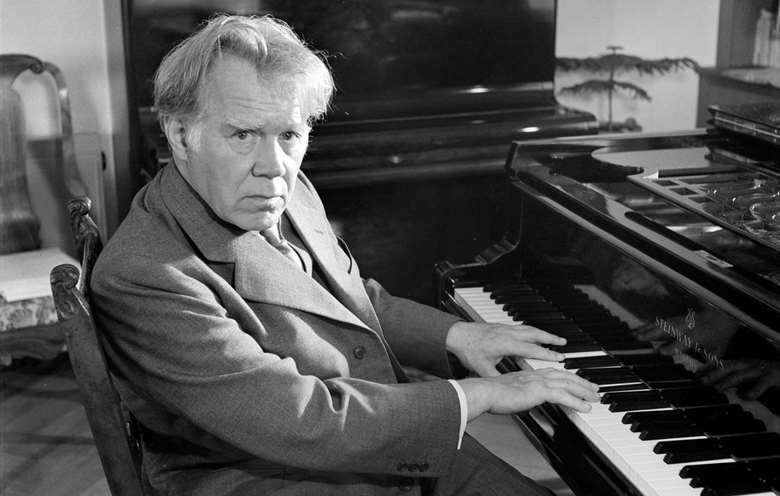

Icon: Edwin Fischer

Stephen Cera

Monday, January 9, 2023

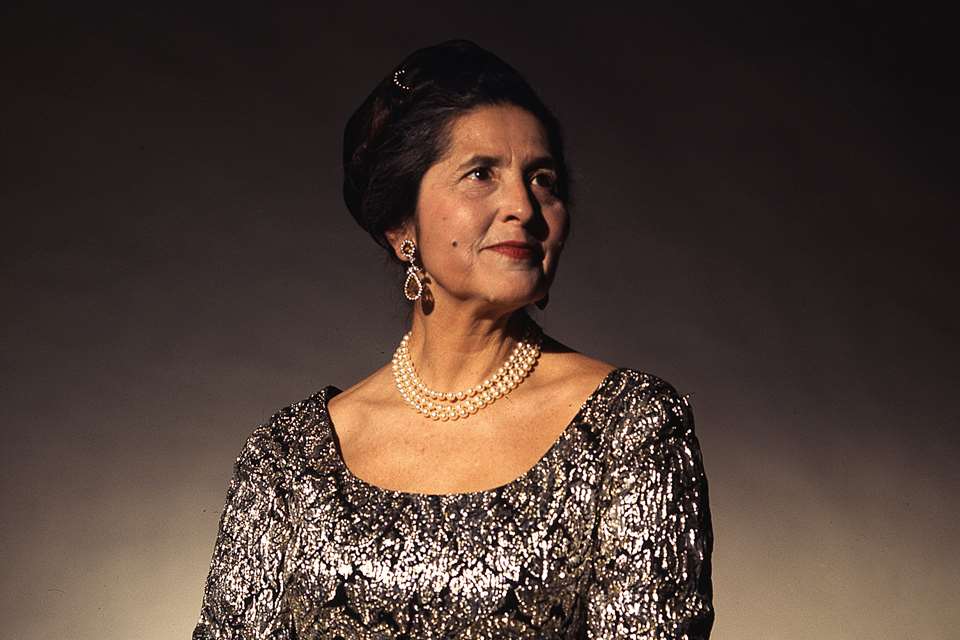

Celebrating the qualities of his playing and the many and varied achievements of this Swiss pianist, Stephen Cera highlights the fact that he deserves greater recognition as an innovator

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter