Sibelius's Violin Concerto: an in-depth guide to the best recordings

Monday, June 6, 2022

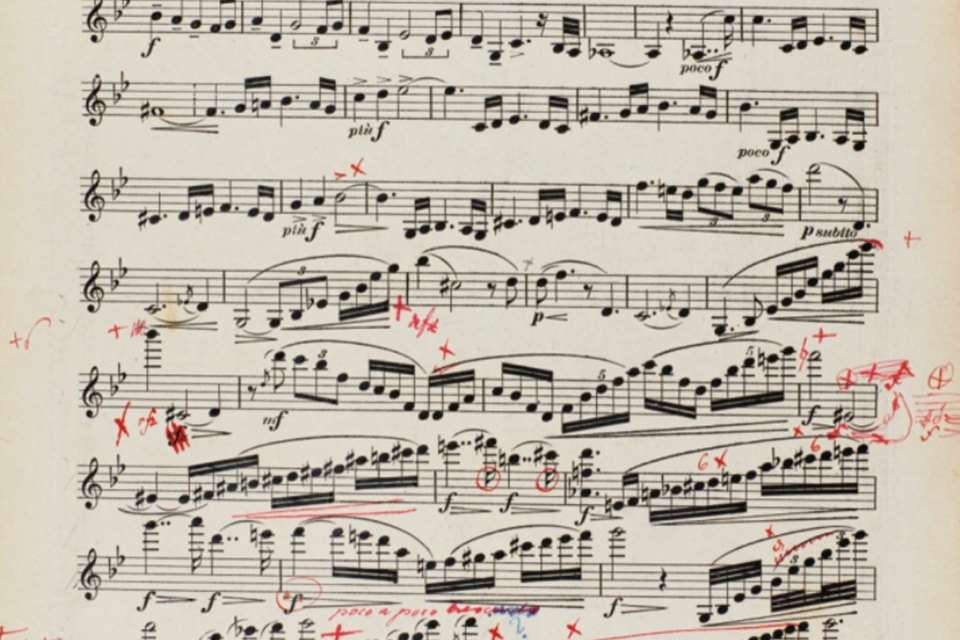

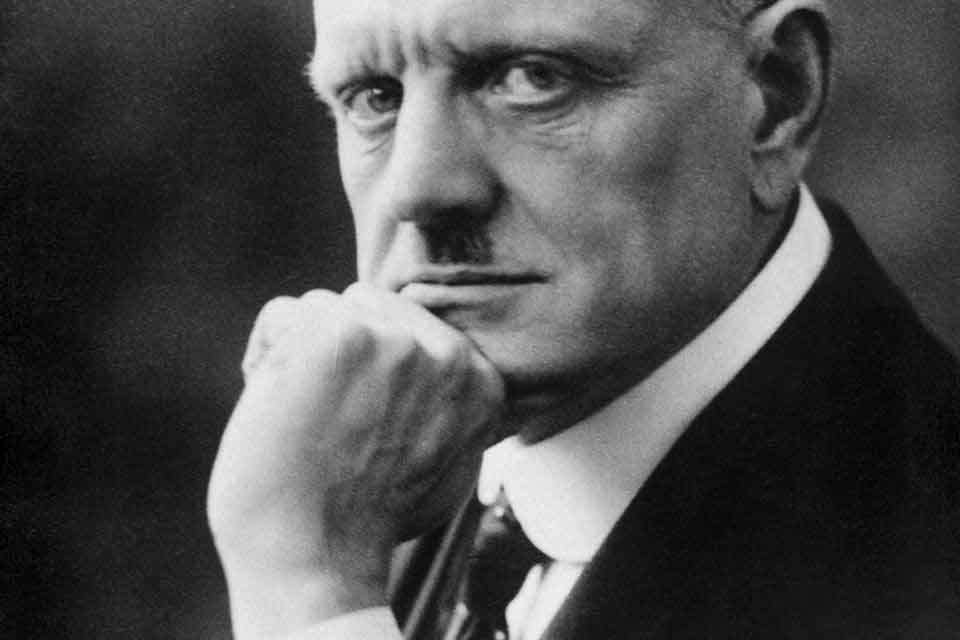

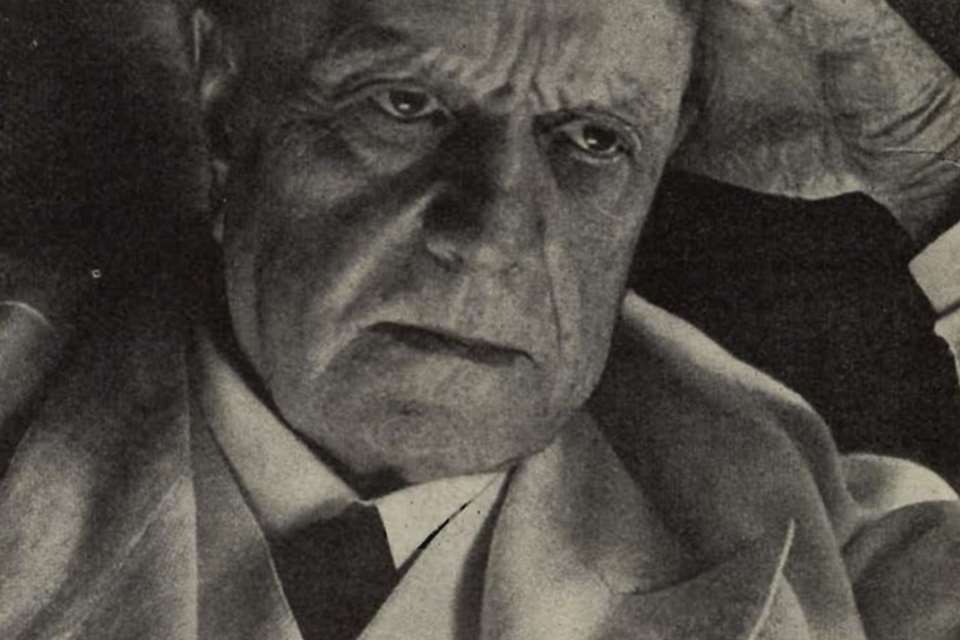

Jean Sibelius’s sole concerto, in which every note is valuable, according to Ida Haendel, remains among his most popular works. David Gutman surveys recordings reaching back nine decades

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter