Toscanini: the man behind the myth

Gramophone

Tuesday, January 3, 2017

A classic Gramophone article from June 1943 by FW Gaisberg

In a captivating article in the January 2017 issue, Richard Osborne reflects on the tumultuous career of the legendary conductor Arturo Toscanini (subscribe here). To celebrate the latest issue, we present a feature about the conductor's last days extracted from Gramophone's unrivalled digital archive.

Even on my first visit to Milan the name and genius of Arturo Toscanini was impressed upon me. As early as 1902 I had heard him conduct his Turin Orchestra in Elgar's Enigma Variations and before that I witnessed his conducting of the premiere of the opera Germania at La Scala, when I heard Caruso for the first time. Who could go to Milan year after year, as I did for 40 years, without becoming saturated with Toscanini lore. My friend Carlo Sabajno worshipped him as a divinity. Carlo was his maestro substitute during the historic Turin Exhibition of 1898 when the master staggered musical Italy by conducting 43 concerts by memory. No wonder the youngsters of that day worshipped and tried to emulate him. Future Weingartners and Mengelbergs would hang around him to run his errands: 'Vai compratemi un pacchetto di macedonia' or 'un Toscano' ('Go buy me a box of cigarettes' or 'a Tuscan cigar'). He loved those black, vile-smelling Italian cigars.

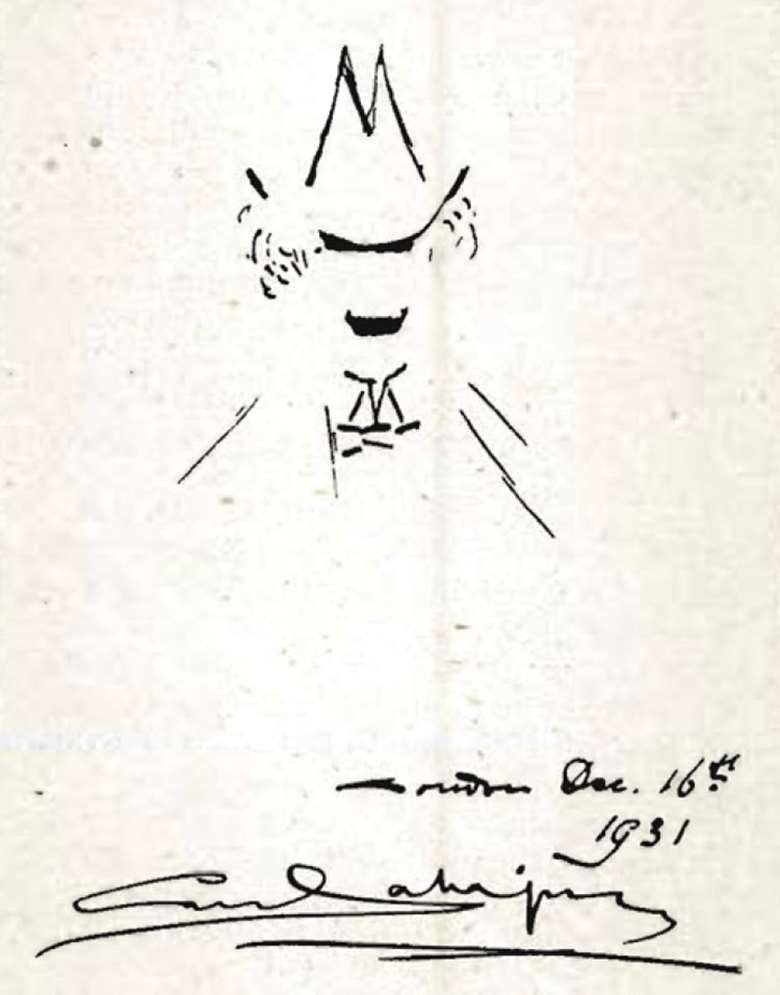

Many stories have been told ofToscanini's uncompromising attitude towards singers. Undoubtedly many artists have had occasion to nurse bruises after rehearsals, when things have not gone well. Yet he was deeply appreciative of merit and intelligence in singers, amongst whom he counted some of his truest friends. Strange bed-fellows, Chaliapin and Toscanini, yet they got on well together in their many performances of Boris and Mefistofele, both at the La Scala and the Metropolitan before World War I.

Hardly had Chaliapin arrived in England after the Revolution in Russia when he received a cable from Toscanini inviting him to sing Boris at La Scala, where he was then in charge. The message was couched in the most flattering and friendly terms and Chaliapin regretted that commitments already entered into in America made it impossible for him to accept. Whenever they met they were demonstratively affectionate and genuinely relished each other's company. The part of Boris was eventually given to Zilianski. At a rehearsal this artist inserted an effect not in the score. Down came Toscanini's stick with a slap-bang and sharply rang out the Maestro's familiar 'Ma che! Ma che! cosa fai!' ('Now, now! What are you up to!') and Zilianski's: 'Maestro, but that's the way Chaliapin does it .' Then Toscanini's retort: 'Ma Chaliapin e un grande artista and who are you?'

Toscanini seems to be chronically testy and always on his guard against boring people and thick-skulled singers. To some of these who would attempt to placate him with 'Commendatore' he would snap back 'Mi chiamo Maestro'. During his reign at La Scala the stage doorkeeper would give out the barometer readings for the day as one passed through the door: 'Oggi calmo' or 'Oggi tempesto' ('Today calm' or 'Today storm'). All this could be attributed to health - he is a lifelong sufferer from bad digestion, and his wife, Carlotta, is always near him to prepare his special dishes and nurse him. A few intelligent singers of the type of Pertile, Stabile, Dusolina Giannini, Baccaloni, etc. receive consideration and kindness from him. Many others would have a sadder story to tell.

Of the men of the orchestra, once they are accepted and established, he kindly, almost fatherly, calls them 'figliuolo mio' ('my little son'); they love this. To be thus addressed is to them like the kiss of a relenting mistress. His reprimands are always merited and they well know it.

I asked a very good friend of Toscanini's what made him so habitually abrupt and unapproachable. He replied that he thought he was an unhappy man by nature; then he changed his mind and said it may be his chronically bad digestion.

There was a young German producer (Herr Lert) engaged specially from Berlinl for the Scala production of Tristan. I met him early one morning outside the theatre in tears. 'I can't stand it,' he said. 'Last night, after the performance, he had me on a lightning rehearsal up to three this morning; then he telephoned to tell me how bad I am and to meet him at 8 o'clock for more trials. Does he think I don't know my job? I am getting out of here, back to Berlin.' As he spoke the Maestro, bright and alert, appeared from behind the portio where we were standing and, seeing the despondent Lert, he gave him the 'figliuolo mio' and asked him to forgive the telephone call. He added that he had been worked up and had to get his spleen off, and Lert was the first one he lit upon. As the Maestro passed on, a flush of pleasure spread over the German's face and he said to me, 'Oh, so that's how it is!' and gave a sigh of relief.

Toscanini's reputation as an uncompromising disciplinarian at rehearsals has justification, but it was earned in Italy, where symphony orchestra concerts was an acquired taste and orchestral standards had been allowed to slide. The habit of cajoling and driving the players thus fastened itself on him. I noticed that there was less of this when he directed the old Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and, upon sober reflection, it could have been for no other reason than that this organisation was a very plastic body of long tradition, even if their average age was considerably higher than any other society he had ever confronted. Anton Weiss, their secretary, gloated to me when he had secured Toscanini and shivered when he reflected on the baptism of fire that awaited the men. When I met him after the first rehearsal he was the most surprised man as he reported to me that there had been no eruptions and, indeed, throughout his collaboration with these experienced and responsive veterans they worked in cordial relationship. Burghauser, the President of the orchestra, and Anton Weiss assumed the credit for prevailing on Toscanini to become the conductor and patron of their orchestra, beginning with a series of symphonic concerts in Vienna and later the Salzburg Festival Opera performances. The proceeds went to increase the orchestral Pension Fund to a handsome amount. After dissociating himself from La Scala Opera in 1929 and declaring he would thereafter devote himself principally to symphonic concerts, it was a great achievement for friends Weiss and Burghauser to secure him for their opera.

So successful were the Salzburg Festival Seasons when Toscanini presided there, that it made that lovely town a mecca of musicians and brought to it fortune and world fame. Fidelio, Falstaff, Zauberflöte, Meistersinger were his operas. I attended these performances and most of the rehearsals and count it as one of the rarest experiences of my life.

The Salzburg Festival is a joint enterprise of the Salzburg Municipality, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and the Vienna Opera Choral Society. They gave Toscanini every possible support to carry out his ideas in production, cast and performance. Toscanini worked like a slave, enjoyed every minute of it and called it a holiday. He was surrounded by congenial spirits like Stabile, Baccaloni, Dusolina Giannini and a relay of Italian friends from Milan who invaded Salzburg through the Brenner Pass in cars and trains, in spite of the bristling guns and frontier friction. I hovered around during those three seasons 1935, 1936 and 1937, enjoying it immensely, but always with the hope of recording gems of production. I had consolation in plenty of lounging in the Bazar Cafe, where one met the great and near great in this oasis of bliss in a world of storms. I had long decided that recording during the Festival was hopelessly impossible, where singers, musicians and the theatre were employed 24 hours a day between rehearsals and performance.

I looked forward to the Meistersinger and had a pass to attend the Probe Generale. The good burghers of Salzburg looked upon general rehearsals as their special monopoly and, without cost to themselves, invited their friends to attend as their guests, thus in a most economic way wiping off old scores. On the occasion of this rehearsal over 2000 expectant Salzburgers filled the theatre. I was with Madame Carlotta and her son-in-law, Count Castelbarco. I heard her uneasily muttering, 'The Maestro will certainly object to rehearsing with a full audience.' Sure enough, Toscanini smartly stepped on the podium, looked around, and with a glance of dark annoyance, promptly left. It took just five minutes to turn those disappointed and angry burghers into the street. Only when the house was cleared did the rehearsal start.

