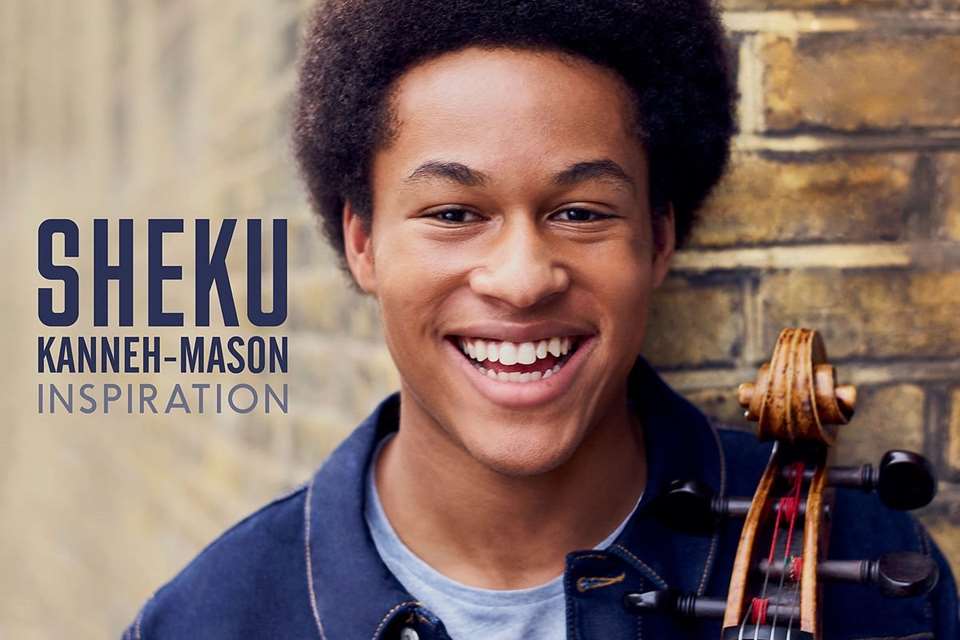

Sheku Kanneh-Mason interview: ‘Just playing beautifully is kind of boring. I want to play with as much character as possible’

Monday, January 13, 2020

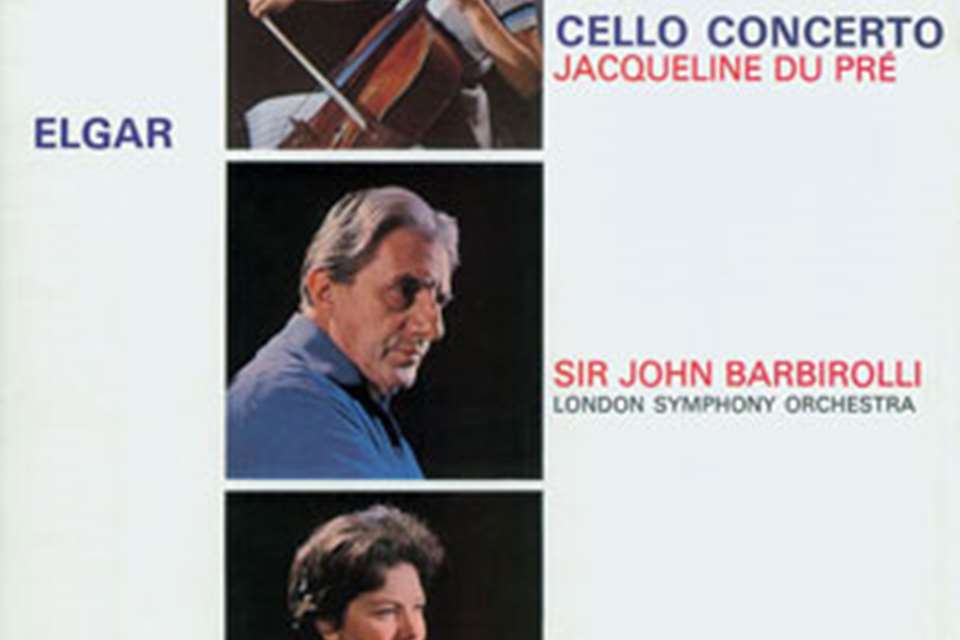

At just 20 years old Sheku Kanneh-Mason takes inspiration from the great cellists of the distant past – and his models for Elgar’s Cello Concerto are no exception, finds Richard Bratby

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter