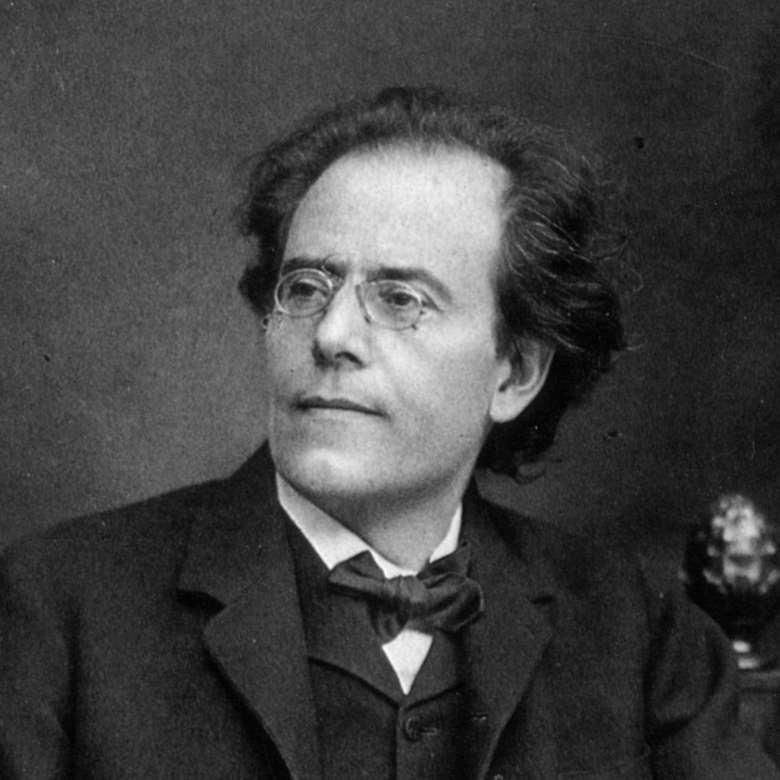

Gustav Mahler: Biography

Tuesday, October 2, 2012

Born: Kalischt (now Kalištĕ), Bohemia, May 7, 1860

Died: Vienna, Austria, May 18, 1911

‘Thin, fidgety, short, with a high, steep forehead, long dark hair and deeply penetrating bespectacled eyes’ – that was how the conductor Bruno Walter, Mahler’s one-time assistant, described him. He was also sadistic, a manic-depressive, an egomaniac, one of music’s great despots, a neurotic with a mother fixation (according to Freud, who analysed him) and undoubtedly a genius. As with his music, people either loved him or hated him. ‘The dedicated Mahlerians,’ wrote Harold Schonberg, ‘regard [those who dislike his music] the way St Paul regarded the Heathen. It is hard to think of a composer who arouses equal loyalty. The worship of Mahler amounts almost to a religion…Mahler’s [music] stirs something imbedded in the subconscious and his admirers approach him mystically.’

His tragic childhood stalked him for the whole of his life. His grandmother had been a ribbon seller, going from house to house selling her wares; his father had transcended these humble origins and was the owner of a small brandy distillery, married to the daughter of a wealthy soap manufacturer. It was an ill-tempered, badly matched marriage, one where the young Mahler frequently witnessed the brutality and abuse meted out on a long-suffering mother by an ambitious father. Of their 12 children, five died in infancy of diphtheria; Mahler’s beloved younger brother Ernst died from hydrocardia aged 12; his oldest sister died of a brain tumour after a brief, unhappy marriage; another sister was subject to fantasies that she was dying; another brother was a simpleton in his youth and a forger in his adult life while yet another, Otto, a humble musician, committed suicide rather than accept the mediocrity that fate had assigned him.

When he was six, Mahler discovered a piano in the attic of his grandmother’s house. Four years later he gave his first solo piano recital and aged 15 he enrolled at the Vienna Conservatoire. Here he not only developed as a pianist but won prizes for his compositions and discovered a talent for conducting. His professors noticed already the diligence and single-minded application that marked his professional career. Within a short space of time, conducting and composition took over his entire life with a totality that left little time for anything else. Realising he could not make a living as a composer writing the sort of music he dreamt of, he took up conducting, first in Bad Hall, Austria, then a permanent position in Laibach (now Ljubljana). In 1882 he moved on to Olmütz and the next year to Vienna and Kassel – the traditional path of the aspiring conductor, moving from opera house to opera house, slowly building a reputation. In 1885 he was in Prague, then got a break in Leipzig working in harness with another brilliant young conductor, Arthur Nikisch. In one season Mahler conducted over 200 performances, apart from editing a Weber opera, falling in love with the wife of Weber’s grandson and finishing his First Symphony. One thing that Mahler had in abundance all his life was energy, something he inherited from his mother. From his father came his drive and tenacity. His next step was to take over the Royal Opera House in Budapest from 1886 to 1888. Here he built up a fine company that won the praise of Brahms. When he moved on to Hamburg, Tchaikovsky himself allowed Mahler to conduct Eugene Onegin in his stead. ‘The conductor here is not of the usual kind, but a man of genius who would give his life to conduct the first performance,’ wrote Tchaikovsky.

Then, in 1897, Mahler quietly converted to Catholicism. Shortly afterwards he got the position he yearned for. With the enthusiastic backing of Brahms, he became artistic director of the Vienna Opera and soon after of the Vienna Philharmonic. He remained at the opera for 10 years and in that decade raised its fortunes to a height which some say has never been equalled since. Here he reigned as king, choosing the repertory, singers, staging many of the productions himself and overseeing every aspect of life in the opera house; he engaged the great stage designer Alfred Roller and experimented with lighting and stage effects: this was Mahler’s Wagnerian idealism put into practice – combining all the arts of the music theatre in a single man’s vision. Above all he moulded the orchestra into one of the finest in the world. The players respected him as a musician but hated him as a man, for Mahler’s quest for perfection and intolerance of anything smacking of second-best was implemented by an uncompromising martinet. He was the sort who’d pick on individual players and reduce them to tears – he even disciplined the audience, forbidding latecomers to enter during the first act. But every work that he laid his hands on came up ‘Herrlich wie am ersten Tag’, as they say in Vienna – ‘Glorious as on the first day’ – and he did it all at a profit.

Inevitably, he made enemies. Not just because of his despotic methods and lack of social niceties – he had no small talk and was nervous among people – but because he was a Jew and a genius. He was merciless with his tongue, with his contempt for those who opposed him and with his anger at those who failed to match his standards.

In 1901 he married the step-daughter of the avant-garde Viennese artist Carl Moll, Alma Schindler. She was beautiful, well-read and a composer in her own right, having studied under Zemlinsky, Schoenberg’s teacher. It was a remarkable marriage but one in which Mahler demanded complete freedom. His wife was to be mother, wife and amanuensis; she was to give up her composing and be totally subservient to his whims. The first five years of his marriage saw Mahler at the height of his powers and at his happiest. He continued to compose as he had during the previous decade in the one form to which he aspired and (to his austere way of thinking) in the purest, highest form of musical expression – the orchestral symphony. By 1906 he had completed the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh symphonies. Each one was vaster in scale than its predecessor; each one was met with hostility, misunderstanding and vituperation. Mahler was impervious to all around him, convinced that ‘my time will come’.

Then personal tragedy hit him. One of his little daughters died from scarlet fever. Mahler went insane with grief and forever after carried around with him the guilt that he had been responsible in part for his child’s death, guilt for tempting fate: in 1903 he had composed a set of songs using poems by Rückert entitled Kindertotenlieder – ‘Songs on the Death of Children’.

In 1907 he decided to leave Vienna and, the same year, was told he had a serious heart condition. The remaining three years of his life were focused on America. He first went to the Metropolitan Opera for two full seasons. Indifferent performances and the presence of Arturo Toscanini led to friction and more unhappiness. Worse came when he took over the conductorship of the New York Philharmonic in 1909. The audience disliked him, the orchestra loathed him, the critics reached for their poisoned pens. The feeling was entirely mutual. The Philharmonic, in Mahler’s words, was ‘the true American orchestra – without talent and phlegmatic’. The orchestra board was dominated by 10 wealthy American women. ‘You cannot imagine what Mr Mahler has suffered,’ Alma Mahler told the press. ‘In Vienna my husband was all-powerful. Even the Emperor did not dictate to him, but in New York he had 10 ladies ordering him around like puppet.’ In September 1910 he was in Munich to conduct the premiere of his mammoth Eighth Symphony, which met with overwhelming success, one of the few triumphs he ever witnessed as a composer. He returned to New York in late 1910 but early the next year collapsed under the strain of 65 rigorous concerts. An infection set in which serum treatments in Paris did nothing to alleviate. In a nursing home in Vienna, he died of pneumonia aged 50.