When in congenial company, Toscanini can also tell a good story, well garnished with the dialects of Italy. If he ran into his friend Chaliapin at Paganis Restaurant or in the Savoy Grill, it usually led to an exchange of one or more stories, at which they were both past masters in telling and enjoying (reciprocity is the basis of storytelling). One of his stories occurs to me. It was about an oboe player he took with him every season to New York. The man, a Neapolitan, became a chronic grumbler, complaining that he and his wife found the cost of living in New York too high and he must have more money. Toscanini would meet the fellow's grievance with an advance, but back he would come again, until he became a nuisance. 'Could the wife dance in the Ballet,' asked Toscanini, searching to accommodate the matter. The Neapolitan puffed out his cheeks and made an eloquent sweep of his arms to indicate the wife's elephantine proportions. 'Good,' responded the Maestro, 'put her name down for the Chorus.'

Toscanini has three very human traits; he likes to polish his own boots, he enjoys smoking black Toscano cigars and in his sleep he grinds his teeth. In the Simplon Express my friend discovered these peculiarities when he occupied the upper berth in the 8.20pm express to Milan and Toscanini occupied the lower. The next morning, walking up and down the platform at the frontier station, he asked, 'Did you sleep well?' to which my friend replied, 'Not so badly. I would have slept better but you kept me awake grinding your teeth.' The Maestro laughed and thought it a great joke. My friend did not add that the smell of his black Toscano was another disturbing factor.

There is a wonderful film scenario yet to be written and filmed on that page of Toscanini's life dealing with the courageous stand he took on the persecution of the Jews and the rule of the Dictators. No other musician, barring Pablo Casals, has paid so high a price for his convictions. It stamps him as one of the bravest of the brave.

Fritz Kreisler himself told of a visit he paid Toscanini in New York, when he saw him handling a cable just received from Winifred Wagner urging him to take charge of the 1933 Bayreuth Season. He had brilliantly conducted there in 1930 and when Siegfried died that year he promised the widow he would help her out during the 1933 season, but he had reckoned without the Nazi Party coming to power with their anti-Jewish programme. How could he fulfil his promise to her under these conditions? It was against all his sense of human justice to condone these actions by returning to Bayreuth. Kreisler said he entered the hotel apartment and saw the Maestro surrounded by photographs of Wagner, Bayreuth and the Wagner family. In his hand he held an original manuscript of the master, a gift of Winifred. Together they worded a cable of refusal, but it was a bitter pill for Toscanini.

Another part of the scenario should depict the trying but successful season conducting the Palestine Orchestra, all proceeds of which were to benefit the Jewish cause, his own fees included. He had actually promised to return for the 1938 season and had firmly laid his plans to do this. However, when he visited his great friend Sir Louis Sterling and told him of his intention, he promptly took steps to prevent so foolhardy an undertaking, in view of the grave turn of political events in Europe. It was no easy matter to deter Toscanini and it was only by great good fortune that Sir Louis was able to contact Dr Hertz, Chief Rabbi of Palestine, a few minutes before his departure for the Croydon aerodrome. He immediately sent Toscanini a peremptory command to abandon the trip because of political unrest.

To this episode must be added Toscanini's last departure from his homeland and the obstacles placed in his way by the Italian authorities' refusal of an exit permit or permission to carry out funds and personal belongings. He was virtually a prisoner in his own home. Finally, when he and his family did leave for France, they were held up at the frontier, where David Sarhoff, the RCA President with whom he had a contract to conduct the great NBC Orchestra for radio concerts, met him with a powerful car and motored the family to Havre to embark for New York. But Toscanini returned to the Lucerne Festival of I939 and eventually was marooned there when war broke out. He was one of the five thousand more or less worried passengers who embarked on the SS George Washington from Bordeaux in October, I939. During the entire trip he barely issued from his cabin.

Arturo Toscanini was 76 years old on March 25, 1943, and from all accounts is still going strong. The only talking machine company ever to have a contract direct with Toscanini was the Gramophone Co, Ltd. The Victor Company had an exclusive contract with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and the National Broadcasting Corporation Orchestra and through these they also enjoyed his service for the recordings that appear on their catalogues. In the same way the Gramophone Company, through their contract with the British Broadcasting Corporation Orchestra, secured those excellent records on their lists, including Beethoven's Symphonies Nos 1 and 6 in 1937 and No 4 and the Leonora No 1 in 1939. The recording of each of these called upon the greatest patience and preparation by the recording staff. He was never asked to make compromises for the machine, nor would he have done so. In my book, The Music Goes Round, I have told how I assisted Owen Mase of the BBC in securing Toscanini for their 1937 Musical Festival and some of the stories of studio recording experiences and when 'spot' recording was carried out during concert performances. How every time the timpanist made a thunderous attack on his drums the controller would have a heart attack or when, in some soft violoncello passage, Toscanini's voice singing the melody would drown the solo instrument. Pianissimos inaudible above the surface of the disc or fortissimos that sent stabs across into the next groove. Yet with all the ups and downs, there still remains an ample list of great works capable of showing future generations the genius of the greatest conductor of our time.

This article originally appeared in the June 1943 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing to Gramophone, visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe