‘There are some musicians who believe that just by playing a concerto they can bring people together – well, you can’t’ | Igor Levit interview

Michelle Assay

Tuesday, September 14, 2021

Igor Levit’s new album features two huge – and hugely significant – 20th-century works. Michelle Assay meets the pianist to explore their underlying meaning

A film historian friend once told me there are two kinds of genius: the Buster Keatons and the Charlie Chaplins. Keatons are extremely talented but struggle to keep up to date with market changes; Chaplins are just as adept at maintaining contemporary relevance as they are naturally gifted. By these lights, Igor Levit is surely more a Chaplin than a Keaton. And the analogy becomes even stronger when it comes to his adherence to left-wing causes. ‘I’m a child of my time,’ claims Levit. No disagreement here: his virtuosity bestrides social media and concert platforms with equal presence.

Levit’s Twitter feed was already in overdrive months before he started his now legendary lockdown house concerts (a series of mini-recitals, streamed via Twitter from his home in Berlin). Soon those concerts had become the internet sensation of the year and the media was flooded with interviews, features and fly-on-the-wall reportages. An entire book, Hauskonzert, co-authored with journalist Florian Zinnecker and published in April this year, follows Levit during the 2019-20 season, from his Twittergate protests against anti-Semitism and at least one notorious pre-concert harangue directed against hate speech, through a backlash that reportedly included at least one death threat, to the house concerts themselves, culminating in his award of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Igor Levit (photo: Peter Meisel)

According to Levit, the Twitter-streamed house concerts were not premeditated and simply started on impulse as a by-product of lockdown despair. He admits to having an insatiable need for an audience, for being heard. ‘Look, I have wonderful friends among musicians who think in exactly the opposite way. It [his constitutional inability to make music just for himself] was my main reason for streaming – just so that in theory I knew there were people on the other side to give me energy. If they didn’t exist, I don’t know what would have made me walk over to the piano.’

But it’s to the present and the future that we turn our discussion. Levit is joining me by Zoom from Vienna, where he is getting ready for a chamber concert with the cellist Julia Hagen later that evening. He is intense, alert and straight down to business, just as I had imagined him, except that there is not a sign of the playful humour that often enlivens his twittering.

‘I am not a living museum … I am driven by today. I refuse to think you understand a piece more because you know the context better’

I start by asking if he is thinking of adding a chamber music strand to his recording portfolio; he smiles and says he is not putting ‘any industrial pressure’ on it for the time being. His solo discography, however, is a different matter. His next major album, which is already being marketed as a ‘discographic tour de force’, is a three-CD volume that’s about as tightly packed as it can be. Packaged with a funky cover designed by New York Times Magazine illustrator Christoph Niemann, it juxtaposes Shostakovich’s 24 Preludes and Fugues, arguably one of the composer’s most abstract and apolitical ventures, with one of the most flamboyantly extrovert and politically engaged works in the piano repertoire, Ronald Stevenson’s Passacaglia on DSCH (1962) – an unbroken set of variations on Shostakovich’s musical monogram, lasting around 80 minutes. Stevenson’s work supplies the title for this set, ‘On DSCH’. Thinking of Levit’s previous albums ‘Encounter’ and ‘Life’, I wonder if ‘On DSCH’ carries some punning message about what Levit considers Shostakovich’s work to be – an autobiographical statement, perhaps? No, it seems, but also yes. ‘On DSCH’ is just that: a programme focused on Dmitry Shostakovich, directly and indirectly: ‘Stevenson’s title just nails it … I think it was Tatiana Nikolayeva who said about the Preludes and Fugues, “These pieces are a kind of musical diary.” There is surely something to that, and I can very much relate to that idea.’

Levit is undoubtedly formidably intelligent, but his rhetoric seldom allows for a two-way conversation. In fact, he sometimes seems to be engaged in a dialogue between two sides of his own intellect: between the compulsion to speak aphoristically and the awareness that issues are often more complicated than that. There are also evidently conflicting ideas involving music’s self-sufficiency as opposed to its connection with the world. He is certainly not one for the idea of music as a narrative, hidden or otherwise. ‘I often say, you can tell a certain story about a piece but there is a valid chance that the same piece will sound completely different to a listener or listeners. I am not a fan of pre-cooked narratives for musical works.’ Nevertheless, for his house concerts he offered his virtual audiences an introduction to the work, and even sometimes to its emotional content. So I ask him if he does a lot of research about pieces he plays. ‘I try to learn as much as I can; but at the same time, I am not playing pieces from the past – I am not a living museum. So as much as I try to internalise what information I receive from what I read, at the same time I am driven by today. I refuse to think you understand a piece more because you know the context better.’

He is therefore far from regarding the performer as a passive vessel. ‘If I didn’t walk to the instrument and play a piece, at this particular moment, what would you hear of the piece?’ He crumbles a biscuit wrapper – ‘Nothing, absolutely zero, just a piece of paper. So I am also an enabler. Nobody could convince me that without us, performers, these pieces would still be alive.’

‘Stevenson’s Passacaglia on DSCH is a combination of intellectual, pianistic, physical and emotional effort’

That leads him to a position which certainly allows for the idea of the Preludes and Fugues as a cycle – narrative or no narrative. ‘It wasn’t going to be any other way … You have 23 highly individual pieces, as if individual human beings are telling you something. These pieces are all highly intimate, very private and focused, one after another. And then everything culminates in the very last, the 24th, where I believe for the very first time you experience a communion, a coming together of everyone. So only in the end is there this very triumphant togetherness.’ Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues have been in Levit’s concert repertoire for quite some time, and although the conditions of performance have been highly varied, this central idea of 23+1 has remained very much alive for him: ‘It is always this experience I aim to make when I play in public: that we finally come together in the end.’ He admits he has been forced to choose a selection from the cycle when Covid constraints have necessitated interval-free concerts. ‘I’ve played the whole cycle so far once without an intermission, which was exciting, but I can’t do it too often. So when I was asked to play 45 minutes of Shostakovich, I just picked up a few. There was no plan to it. It wasn’t to my greatest enjoyment, but there was no alternative. I will try not to do it in the future!’

The quasi-programmatic nature of Levit’s idea about the cycle makes me wonder if he regards Shostakovich’s work as at any level a political statement, if only as a ‘secret diary’ of a damaged life. ‘First of all, it’s not only that his career was damaged – he was also an international superstar. And this is what makes his life so incredibly complicated. At the same time as he was at the highest possible risk and highest possible pressure from the authorities, he was also a superstar beyond belief.’ Here Levit is referring to the composer’s status both within and beyond the Soviet Union. ‘I am not undermining his tragedy,’ he adds, ‘I am just saying that it’s very complicated. You rarely can sum up a human being’s life by calling it “a tragedy”.’ And, as if thinking back over the various Twitter discussions, he adds: ‘A human being’s life is more complicated than 280 characters can express.’ So how does this relate to his music-making? It seems things are evolving in Levit’s mind. He admits, ‘There was a time in my life when I really tried to politicise everything I played. I’m over that now. Music has the potential to achieve quite a lot, but art in general doesn’t have to do anything, there’s no obligation – there is just a chance. And that’s the main difference compared with politics. Politics has an obligation.’

Levit has been outspoken in his political views and values, especially as concerns his international outlook. His website still carries his motto: ‘Citizen. European. Pianist’. He’s an avid campaigner against anti-Semitism and scathing about Brexit. But apart from the phrase ‘Russian-born’, which sometimes precedes ‘German pianist’ in articles about him, and brief references to his family’s move from Nizhni Novgorod to Hanover, when he was eight, there is little mention (least of all by him) of his Russian roots. Do those roots form any part of his identity, I ask, and do they in any way influence his relationship to Shostakovich’s work? A long silence – followed by: ‘I have to think about it … I’m not too emotional about my “on paper” homeland … Let’s say I can read in Russian. But I don’t approach this music differently because I was born in Russia.’

I try to push him a little further, but without much success. ‘I follow certain rules. I engage in topics I know something about. I would absolutely talk about Russia, and I have no reason not to. It’s just that I’m not into it … This is very different from speaking about European issues or the United States, which are closest to my heart.’ I wonder if I can elicit a more emotional response about Levit’s relationship to the most Jewish of the Preludes and Fugues, the painfully lamenting No 8 in F sharp minor. But now we’re back to aphorisms: ‘This is indeed a very Jewish-rooted Prelude and Fugue. It’s an incredible achievement.’

Igor Levit (photo: Felix Boede / Sony Classical)

Maybe I’ll have more luck asking him about pianistic challenges. He confesses to finding the G sharp minor Prelude and Fugue No 12 the most intense in this respect. This is the grand conclusion to the first half of the set, with a grave passacaglia for the Prelude and a highly convoluted fast Fugue in 5/4 time. ‘Everyone knows that No 15 is a pain’ – that’s the one in D flat, with a whirlwind, quasi-atonal fugue – ‘but No 12 is mentally very difficult: just a high-pressure piece, very dark and grim, and extremely hard to play.’ It was the same for Sviatoslav Richter, incidentally. That one of the most intelligent of virtuoso pianists and one of the most virtuosic of intelligent musicians should also struggle with an eight-minute Prelude and Fugue is somehow comforting and humanising.

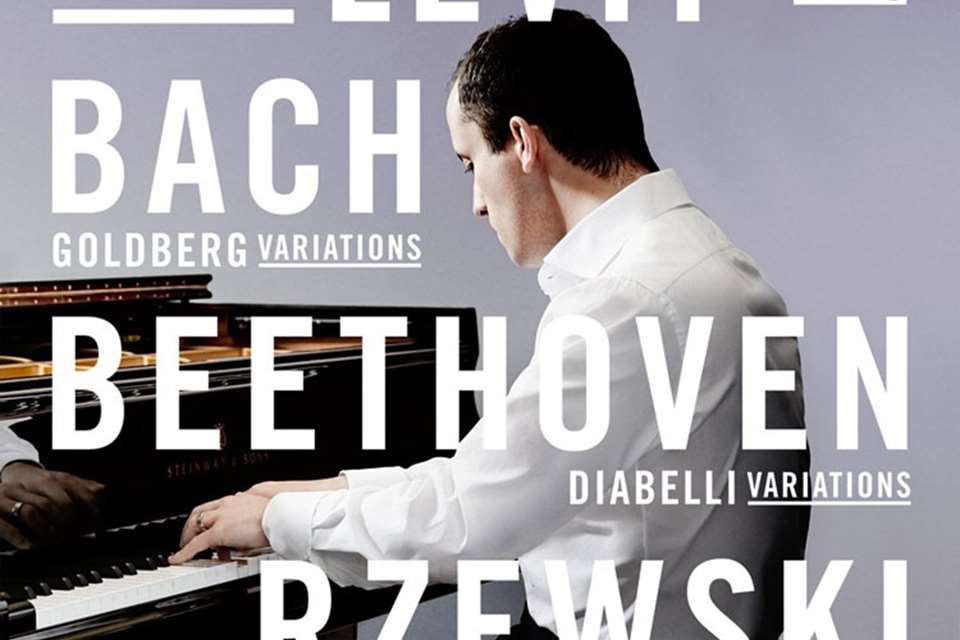

But with Stevenson’s monumental Passacaglia on DSCH, we’re in Levit’s favoured arena of the Titans. He tells me that he wanted to record the work in 2015, alongside the other variation cycles he set down at that time: Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations and Rzewski’s The People United Will Never Be Defeated! ‘For me its place is up there alongside other great variations … The only reason I didn’t record it then was that I just couldn’t pull it off. It just didn’t work. It was too early, and the work was too difficult, too extreme, too intellectually challenging. I wasn’t in the right place.’

He fondly recounts the story of his first encounter with the work back in 2009 or 2010: ‘I remember Matti told me about it.’ Matti Raekallio, his Finnish teacher whom Levit considers ‘a true source of inspiration and a dear friend’, was also the one who ‘threw me into the whole Busoni topic’ (Busoni taught Egon Petri, who inspired Stevenson, and Busoni’s Fantasia contrappuntistica is a clear predecessor of the Passacaglia on DSCH). ‘It was Matti with whom I worked on the Diabelli Variations, on most of Beethoven, in fact, and it was Matti who really threw me into the Ronald Stevenson bathtub, and I never really got out of it.’ After that, it was just a matter of time and series of lucky encounters. During a Birmingham concert at the invitation of artistic programmer Richard Hawley, where Levit played Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues (‘one of the first times I played them’), he met the couple John Humphreys, the Birmingham-based veteran pianist, and Joan Humphreys, the dedicatee of Stevenson’s piano transcription of the first movement of Mahler’s 10th Symphony. ‘John was very close to Stevenson. So here I was with two sources: Matti, who knew the piece, and John, who knew the man who composed it. And all doubts were overthrown.’ John Humphreys would also introduce Levit to Stevenson’s Mahler transcription, which he performed at Wigmore Hall, London, in 2018 with Humphreys in the audience. ‘And then I started really learning the Passacaglia on DSCH. The first six months were painful. And then, suddenly, boom! And I just pulled it off.’ He first played it in a late-night concert at the Heidelberg Spring Festival on April 5, 2019, then returned to it the following month at Wigmore Hall, and more recently in one of his pandemic-time house concerts.

‘The Passacaglia on DSCH is a combination of intellectual, pianistic, physical and emotional effort. So far it’s really been second to none for me. It’s a kind of larger-than-life piece that I feel very close to – a musical piece of genius beyond belief.’ But if the ambition and scope of Stevenson’s craftmanship are hardly in question (take for example the triple fugue on BACH, DSCH and the Dies irae in the final part), the ideological premisses of the work are another matter. Should we try to separate the music and its innovations from the communist sympathies that underpin it, or do we have to swallow the entire package? ‘I admire its international approach,’ he responds, dismissing claims about Stevenson’s overt communist sympathies as oversimplification suitable for Twitter-land. Then, as if realising that such dismissal is itself an oversimplification, he adds, ‘I’ve also performed The People United; I have certain sympathies, absolutely, but on ideological, theoretical levels.’ He also adds that he has admiration for both Isaiah Berlin, the Russian-Jewish-British liberal-pluralist philosopher, and Isaac Deutscher, the Polish-born internationalist-Marxist intellectual: ‘Even though they were diametrically different, I can admire them both.’ For Levit, it is above all the anti-nationalism of Stevenson’s work that resonates with his own beliefs. ‘The Passacaglia on DSCH is, in a way, the single most international piece I know; the approach is so Marxian, so wide; it goes beyond the idea of any borders. The surviving question becomes a human question and not a national question. This is an idea that I can totally relate to.’ Levit agrees that the idea (not that far, perhaps, from John Lennon’s Imagine) is highly utopian, but adds, ‘I would love us all to believe in that utopia.’

‘That’s something I find uplifting about music; it’s just there to be experienced, not to be explained. I am not a teacher’

This humanistic-internationalist understanding of Stevenson’s work is one way of steering around the dilemma of such overt allusions as its Lenin-referencing ‘Variations on Peace, Bread and the Land (1917)’ in the second part of the work. Later in life, when Stevenson’s political fires began to cool, he himself admitted that when he was writing the Passacaglia on DSCH it was from a point of view of young, naive, credulous conviction, but that he was ‘now prepared to believe that the rot set in with Lenin, not just with Stalin; I am now very interested in Solzhenitsyn’s ideas about the Soviet Union’ (from an interview with Martin Anderson in 1995). Levit feels no obligation to inform his audience about such a reference: ‘If I did not tell you that at a certain part of the piece there is a “Lenin quote”, you wouldn’t hear it; if I tell you, that’s a form of manipulation.’ For Levit, ‘Music is freer than certain figures of our industry on the writing side, or blogging side, are trying to make us believe. That’s something I find uplifting about music; it’s just there to be experienced, not to be explained. I am not a teacher.’ Not a preacher, either? I ask, and am not entirely surprised to hear: ‘Well, there are certain things I preach, actually.’ How different from Stevenson, who once said, ‘I am a musician and I don’t want to be involved in politics. If I have something to communicate to people, I think it’s best to do it in music.’

And yet the musical side of Levit’s mind is as strong as the political, and there is a realist mentally jockeying for position beside the idealist: ‘If you believe music will make fascists less fascist, then you’re just naive … There are some musicians who believe that just by playing a concerto they can bring people together – well, you can’t, not outside the hall. And inside the hall, it’s just ideology’ – though he earlier indicated togetherness is what he aims for in Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues. ‘Don’t think that Sibelius’s Violin Concerto will turn someone’s mind. I think that’s utter BS.’

Playing devil’s advocate, and taking a deep breath, I set forth another possible point of view: that despite their left-wing ideologies, and whatever we might think about those ideologies, composers such as Rzewski and Stevenson enjoyed an abundance of what is nowadays called ‘white male privilege’, as does Levit himself. I also point out that his repertoire is dominated by composers within the supposed white-male-privilege mainstream. How does this sit beside his desire for activism – which by definition suggests action rather than words? ‘You’re right,’ Levit answers. ‘The baggage of privileges I experience, unconsciously, is phenomenally big. But then, so what? It’s like asking someone who engages in climate-change politics why they take the plane; yes, I do, because I sometimes have to.’ He adds that he has several fields of engagement beneath the media radar, including support of young colleagues. But he doesn’t go into details, except that there are plans already in motion. ‘There’s nothing more to say.’

That’s literally true, because there’s no time left (if only Germans weren’t so damned punctual). And with that, my hopes of further probing vanish. Three days later, extraordinarily, Levit leaves Twitter, deactivating his account and abandoning his 145,000 followers – @igorpianist becomes #igorlevit, with the familiar maxim, ‘Life is more complicated than 280 characters.’ Two weeks further on, however, he returns, to pay tribute to his friend Frederic Rzewski: ‘Rest in Peace, dear friend. I am devastated.’ A 52-second video of Levit’s right hand playing the tune of The People United Will Never Be Defeated! has already been viewed 26,800 times, so the tweeting is back on track. Levit, on and off the stage, still wants to communicate, still needs the limelight. Chaplin might have smiled in recognition.

Welcome to Gramophone ...

We have been writing about classical music for our dedicated and knowledgeable readers since 1923 and we would love you to join them.

Subscribing to Gramophone is easy, you can choose how you want to enjoy each new issue (our beautifully produced printed magazine or the digital edition, or both) and also whether you would like access to our complete digital archive (stretching back to our very first issue in April 1923) and unparalleled Reviews Database, covering 50,000 albums and written by leading experts in their field.

To find the perfect subscription for you, simply visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe