducted the orchestra three times during the spring of 1921 – a century before these sessions almost to the day. But, claims Mäkelä, this concentrated engagement with the scores changed his ensemble’s understanding of them. ‘We played, played, played and then recorded,’ he says. ‘It allowed us to dig deeper than would have been possible in a normal season.’ Distancing of 1.5m between players only fostered keener listening in his musicians, reports the conductor.

‘It was a funny thing. The Sibelius sessions were the only social interaction many of us had, when everything was forbidden’

The process also fast-tracked Mäkelä’s kinship with those musicians in a season blighted by stopping and starting, chopping and changing. ‘Recording teaches you so much about your colleagues,’ he says. ‘You quickly learn how to make everyone feel they can give their best at any particular moment. You get to know which musicians you can push a little and which ones will need a little more space; which thrive on pressure and which don’t. And it was a funny thing: these sessions were the only social interaction many of us had that spring, when everything was forbidden.’ Would he retake his inaugural season in Oslo, if he could? ‘In terms of building a relationship with the orchestra, this was absolutely the right way.’

He wasn’t building on sand. Mäkelä first conducted the Oslo Philharmonic on May 16, 2018, in an event described by the orchestra’s Head of Artistic Planning, Alex Taylor, as ‘not ideal’ – falling the day before Norway’s all-consuming national day and featuring a bitty programme of Nordic sweetmeats and national songs, albeit with Sibelius’s Seventh for carbs. And yet – ‘We knew from the first rehearsal that this was something really special,’ remembers Taylor.

New concerts were hastily arranged in order to get Mäkelä back to Oslo, and by October the orchestra had offered him the top job. His contract was then extended by four years (to seven) before it had even started; with so much interest in Mäkelä from elsewhere, reasons Taylor, it was essential to secure some longevity. Next, Mäkelä was announced as Daniel Harding’s successor as Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris from 2022. Soon that contract was altered too: brought forward to 2021. In March of that year, Decca signed Mäkelä – the first addition of a conductor to the label’s roster since it welcomed Riccardo Chailly in 1978.

So, is this cellist-turned-conductor from Finland the real deal? He certainly appears to be. I first saw him conduct a subscription concert with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra in November 2018, from a cheap front-row seat at the Helsinki Music Centre that meant I could almost reach out and touch his heels. Nearly all the music was new, conducted with interpretation not just noise management. Since then I have been as impressed by his laconic technique as by the particular depth of sound and structural nous he seems to draw from whatever orchestra he finds himself in front of. He is also a joy to watch – elegant, precise, entirely natural, yet often unpredictable.

‘You have to find a balance between paying enough respect to an orchestra’s culture and adapting to get the most out of the players’

Three days after the conductor’s 26th birthday, we meet at the Oslo Concert Hall where he is recording Shostakovich’s Symphony No 6 (a complete Shostakovich cycle will follow the Sibelius on Decca, split into single-disc releases). All is calm in the session, but still Mäkelä manages to tighten the thread of the symphony’s sparse, elusive opening Largo – full of exposed brass and wind, treacherously difficult to record. He is unusually specific about what he wants and uncommonly lucid in his explanation of it. At one point he sings three similar phrasings of a simple, oscillating minor third, citing the one he wants and the two he doesn’t. At another, he reminds his musicians: ‘You don’t have to play for the hall; you just have to seduce the microphones.’

‘The orchestra is used to projecting, but if you do that for the microphones then it can sound quite tight,’ Mäkelä explains in his dressing room afterwards, its walls adorned with black-and-white portraits of his predecessors from Johan Halvorsen to Vasily Petrenko. One portrait, of course, sticks out. ‘The spirit of Mariss Jansons lives very strongly here and that’s a beautiful thing,’ says Mäkelä. ‘He built up the quality of the orchestra by insisting on precision and preparation. And even now when people come to work on Monday morning, they are prepared.’ That can’t be said of every orchestra in a Nordic capital.

To claim that Mäkelä enjoys recording is an understatement. ‘I absolutely loved the whole process,’ he beams, discussing the Sibelius. ‘It was wonderfully exhausting!’ His strategy for the Shostakovich is clear, and he imparts it with similar clarity and confidence: ‘Tomorrow we will play the whole symphony through; people will know what they can do better, and that will be more or less what we use.’

It’s possible to while away many an hour watching Mäkelä conduct on YouTube. Until now, there have been virtually zero commercially released recordings carrying his name. Should a studio recording be seen as something separate from a live performance – even if that live performance is recorded or filmed? ‘Yes, I think so. The reason for making records in the studio, especially in Sibelius’s case, is that you can help the balance and textures come out or blend in a different way. On a studio recording, there should be this illusion of it all happening at once, though you have to be careful that it’s not too optimal – not too much.’ Who will buy it? ‘That is a good question. I think there is a market for a new cycle. It is so easy to listen to music these days.’

Mäkelä’s responsibilities did not stop at the Sibelius sessions. He estimates having spent 150 hours editing the results, and suggests his producer Jørn Pedersen ‘probably then spent two or three hundred more just by himself’. For his part, he loved every minute. ‘Editing is really constructing the symphony again. In one take of Sibelius you might have a syncopation that is very clear and in another it might be completely muffled. Finding the right pieces to put together has been really satisfying.’

You would expect nothing less of an avid listener. Mäkelä takes me through his setup. ‘At home I have studio monitors from Genelec. If I have to edit, I use Sennheiser HD 800 S headphones. If I travel, I have different kinds of earphones or headphones with noise cancelling, and I listen through Tidal.’ He opens the app on his phone, which promptly throws up Andris Nelsons’s recent recording of Shostakovich’s Sixth. Sizing up the competition? He laughs: ‘I try not to listen to works I’m conducting, as I might unconsciously copy something, and that’s not nice. But I subscribe to new orchestral release playlists because I’m interested in what people are recording. If it sounds good, why does it sound good? Where was it recorded? In which hall? With what setup?’ He explains that it was ‘the sonic brilliance that is at Decca’s core’ which was part of the attraction of a contract with the label.

Editing the Sibelius, Mäkelä used as many different devices as possible. ‘Sometimes it’s important just to listen on an iPhone speaker, because even though the sound is bad, certain frequencies are projected which means you hear things you wouldn’t hear on the best editing headphones.’ The results will be available in Dolby Atmos – vital, the conductor believes, for the huge dynamic range of a symphony cycle that opens with a distant timpani rumble and lonely clarinet. ‘These days you can make a recording that allows people to really hear that, even when they’re sitting on an aeroplane.’

Historical recordings make up a good proportion of Mäkelä’s own playlists. He runs down the week’s listening: Mengelberg’s St Matthew Passion, Sibelius from Robert Kajanus and Armas Järnefelt. ‘The ways in which orchestras did things in the past teach you so much. Even if you compare the “old” Berliner Philharmoniker with the “old” Concertgebouw Orchestra, there are massive differences – far more so than now. It was a different culture.’

The last time Mäkelä had the score of Shostakovich’s Sixth open on a music stand was when he was conducting the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra on tour, negotiating different acoustics in Amsterdam, Reykjavik and Hamburg. The idea of sound culture fascinates the conductor but does not appear to faze him. ‘Different orchestras search for different things,’ he says. ‘You have to find a balance between paying enough respect to their culture and adapting so you get the most out of the players. It’s basically pulling strings, but you have to pull them more or less in the right order.’ He is convinced that acoustics are as important as ingrained traditions. ‘I strongly believe that sound comes from imagination. These days the quality of playing is so high that if you can dream of a sound, you can actually bring that sound to whichever hall you’re in.’ That could explain why the Oslo Philharmonic, in its acoustically lousy hall, is already sounding noticeably different.

Conversation turns to those grand old orchestras that like to lag behind the beat. ‘Then you have to be careful, because it’s disrespectful to simply ask them to play on your beat. There is always a way to be found.’ You can always trust a Finn to have an animal metaphor handy: ‘If you walk a dog, it can be nice to give it some space and have it on a long lead. But if another dog comes and your dog rushes towards it, it can be very hard to regain control.’

‘What would be ideal would be to build a sort of trust between conductor and audience that makes the audience want to hear something they haven’t heard before’

It is a curiosity of Mäkelä’s rapid rise that many of us who think we’ve followed his career from the start have only ever seen him conduct prestigious orchestras. Unlike a Robin Ticciati or a Gustavo Dudamel, there was no first job in provincial Scandinavia for Mäkelä. He assures me he served his apprenticeship, guest-conducting regional orchestras in Finland and Germany. ‘Back then, my work was focused on very different things,’ he remembers. ‘As a young conductor in front of an orchestra that needs guidance in practical things like timing and intonation, you take the music apart and put it back together again, and you basically learn the repertoire yourself during that process.’ And when you turn up at the Royal Concertgebouw or Chicago Symphony orchestras? ‘Good orchestras just play. All you can do is guide them a little bit in different directions. First, you work out how they react. Then you prioritise: what will make most sense for everyone to deal with now, that will have the biggest impact?’

Some orchestras ‘need more conducting’ than others, he says. His technique, meanwhile, changes depending on which one he is in front of. In Oslo, he holds back, encouraging his musicians to listen and react to each other with increasing sensitivity. ‘That feeling you can have with your own orchestra, just breathing in the same pulse and in the same way, it’s really wonderful; you can get addicted to it,’ he says. ‘And it’s personal too. They are a really wonderful group of people, but very serious and really engaged.’ It was telling to see Oslo’s galvanising concertmaster Elise Båtnes guest-leading the Orchestre de Paris under Mäkelä not long ago. ‘She is one of the best in the world … just amazing,’ he says.

As for technique, Mäkelä refers immediately to his teacher Jorma Panula: ‘His great strength was that he never told any of us what to do; he just let us figure out our style.’ Does he subscribe to the idea that every conductor has a sound, no matter what they do with their arms? ‘It is true. I think it has very little to do with your hands and arms, and very much to do with your presence. The more you conduct the more you realise that.’ He points to his forebear at another Paris orchestra, Myung-Whun Chung: ‘He is a master. He brings the same sound from every orchestra he goes to. He stands there with this sort of relaxedness, and out comes this amazing whoooooaarrr.’

Comparing the Orchestre de Paris with his Oslo orchestra, Mäkelä describes it as ‘equally wonderful but a very different group of people’. He is fired up by the success story that is the Philharmonie de Paris – the diverse, young and apparently limitless audience it attracts, and the bolder programming that that has allowed. He points to the same architecture-driven effect in Helsinki: ‘Remember, before the Helsinki Music Centre, concerts were not that well attended. Ten years after it opened, things are still sold out there, and consistently good programming has been a part of it.’

Oslo’s quest to build a new concert hall limps on. At the latest estimate, it is hoped ground will be broken on the waterfront site at Filipstad within the next five years. ‘We have a lot of hope,’ says Mäkelä, with the sure implication that a renewal of the orchestra’s audience will follow any new hall, and this in a city that has never felt more supercharged by the arts. ‘I can see the change in the public that has happened in Helsinki and Paris, and with that change comes an opportunity to introduce lots of different repertoire.’

In May 2020, I spoke to Mäkelä by phone about the predicament of Europe’s suddenly silenced musicians. He talked of finding inspiration in studying Beethoven’s Missa solemnis and of being able to play his cello. But he also referred to the clear sense of re-evaluation prompted by the shock of the pandemic. ‘It makes you think about everything,’ he explained back then, ‘and that leads you to evaluate what the role of a chief conductor actually is and what the connection with the audience means. We perform, we bow, we do our thing – our focus is on the music.’

Nearly two years later, has he answered his own rhetorical question? ‘What would be ideal would be to build a sort of trust between the conductor and the audience – the sort that makes your audience want to hear something they haven’t heard before.’ He has tried it, programming US composer Andrew Norman’s Sustain (2018) after Mozart’s unfinished Mass in C minor at the start of the current Oslo season, when audiences were permitted. ‘Only three people left after the Mozart, and all the chat after the concert was about the Norman,’ the conductor says. ‘These kinds of things, in the end, will pay.’

Mäkelä’s age clearly has less bearing on his conducting of music than on his consuming of it. Born in 1996, he is absolutely of the streaming generation. There is ‘great opportunity’ in the technology, he asserts. ‘Young people think much less in genres these days; you hear a piece of Classical chamber music, a piece of Arvo Pärt, a piece of easy jazz all put together. We [in classical music] have to learn to curate an experience that is attractive but substantial. And I think we can learn a lot from art museums, actually – about combining something old with something new, perhaps exploiting a theme or a contrast.’

In the end, he says, if his orchestras play well enough they will attract an audience by virtue of that alone. Mäkelä’s orchestras do play well – but then, they would. More interesting is the distinctiveness of his work with them. His Decca Sibelius includes some telling features, with occasionally heaving tempos that can speak of the slowing down of spring 2020 and a certain expressionistic tendency that aligns the music more with its European contemporaries than with the sort of characteristically Finnish well-articulated restraint. His Brahms has a mahogany quality and his Mahler is sturdy, while a recent menu of French music offered up in concert with the London Philharmonic Orchestra was deemed ‘simply exquisite’ by Tim Ashley in The Guardian. In Oslo, Mäkelä will conduct Bach (a B minor Mass is imminent) and plenty of Haydn and Mozart. ‘If you play really good Mozart you will probably play better Richard Strauss, because then you understand tension and release,’ he says. ‘It’s the same rules that apply, just with a bit more sugar.’

Nice turn of phrase. In fact, Mäkelä is a singularly impressive human being all round – softly spoken but firm; highly cultivated yet amusing, easy-going and absolutely of his time. Nothing comes out of his mouth without due consideration, but there is no sense that his words are hallowed, that they are any more important than yours or mine. I feel an urge to ask him about his obvious taste for luxurious tailoring; I can think of no other individual able to carry off a double-breasted suit in the third decade of the 21st century. But having stopped myself short of asking a female conductor about her attire recently, I feel I should extend Mäkelä the same courtesy. Does any of that even matter? A question for another day, perhaps. In the meantime, there is plenty about Mäkelä that your ears alone will be thankful for.

Mäkelä and the Oslo Philharmonic’s Sibelius set on Decca is reviewed in Gramophone's Reviews Database

This article originally appeared in the April 2022 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue – subscribe today