Victor de Sabata: a maestro remembered

Richard Osborne

Monday, December 11, 2017

Richard Osborne pays tribute to the fine Italian conductor and composer notable for his interpretations of Romantic repertoire, who died half a century ago

Few conductors receive a standing ovation from an orchestra within 10 minutes of their first encounter. But that is what happened when Victor de Sabata led the London Philharmonic Orchestra through Berlioz’s overture Le carnaval romain in London in April 1946. Violinist Hugh Maguire, who would lead the London Symphony Orchestra in the Monteux era, recalled: ‘De Sabata was the greatest, the most musical conductor I ever came across: absolutely overwhelming. His knowledge of the repertoire, his control, his command, the thought, the study, the preparation – well, I didn’t know people like that existed.’

In addition to a superfine ear and a galvanising presence, de Sabata possessed an astonishing memory and yet more astonishing instrumental skills. Stories are legion of him demonstrating personally how to play difficult string arpeggiandos in Sibelius’s En saga or the flugelhorns in the finale of Respighi’s Pines of Rome at the dizzying pitch the composer prescribes. ‘Un chef vraiment extraordinaire’ was Ravel’s judgement after de Sabata conducted the premiere of L’enfant et les sortilèges – a score he had memorised within 12 hours of receiving it – in Monte Carlo in 1925.

De Sabata was born in 1892 in Trieste, Austro-Hungary’s most prized maritime possession. With its exotic mix of Italian, Slav, German and Jewish traders, it was Mitteleuropa writ large. The de Sabatas were typically Triestine: Victor’s father, a singing teacher and choral conductor, was Roman Catholic; his mother, an interested amateur musician, was Jewish.

Though not blessed with the best of health, the young boy was sent to Milan to study. Aged 25, he received a commission from La Scala to compose an opera, though it was his early tone poems – the emotionally explosive Juventus and the lambently beautiful meditation Gethsemani (both conducted by Aldo Ceccato for Hyperion, 7/01) – which musicians such as Toscanini and Richard Strauss chose to conduct.

In these early orchestral works we hear at first hand those magical sound worlds – luminous, clear, nothing smudged or uncertain – that would make de Sabata so mesmerising an interpreter of Wagner, Richard Strauss, Debussy and Puccini. Singers were especially aware of this: his celebrated accounts of Tristan und Isolde in Milan and Bayreuth were ‘light and poetical with a particular flavour that most conductors are unable to obtain from an orchestra’ (Gertrude Grob-Prandl); his Madama Butterfly was possessed of ‘a transparency that seemed like gossamer’ (Iris Adami Corradetti); Giulia Tess described a Salome in which ‘the translucent sensuousness was pure magic’.

As the distinguished Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli has noted, the orchestral sound de Sabata aimed for was not imposed on the musical structure: ‘Rather, it emanated from a deep reserve of feeling that conditioned that structure.’ Writing of de Sabata’s famous 1939 Berlin Philharmonic recording of Brahms’s Fourth Symphony (newly reissued, see below), Pestelli notes how the characteristic emphasis de Sabata brings to the staccatos, pizzicatos and syncopated rhythms ‘gives the symphony a gypsy colouring that blends curiously with its learned side’.

The kindest of men privately, de Sabata could be a terror in rehearsal. He is also remembered as an explosive presence on the rostrum. Nothing of value exists on film, though the blaze of his one-time assistant Carlo Maria Giulini’s filmed account of the 'Dies irae' of the Verdi Requiem is said to have something of de Sabata about it. There are, however, many striking prose evocations – an example being Vienna Philharmonic violinist Otto Strasser’s description of de Sabata dancing his way through Ravel’s Boléro, keeping strict time with his left hand and making all manner of subtle rubatos with the right. (Do not try this at home.)

This ‘temperamental’ aspect of de Sabata’s conducting meant that, for better or worse, live performances often took on an existence of their own. You can hear this to advantage in de Sabata’s 1952 Milan performance of Verdi’s Falstaff (Music & Arts), where the evergreen quality of the 64-year-old Mariano Stabile’s Falstaff is complemented by de Sabata’s high-voltage conducting and his relish for every jot and tittle of this famously protean score.

De Sabata succeeded Toscanini as Music Director of La Scala in 1930 and promptly resigned after a dispute with the orchestra over his ‘choreographic fairy tale’, Mille e una notte (‘A Thousand and One Nights’), a Bernstein-like score – ‘Richard Strauss meets Fred Astaire’, as Philip Clark has described it – of which Riccardo Chailly has made an appropriately de Sabata-like recording (Decca, 7/12). Toscanini was furious (no man loves his successor) and instructed de Sabata to resume his position.

De Sabata’s studio recordings came in tranches in a 21-year span from 1933 to 1954. The 1933 Parlophone recordings include his own account of Juventus, but it is the April 1939 Berlin Philharmonic recordings that are not to be missed. Apart from Brahms’s Fourth Symphony and a superlative account of Strauss’s Tod und Verklärung, the series includes a performance of Respighi’s Feste romane that is superior to Toscanini’s 1941 Philadelphia version in terms of the quality of the orchestral playing, de Sabata’s characterisation of the fairy-tale narrative, and the eradication of blatancy.

De Sabata made five recordings with the LPO for Decca in 1946, followed in 1947-48 by 11 recordings with the Santa Cecilia Orchestra in Rome. These include one of the most durable of all accounts of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony and the first ever recording of Debussy’s Jeux, a version that has yet to be surpassed (Testament, 4/98).

