Max Bruch: Touching the Divine

Andrew Mellor

Thursday, August 20, 2020

He may have been less adventurous than Brahms but Bruch had a remarkable ear for melody, and in his late works he captured a profound level of expression, writes Andrew Mellor as we approach the centenary of the composer’s death

Max Bruch was born into a German music scene dominated by Mendelssohn and died a century ago within a decade of the first performance of Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire. His lifetime straddled seismic shifts in music’s language, its frame of reference and its place in society. Not that it bothered Bruch too much. Once established, the composer’s lyrical Romantic style would hardly change. On paper, much of the music he wrote in the last decade of his life resembled what he had produced 60 years earlier. Groundbreaking it was not.

Was Bruch born too late? Hardly. Brahms was positively expressionistic in comparison, while sticking to many of the same aesthetic ideals as his junior by five years. Bruch, in contrast, was change-resistant, full of noise about what he didn’t like, and as the straight-talking folk of Liverpool discovered, he was frequently cantankerous. That which established him as a composer is that which sustains his reputation today: his love for melody, his openness to it and his ability to conjure it up. Bruch’s cleaving to melody as both source and structure kept his ears alive to the truly beautiful, whatever its provenance.

On November 4, 1857, the composer bade farewell to his home town of Cologne with a concert there which included his Op 5 Piano Trio and the cantata Die Birken und die Erlen, Op 8 (for soprano, chorus and orchestra but on this occasion performed with voices and piano alone). Bruch wrote angrily about the ‘dull rattle-trap’ of the piano, a phrase that would foreshadow his famous remark, ‘The violin can sing a melody better than the piano can.’ Bruch, in fact, loathed the piano. A brief encounter with the charmless Op 88a Concerto for two pianos (which he refashioned from an organ suite) will readily prove it.

Unlike Brahms, Bruch was commercially successful and critically maligned precisely because he played it safe

For now, Bruch was on the way to Leipzig and the conservatory made famous by Mendelssohn, whose musical spirit still dominated the institution. He threw himself into Leipzig’s musical life and devoured performances of Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn and Schumann at the Gewandhaus. Already, melody was tugging at Bruch in a city ruled by the Mendelssohn school’s emphasis on post-Classical thematic augmentation (which would lead so many composers into a cul-de-sac of pedantic, empty music) and apparently bereft of singers. Bruch wrote to his former teacher in Cologne, Ferdinand Hiller, expressing disappointment that singing was not held in as high esteem in Saxony as it was in the Rhineland.

One reason for Bruch’s impatience was Die Birken und die Erlen’s readiness for performance. Bruch would make his reputation with secular cantatas like this one. After Leipzig, the composer settled in Mannheim and wrote the cantata Frithjof (1864). According to the composer’s biographer Christopher Fifield, this work kept his name before the German public throughout his life. It is based on an Icelandic saga and scored for two soloists, male choir and orchestra. It proved a hit in Leipzig and was conducted by Bruch in Vienna. ‘What I merely sensed in Die Loreley, I expressed clearly in Frithjof,’ the composer wrote in 1865, referring to the big-boned, stodgy opera he had completed in 1863, a piece that exposes the young composer’s shortcomings in the domain of theatrical music (it was issued in a recording last year, 3/19).

Heard via YouTube (where the only recording resides these days, courtesy of the Dutch Limburg Symphony Orchestra and Theo Timp), Frithjof certainly appears to possess a degree more charm and fluency than its operatic contemporary. For Bruch, it formed a prelude to the series of cantatas that would secure him, among other things, the principal conductorship of the Liverpool Philharmonic Society (1880-83). He was offered that job on the strength of his own performances on Merseyside of his Odysseus, Op 41, and Das Lied von der Glocke, Op 45.

As Europe moved towards the First World War, Bruch’s cantatas increased in domestic popularity but disappeared outside Germany. Das Lied von der Glocke (1878) is full of curvaceous vocal writing and earnest, beauteous music but can lack the last degree of spirit and atmosphere. Odysseus (1872) was Bruch’s most successful work in his lifetime and goes some way towards redressing those deficiencies. Brahms chose to conduct the piece in 1875 to mark the end of his conducting tenure in Vienna. In the 1930s, Sir Donald Francis Tovey rated it as Bruch’s finest: ‘I have not the slightest doubt that a revival […] would make a fresh and stirring impression on any audience that will listen,’ he wrote. No recording currently exists in the catalogue, but CPO – which (in collaboration with German broadcasters) seems determined to get through something like a ‘complete works’ – may well arrive at it soon.

Bruch knew that Brahms was the more adventurous composer – that the chief differential between the two was that his elder ‘took risks’. Bruch, it seems, felt a familial responsibility to follow the money. He was commercially successful and critically maligned precisely because he played it safe. He wasted no time striking up a relationship with Breitkopf when he arrived in Leipzig, but the inexperienced Bruch proved his insufficient business nous when he later came to agree terms with August Cranz for the publication (in 1868) of his Violin Concerto No 1. He readily signed away the royalty rights to his most enduring work and came bitterly to regret it.

