Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini: a guide to the best recordings

Jeremy Nicholas

Tuesday, July 14, 2020

Jeremy Nicholas surveys recordings of Rachmaninov’s impish masterpiece spanning nine decades

Rachmaninov at Senar, his villa near Lucerne (Bridgeman Images)

The last of Paganini’s 24 Caprices for solo violin, Op 1, has captured the imagination of many musicians. Paganini himself thought well enough of it to make it the subject of 11 variations and a finale. Liszt was the first to make use of it for the piano as one of his six Études d’exécution d’après Paganini (1838/40), revised in 1851 as the Grandes études de Paganini. Most famously, Brahms worked the theme through 28 prodigious variations (his Op 35). Believing there was still solo piano music to be mined from the theme, Mark Hambourg’s 16 Variations on a Theme of Paganini appeared in 1902; Ignaz Friedman’s Studien über ein Thema von Paganini, Op 47b (17 variations) was published in 1914.

Sergey Rachmaninov’s novel approach was to write his variations for piano and orchestra. He composed them during the summer of 1934 at Senar, his newly acquired villa near Lucerne. The manuscript is dated July 3 – August 18, 1934. The work was given its premiere in Baltimore just over 10 weeks later on November 7 with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski. Within a year, the Rhapsody had already established itself in the standard repertoire.

Rapsodie sur un thème de Paganini (it was the last time Rachmaninov used a French title for a work) is not really a rhapsody in the accepted sense but a straightforward set of 24 variations. These can be grouped by tonality: Vars 1‑11 in A minor; 12‑15 in D minor/F major; 16‑18 in B flat minor/D flat major; 19‑24 in A minor. It was his last concertante work and contains some of his best music.

It begins with an arresting ‘Listen up!’ nine-bar Introduction before the orchestra plays Var 1, marked Precedente (that is to say it precedes the statement of the theme proper), giving us merely its bare harmonic outline, with a similarity to the opening of the finale of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony that is surely more than a coincidence. After we hear the complete theme, Var 2 is further evidence that this music is not always going to be deadly serious. Vars 2‑11 continue without a break, slackening in tempo only at Var 7, in which Rachmaninov introduces what is tantamount to a second subject, a theme that turns up in no fewer than 17 of his works (roughly a third of his output) – the solemn tune of the ‘Dies irae’ from the Requiem Mass, which he combines with Paganini’s theme.

The tempo picks up again for Vars 8 and 9, the latter featuring the strings playing col legno (with the wood of the bow) and offering a serious coordination challenge to soloist and conductor. The ‘Dies irae’ theme returns in Vars 10 and 12 (Tempo di minuetto). The tempo returns to allegro, and even faster for the scintillating scherzando Var 15 for piano alone. Gradually the pace subsides, the mood changes – as does the key – and after the sinister Var 17, the sun comes out with the balm of D flat major and the most famous section of the work, Var 18, not conjured out of the ether like one of those poignant themes from Rachmaninov’s earlier piano concertos, but the five semiquavers of the Paganini theme, inverted, changed from a minor to a major key and slowed down to an andante cantabile tempo. Genius.

After that we embark on what could be seen as the final movement. Vars 19‑23 fly past at dazzling speed before a cadenza that leads to Var 24, known to some as ‘the crème de menthe variation’ because, so the story goes, Rachmaninov said he needed a tipple before playing the work with this most technically difficult of all the variations. The ‘Dies irae’ returns, blared out by the brass. There is a last tutti chord from the orchestra, played sforzando fortissimo, impishly undercut by the piano cheekily playing a fragment of the Paganini theme to give it the final word.

Rachmaninov and Moiseiwitsch

There are just shy of 400 recordings of the Rhapsody currently available in one form or another. The composer’s own classic account was made on Christmas Eve 1934 with the Philadelphia and Stokowski. Sergey Rachmaninov rejected a large number of individual takes and complete recordings during the course of his career. Significantly, on this occasion all six of the 78rpm sides issued were first takes. There is a leanness, a lightness of touch and an innate insouciance about his playing of the solo part that is utterly sui generis, a style which we must assume perfectly conveys the character of his score in the manner he desired. It is witty, playful, charming and musically sophisticated. But it is his use of rubato that is most striking, pushing ahead, slowing down, changing note values but always with a beguiling subtlety. Clearly, the composer’s own recording is an important legacy.