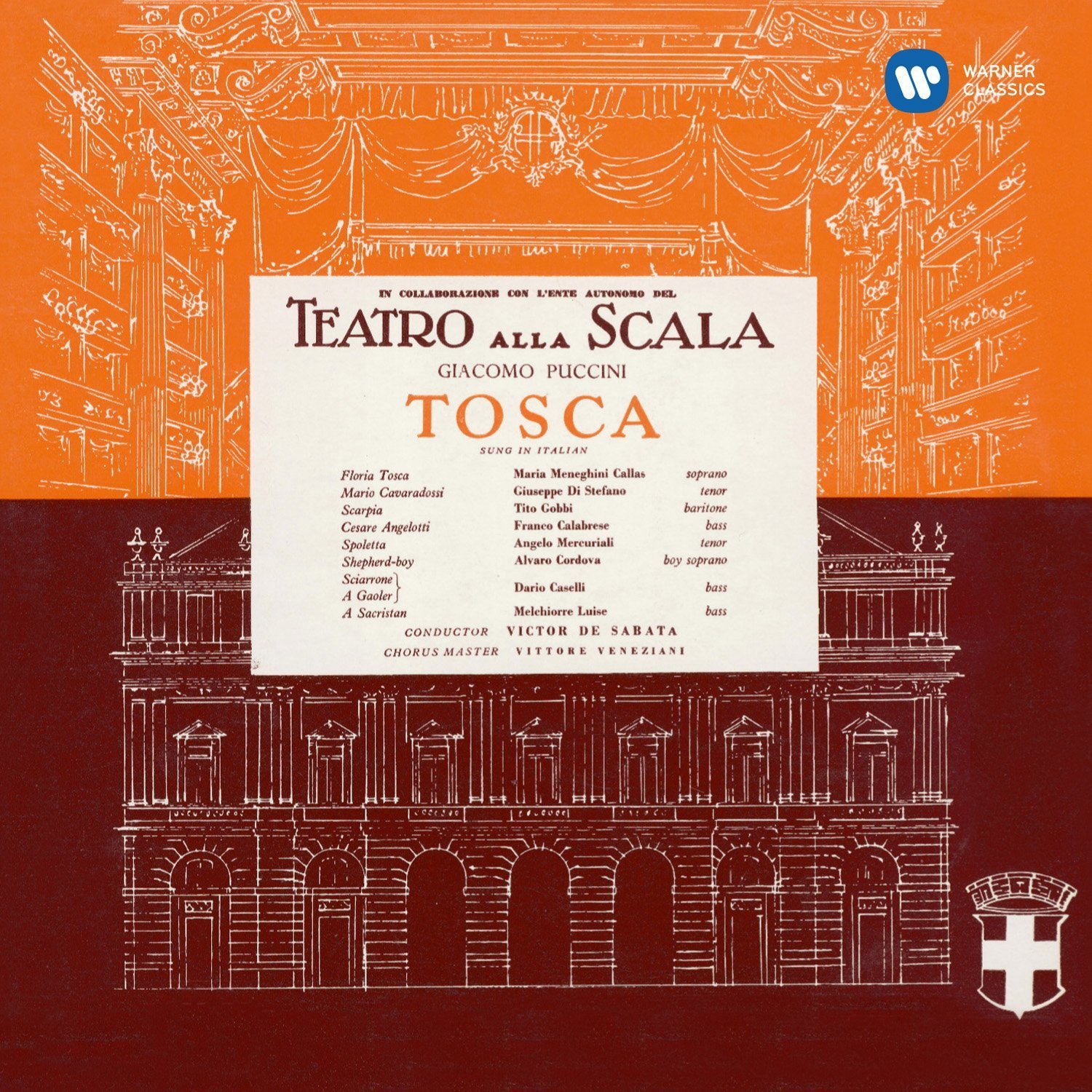

De Sabata’s first and, alas, only studio-made opera recording is the now legendary Tosca, produced by Walter Legge with an incomparable cast in Milan in 1953. If there is a more complete demonstration of an opera conductor’s art and craft than this, I have yet to discover it. Not soon after its completion, de Sabata suffered a heart attack that to all intents and purposes ended his public career. He was 61.

After De Sabata’s retirement the torch passed to the young Giulini and to Karajan, whose Tristan de Sabata had marvelled at in Berlin in 1938 and whose Italian career de Sabata promoted in the years 1942-56 when less generous-minded colleagues were barring Karajan’s progress in Austro-Germany. A closer comparison, however, might be Carlos Kleiber, another bright star which during its all-too-brief proximity to earth burned with a rare incandescence.

Defining Moments

1917-18 – Composer and conductor

His opera Il macigno is commissioned by La Scala, Milan; he is appointed conductor of the Monte Carlo Opera.

1930 – La Scala, Milan

Succeeds Toscanini as Music Director of La Scala, Milan, a post he holds until his retirement in 1953.

1939 – Berlin and Bayreuth

Makes a series of memorable recordings with the Berlin Philharmonic and leads a legendary Tristan in Bayreuth.

1946 – London debut

London musicians are astonished by a conductor ‘like no other’.

1953 – Illness and retirement

Suffers a heart attack shortly after completion of the celebrated recording of Puccini’s Tosca; this signals the start of a 14-year retirement from public life until his death in 1967.

The Essential Recording

Puccini Tosca

Maria Callas sop Giuseppe di Stefano ten Tito Gobbi bar Franco Calabrese bass Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan / Victor de Sabata

Warner Classics (12/53)

New commemorative release

DG has released a four-CD set of all of de Sabata’s recordings for DG and Decca including Brahms’s Symphony No 4, Beethoven’s Eroica, Respighi’s Feste Romane, Mozart’s Requiem, Richard Strauss’s Tod und Verklärung and shorter pieces by Kodály, Wagner, Sibelius and Verdi.