‘You must dig into the scores of Symphonies Nos 2 and 3 to find the lines, the melody, the subtleties of scoring’ – Robert Trevino

Nine more concertante scores for violin and orchestra would follow, bringing with them the perennial question of why the Second and Third Concertos have never enjoyed the popularity of the First. The simple answer is in the listening. Concerto No 1 is pure inspiration to its successors’ apparent perspiration, even if the reality of their composition was wholly different. Bruch worked tirelessly writing and rewriting the First Concerto to get it to the point where Joseph Joachim could describe it as ‘the richest, most seductive’ written by a German. In the same breath, Joachim described Brahms’s concerto as the most serious – even more so than Bruch’s No 2 (1877), that is, which it followed by a year (dedicated to Joachim, while Bruch’s score was written for Pablo de Sarasate) and from which it stole quite some attention.

Yes, Bruch’s Concerto No 2 can feel a little congested against the Brahms: a complex stage play next to a sweeping monologue. But there are special moments in Bruch’s score, not least in the slow movement where the orchestral interludes range from the hushed to the climactic. Joachim commissioned Bruch’s Third (1891), written to an uppity classical design that prompted the composer to recall the distilled textures of the First Concerto (particularly in the slow movement) while reminding us that long-breathed lyricism is what Bruch does best.

The composer consciously sought the inspiration of folk tunes for his three violin concertos. In cases where he relaxed into that process and came clean about the provenance of his works in their titles, the results seem to be so much more refreshing for both performer and listener. As witness the soulful prayer for cello and orchestra Kol nidrei (Bruch encountered the traditional liturgical theme while conducting a Jewish choir in Berlin) and the Scottish Fantasy. The latter communicates its Sir Walter Scott-derived narrative with supreme ease courtesy of authentic melodies deftly handled. Bruch would return to folk song for his Serenade on Swedish Melodies, which arrived in 1916, almost half a century after the Violin Concerto No 1, at a time when old age had moved the composer towards a distillation of means and method. In getting out of the way of his chosen tunes, he did them a service.

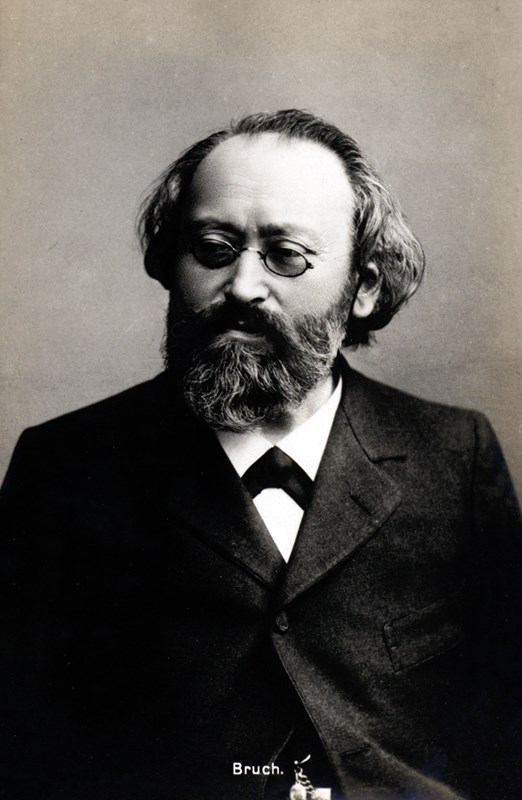

A sense of melancholy-tinged nostalgia is keenly felt in Bruch’s late works (photo: Valerie Jackson Harris Collection / Bridgeman Images)

Posterity has served the three violin concertos pretty fairly. Bruch the symphonist, however, could well use the attention of revisionism’s spotlight. The three symphonies were written between 1867 and 1883, the last as the composer departed Liverpool after a few professionally strained but personally fulfilled years (he married during his tenure and his daughter was born in the city). The stern Leipzig rule book hangs heavy over the hard-working First Symphony, before a greater degree of emotional flexibility emerges in the Second, which followed in 1870 and breathes easier, also demonstrating a more interesting handling of material. ‘Symphony No 2 enters Brahms 3 territory with these more opaque lines and all this ambiguity,’ says Robert Trevino, whose recordings of the complete symphonies with the Bamberg Symphony were issued by CPO in May.

The Third, based on material from far earlier in Bruch’s career, seems to pine for the composer’s native Rhineland behind its slight stiffness – a mark, perhaps, of how far from home he felt working in Liverpool and writing for New York, while already contracted to begin a conducting job in Breslau (as far as you can get from the Rhine while remaining in Germany). Parallels with the processional from Schumann’s own Rhenish Symphony are hard to avoid in the Adagio, which feels solemn to the point of sacred. Trevino extends the comparison to performance practice: ‘When you don’t bring the necessary nuance of approach to Schumann, his music is easily dismissible as poorly orchestrated. In reality you need to temper it all the time. And I really feel that when you get into Bruch’s Second and Third symphonies you have to dig into the scores to find where the lines are, where the melody is and what the subtleties of the scoring are. It’s about flexibility.’

Trevino, who feels much the same about the over-performed Violin Concerto No 1 (his recording with Ray Chen was issued two years ago, 9/18), summarises Bruch’s output as ‘beautiful, wholesome German lyrical music that didn’t break any moulds’. Yes, it can often lack that vital, indescribably extra dimension. But not always. Something happened to Bruch’s expression in the last years of his life, when his stubborn determination to resist the developments of Wagner and Liszt morphed into a form of liberating resignation – the conclusion that he no longer had a point to prove. A series of works written as the composer retired from his professorship at Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik saw him relaxing into a new, more profound level of expression.

‘You have to have the patience and courage to trust those melodies, make them really long and keep the tempo slow’ – Robert Plane

A catalyst was Bruch’s son Max Felix, a clarinettist who had progressed to competence and then excellence on the instrument. As Brahms had done two decades before him, Bruch became deeply interested in the sonority of the clarinet. In 1910, he wrote his Eight Pieces, Op 83, for clarinet, viola and piano for his son to play with two colleagues. ‘There is a carefree feeling to these pieces,’ says the clarinettist Robert Plane, who recorded the set for ASV in 2001; ‘some of them are in the minor key; you’d expect them to feel darker than they do but somehow the richness of colour makes them feel warm, even when they’re actually quite tragic. It’s like he’s finally thrown off some worries and just decided to do what he does best: write amazing melodies.’

The works are charming lyrical miniatures, each of a distinct mood but the whole set united by the sort of mellow richness that comes so naturally to the combination of viola and clarinet; Plane describes it as ‘a lovely blanket of sound’. Something in that combination evidently got under Bruch’s skin: in 1911, he followed the Eight Pieces with a ‘Double’ Concerto, Op 88, for clarinet, viola and orchestra which remains the composer’s best-kept secret. Gone is the virtuosity that characterised the early violin concertos. In its place is a reflective stillness, a depth of expression that renders every note meaningful and is underlined by a semblance of the autumnal. The two solo instruments trade in deep brown colours, even in the restrained caprice of the concerto’s finale.

Brahms lambasted Bruch for opening the second of his violin concertos with a slow movement, claiming it turned audiences off. In the Double Concerto, Bruch shows how little he cared. After a short cadenza-like recitative for both soloists, one of the composer’s most beautiful melodies unfurls at a languorously low speed, the solo instruments entwining themselves around one another. ‘You have to have the patience and courage to trust those melodies, make them really long and keep the tempo slow,’ says Plane. The instrument combination has precedents in Mozart, Schumann and even in Brahms. Plane acknowledges that the partnership of clarinet and viola has ‘an intrigue, and is amazingly rich and satisfying’.

It is odd indeed to consider this work of glowing, Romantic consolation as coming just months before Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire. But Bruch was not done with his late flowering, or its distinctive expression: 1918 and the desolate aftermath of the First World War brought forth his most celebrated chamber works, including the two string quintets in which the sense of melancholy-tinged nostalgia is felt even more. Again, his music has slowed; there are effectively four slow movements between these two works, with blissfully melodic music at every turn, as realised by the Gramophone Award-nominated 2016 recording from the Nash Ensemble. ‘What we have here is probably Bruch’s finest string chamber work,’ suggests Richard Bratby in his review (5/17).

A year after he’d written the quintets, Bruch’s wife, Clara Tuczek, died. The composer followed her in 1920. His epitaph would read ‘Music is the Language of God’. Does his work get close to the divine? Yes, and more often than we think.

Must-hear Bruch

Symphonies Nos 1, 2 and 3

Bamberg Symphony / Robert Trevino

CPO

New recordings of the symphonies in which Trevino promises flexibility and fastidious attention to detail.

Eight Pieces for clarinet, viola and piano

Philon Trio

Analekta

Bruch’s late, family-induced love affair with the clarinet found its first expression in these varied works.

Concerto for clarinet, viola and orchestra

Ecesu Sertesen cl Kyoungmin Park va ORF Vienna RSO / Howard Griffiths

Sony Classical

Bruch relishes the combination of clarinet and viola here.

String Quintets. Octet

Nash Ensemble

Hyperion

A Gramophone Award-nominated recording of Bruch’s chamber music from the aftermath of the First World War.

This article originally appeared in the August 2020 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue – subscribe today!