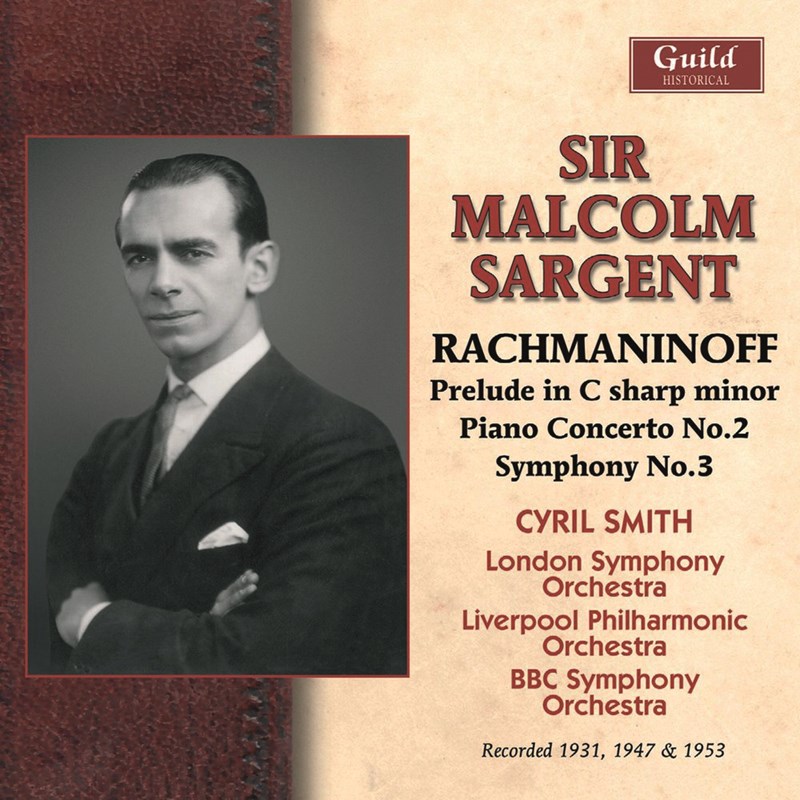

Issued on HMV’s prestigious red label, it was chosen by Benno Moiseiwitsch as one of the eight recordings to take to his imaginary desert island when he appeared on the BBC’s eponymous programme in October 1958 (‘If I listen to his playing it will bring back very happy moments that we used to spend together’). Moiseiwitsch recorded his friend’s Rhapsody twice, the first time in 1938 with the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and Basil Cameron. It was issued in the UK on HMV’s cheaper plum label. The Naxos transfer made from quieter RCA Victor pressings from the late 1930s is quite remarkably vivid. Tempos are even faster than the composer’s but few details are skated over, Moiseiwitsch bringing the same light touch and playfulness to the score as the composer. His second recording was made in 1955 with the Philharmonia under Hugo Rignold (EMI, 9/56 – nla) but sounds as though it’s been recorded through a blanket. There is also film of Moiseiwitsch playing Vars 18‑24 in the studio with Charles Groves. It was made in 1963, very shortly before his death, and when he was clearly below par. There are also live recordings available with Malcolm Sargent, from the 1955 Proms (Guild, 10/07), and Adrian Boult (Testament, 9/15).

Best avoided

A very different mood is created by Arthur Rubinstein in his 1956 recording with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He sees the Rhapsody as more ominous and sinister, the ‘Dies irae’ theme acquiring a greater significance than its place as a subsidiary role. I found it disappointingly dour and studio-bound. We shall also have to pass over the mercurial Shura Cherkassky after his curiously leaden Introduction (though naturally there are welcome individual and imaginative touches elsewhere). An absolute no-no, too, for Cameron Carpenter’s traducement of the work arranged for organ and orchestra (Sony Classical) – but useful for amusing your musical friends.

Americans from the ’50s and ’60s

The first thing that strikes you about William Kapell’s much-lauded account with Fritz Reiner and the Robin Hood Dell Orchestra of Philadelphia in his 1951 recording (RCA, 5/54) is the boomy acoustic. True, there is greater orchestral detail than on many more recent recordings – largely due to Reiner’s infallible ear rather than microphone placement – while his soloist is on typically fiery form. It’s all tremendously forceful and energetic and, of course, technically immaculate, but there are few moments of poetry. Better, in my opinion, is Kapell’s live recording, captured in October 1945 with Artur Rodzinski and the Philharmonic Symphony of New York. Tempos are slightly more measured than with Reiner, but after pausing for breath after Var 18 it’s the same steely, charmless chase to the end.

Julius Katchen’s ‘Rach Pag’ coupled with Dohnányi’s Variations on a Nursery Song has been a staple of the catalogue since it was set down in 1954. It has always been at or near the top of the pile. The recording in the much-missed Kingsway Hall was made 66 years ago but you really wouldn’t know it. Producer James Walker and engineer Kenneth Wilkinson achieved a near-perfect balance, the sound is vibrant and vivid, and the playing of all concerned is simply superb, capturing all the music’s drama, humour and lyricism without ever becoming portentous. Why the same team (Boult and the LPO) bothered to make a stereo remake five years later (Decca, 7/60) I don’t know. It is very little different.

I found the recording with Gary Graffman and Leonard Bernstein exemplary in its execution and observation but, though highly praised in some quarters, strangely bland and anonymous (unlike most of Graffman’s discography). Not so Leon Fleisher in 1957 with the Cleveland Orchestra under George Szell. Their recording, albeit sounding a little elderly now, simply fizzes with life and energy. The strings are crisp and piquant, and the way Fleisher slips into Var 18 is quite masterly (Szell shapes this section beautifully). What blows it off course are the final two variations, in which speed takes precedence over clarity. I had no idea what the piano was doing in the last few pages.

Earl Wild in Kingsway Hall again, with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under Jascha Horenstein in 1965, also captures the Rachmaninov/Moisewitsch spirit with effortless aplomb. It’s a classic account. Tempo relations between the variations are impeccably judged – try the link from Var 9 to Var 10 (poorly done by Rubinstein and Reiner) in which, for once, you can hear the glockenspiel, trombones and then the tuba play the ‘Dies irae’ under the piano’s bravura passagework. But, impressive as Wild always is, for my money at 20'32" it is all too breathlessly fast, with an insensitive Var 18 and the two final cadenzas pushed too hard.

The underrated and forgotten

The award for the most underrated version of this work goes to Leonard Pennario with the Boston Pops Orchestra under Arthur Fiedler. Recorded at Symphony Hall, Boston, in May 1963, the Rhapsody was Pennario’s debut on RCA. It is a performance that fulfils every criterion above – including the final glissando, the four bars of fortissimo octave trills three bars from the end (almost always drowned out) and the mischievous final two bars. These are not deal breakers, of course, but they represent the consistent excellence on show here. Pennario, undervalued and undeservedly overlooked, gives us, in almost every way, a great recording, with Fiedler highlighting Rachmaninov’s myriad conversational interjections with stylish aplomb.

Roger Fiske in the February 1962 issue of this journal thought the DG recording with Margrit Weber, the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and Ferenc Fricsay ‘starts well with some slick, venomous playing by the orchestra’ (quite right) but that ‘it is soon clear that this performance will emphasise the satire at the expense of the sentiment’ (not in my opinion). Weber, an almost forgotten Swiss pianist, died in 2001 at the age of 77. This recording (new to me) has the sound quality of its time (1960) but I like it enormously for its clarity and unshowy bravura.

More recent Rhapsodies

While Denis Matsuev uses the full sonority of his instrument to compelling effect, he lacks the playfulness of the composer, Moisewitsch and Wild, plays fast and loose with Rachmaninov’s dynamics and has trouble cultivating a true pianissimo tone anywhere. His partners are Valery Gergiev and his Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra.

The same conductor and orchestra accompany Lang Lang in a live recording. The Chinese superstar dispatches the solo part nimbly enough but without having anything personal to say. The piano is set well forwards, as are the double basses. Whether tweaked in the mix or too closely miked I don’t know, but in the first ‘Dies irae’ variation (No 7) they are obtrusive, their long pedal D flats at the end of Var 18 sound like a drone hovering overhead and they are even allowed to spill over into the tacet quaver and crotchet rests in the final bar.

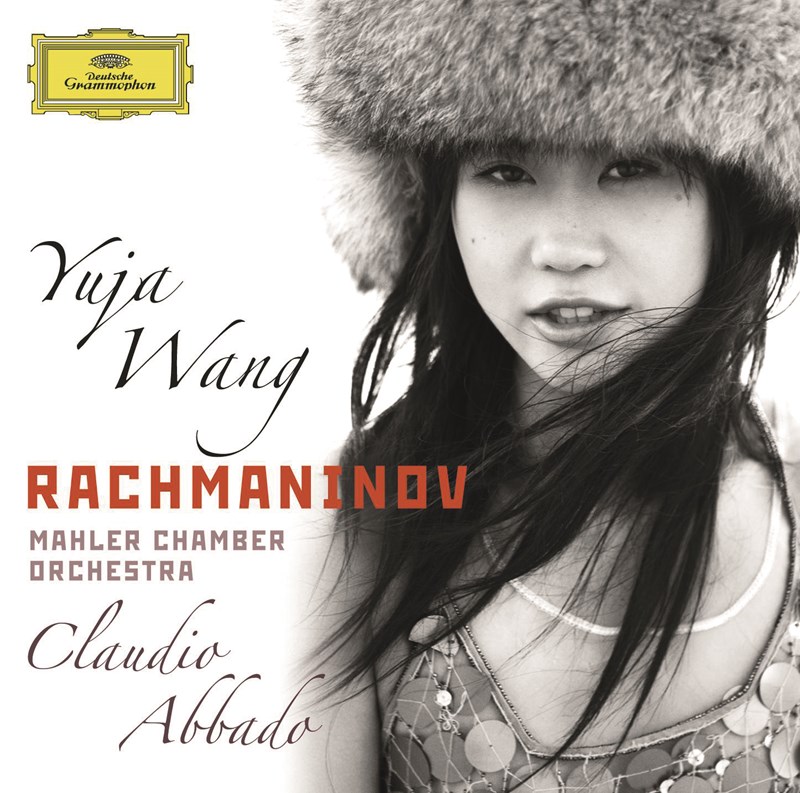

Yuja Wang, with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra and Claudio Abbado, is simply sensational (photo: DG)

Lack of space leaves me no room to commend in detail Simon Trpčeski (Avie, 9/11), Yevgeny Sudbin (BIS, 5/12), Jenő Jandó (Naxos, 10/90), Idil Biret (also Naxos), Jorge Luis Prats (Resonance, 9/90), Howard Shelley (Chandos), Philippe Entremont (Sony, 9/60) and Mikhail Pletnev (Virgin/Erato, 12/88) – all of whom I have much enjoyed – but particular mention must be made of the most recent entry to the lists by Behzod Abduraimov, the aptly located Lucerne Symphony Orchestra and conductor James Gaffigan (an Editor’s Choice in the May 2020 issue). Played on Rachmaninov’s own piano, this is a sizzling account from the top drawer, superbly recorded and accompanied. The coupling of his Symphony No 3 (also composed at Villa Senar) may or may not be an advantage, depending on your tastes and needs. I gave qualified praise to Anna Fedorova’s new recording in the April issue: I prefer her performance on YouTube with the Philharmonie Südwestfalen and Gerard Oskamp – well over 650,000 views to date.

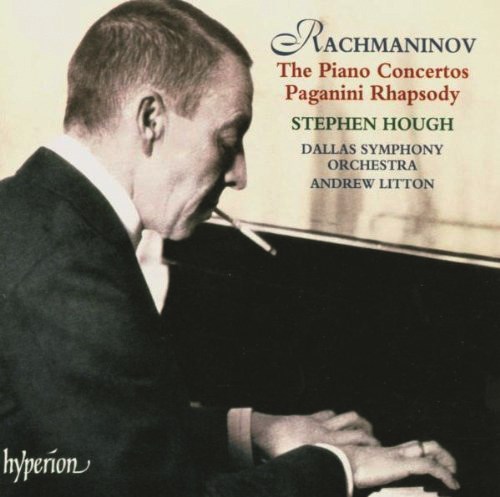

Listening to Stephen Hough’s 2003 recording on Hyperion (Andrew Litton conducting the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, and coupled with the four piano concertos), you are quickly aware of a more refined pianism. Clearly Hough knows the composer’s recording and has taken from that what he finds useful. Furthermore, he has made a close inspection of the score and decided that probably Rachmaninov knew what he was doing by acknowledging all the myriad dynamic and phrasing requests he thought best for his creation. Hough has then gone that one step further and made them his own.

More recently, there is Daniil Trifonov with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Yannick Nézet-Séguin. I welcomed this in the September 2015 issue when it was Gramophone’s Recording of the Month. The sound, as I mentioned, is ‘sumptuous, full-bodied and realistic, with a near-perfect balance between piano and orchestra. The Philadelphia’s silky strings and characterful woodwind are a joy, while the percussion department is suitably punchy without being overcooked.’ Trifonov is a brilliant soloist but, returning to it, there are moments towards the end where he over-interprets (such as the two final cadenzas) and loses tension.

Old favourites

Apparently, Vladimir Ashkenazy and André Previn simply played the work twice in the studio and decided no patching was needed. It shows. It is another classic account which from long affection I find hard not to place on the winner’s pedestal. Never mind ‘listen up!’ – the Introduction grabs you by the scruff of the neck: this is going to be a story worth hearing. Like Hough and Litton, there is a pianist-conductor on the rostrum who makes the orchestra alive to every nuance, someone who keeps the tone light-hearted but not overly so, relishing the splashes of orchestral colour and the composer’s knowing winks. It reminds us what a very great pianist Ashkenazy was at this time (1971). An obfuscated glissando (Var 24) and a flaccid last two bars are two (minimal) reservations.

Victor ludorum

One purpose of these pages is to choose the recording which presents the score as clearly as possible in a performance that transcends the bounds of the studio, is well balanced/recorded, has something vital and maybe individual to say about the music and which invites repeated listening. To nail the Introduction, Theme and all 24 variations faultlessly is well-nigh impossible. Three recordings come pretty close.

The first is by Cyril Smith, with Malcolm Sargent conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra in 1948. In his Gramophone review of November 1949, Lionel Salter, for whom I have the greatest respect, thought the performance was ‘superbly competent from all concerned (save for the sour oboe solo in Variation 16)’ – I wrote ‘lemony’ in my listening notes – with ‘a well-balanced soloist-orchestra relationship, excellent ensemble, a clean recording which captures every orchestral detail’. But in the end LS disliked it all because ‘the slickness of this performance leans over into flashiness’. Au contraire: I think it is exactly that quality that makes it so compelling and which brings out all the wit and brilliance of a score ‘abounding in ingenious effects of all kinds and yet profoundly musical in conception’ (LS). He feels it’s all about ‘sparkle and glitter’. I beg to differ. A tiny detail – the diminuendo Smith observes at bar 20 in Var 20 – is an example of his deep respect for the score. He is one of few pianists to observe this, as is his playing of the crotchet countermelody in Var 17, which LS perceives as ‘thumping his way through’. As for the D flat variation, schmaltz or not, it brought tears to my eyes, and you cannot gainsay that. And, glory be, the two final cheeky bars are played a tempo without the almost universal rit. This is a version to live with even if it is not quite in today’s state-of-the-art sound.

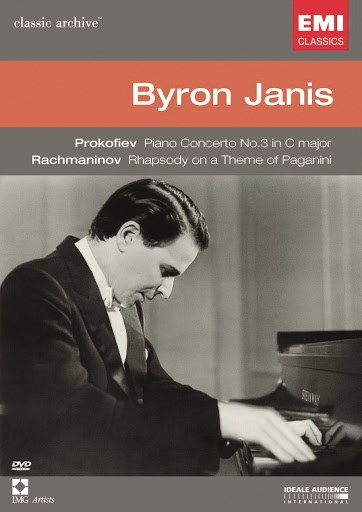

For the best on DVD, I am going to choose a performance that has a handful of fluffs, moments of wayward ensemble, is not in Technicolor 21st-century digital sound and indeed not in colour at all, but black-and-white. Ultimately, these elements are, for me, of lesser concern than getting to the heart of the composer’s aims and wishes; and if you want a version that captures every musical element and characterisation of the score, and at the same time see one of the greatest living pianists playing it live in concert, then you have to experience Byron Janis with the Orchestre Philharmonique de l’ORTF under Louis de Froment, filmed in Paris in 1968. I’ve watched it many times now and I shall return to it many times in the future.

But the recording that comes closer than anyone to getting all 24 variations right with equal consistency, discernment, accuracy and conviction, with suave, pinpoint orchestral accompaniment, with near-ideal recorded balance in a natural acoustic and with a simply sensational soloist is the one with Yuja Wang, the Mahler Chamber Orchestra and Claudio Abbado. At every point in the score where others fall short, you are left amazed at the way she and her conductor clear each hurdle and with such profound musicality: the pacing of the first ‘Dies irae’ variation, the phrasing of the scherzando (Wang has few equals here) and D flat variations, the electrifying ‘crème de menthe’, the gleeful glissando and final two bars – it’s all there, razor-sharp, impish and unerringly capturing the spirit of the composer. It’s a score that suits Yuja Wang to a T – T here standing for ‘technique’. And, as Nijinsky said, technique is freedom. Rachmaninov and Paganini would surely have been delighted.

TOP CHOICE

Yuja Wang; Mahler CO / Abbado

(DG)

To quote my original review, ‘The technical demands of the Rhapsody (Var 24 for example) hold no terrors for [Yuja Wang], of course, and her trademark impetuosity, which she injects into the bravura variations, is thrilling. But, more importantly, she is also an artist with that unteachable ability to tug at the emotions without recourse to sentimentality, as her playing of the famous Var 18 beautifully illustrates.’

BEST ON DVD

Byron Janis; ORTF PO / Froment

(EMI)

Byron Janis, still with us at 91, was in his prime aged 40 when he recorded this, just five years before psoriatic arthritis effectively ended his career. He relishes every moment of the virtuoso solo part and the persistent camera angle from above allows you see exactly what a physically demanding one it is. Electrifying in every respect.

BEST WITH THE CONCERTOS

Stephen Hough; Dallas SO / Litton

(Hyperion)

Stephen Hough is blessed in having a pianist-conductor who wears his (considerable) learning lightly and has himself long relished the delights, hidden and otherwise, of Rachmaninov’s superlative orchestration. And simultaneously – somehow – everyone seems to be getting off on the whole thing.

BEST HISTORICAL

Cyril Smith; Philh Orch / Sargent

(Guild mono)

The composer’s recording is a given – every home should have one – but recorded only a few months after the work’s completion (and though it might be heresy in some quarters), I think there is even more to be had from this score. For me, Cyril Smith and Sargent meet all requirements – and the sound quality on this CD is extraordinarily good.

Selected Discography

Recording Date / Artists / Record company (review date)

1934 Sergey Rachmaninov; Philadelphia Orch / Leopold Stokowski Naxos 8 110602 (3/35)

1938 Benno Moiseiwitsch; Liverpool PO / Basil Cameron Naxos 8 110676

1945 William Kapell; Philh SO of New York / Artur Rodzinski Pearl GEMMCD9194

1948 Cyril Smith; Philh Orch / Malcolm Sargent Guild GHCD2420 (11/49)

1954 Julius Katchen; LPO / Adrian Boult Dutton CDLXT2504 (9/54, 5/96)

1956 Arthur Rubinstein; Chicago SO / Fritz Reiner RCA 09026 63035-2 (2/57)

1957 Leon Fleisher; Cleveland Orch / George Szell Philips 456 775-2PM2 (3/99)

1960 Margrit Weber; Berlin RSO / Ferenc Fricsay DG 474 383-2GOM9 (A/03)

1963 Leonard Pennario; Boston Pops Orch / Arthur Fiedler RCA 19075 89927-2 (2/64, 5/19)

1964 Gary Graffman; New York PO / Leonard Bernstein Sony (24 discs) 88725 46239-2 (4/65, 1/14)

1965 Earl Wild; RPO / Jascha Horenstein Chandos CHAN10078 (12/81, 9/87)

1968 Byron Janis; ORTF PO / Louis de Froment EMI 310198-9

1970 Shura Cherkassky; WR SO, Cologne / Zdeněk Mácal ICA Classics ICAC5020

1971 Vladimir Ashkenazy; LSO / André Previn Decca 417 702-2DM

2003 Stephen Hough; Dallas SO / Andrew Litton Hyperion CDA67501/2 (A/04)

2004 Lang Lang; Mariinsky Th Orch / Valery Gergiev DG 477 5231GH (4/05); 477 5499GSA

2009 Denis Matsuev; Mariinsky Th Orch / Valery Gergiev Mariinsky MAR0505 (4/10)

2010 Yuja Wang; Mahler CO / Claudio Abbado DG 477 9308GH (6/11)

2015 Daniil Trifonov; Philadelphia Orch / Yannick Nézet-Séguin DG 479 4970GH (9/15)

2019 Behzod Abduraimov; Lucerne SO / James Gaffigan Sony Classical 19075 98162-2 (5/20)

2019 Anna Fedorova; St Gallen SO / Modestas Pitrenas Channel Classics CCS42620 (4/20)

This article originally appeared in the June 2020 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue – subscribe today!