Rachmaninov's Piano Concerto No 2: A quick guide to the best recordings

Gramophone

Sunday, January 1, 2023

A quick guide to the greatest recordings of Rachmaninov's much-loved concerto

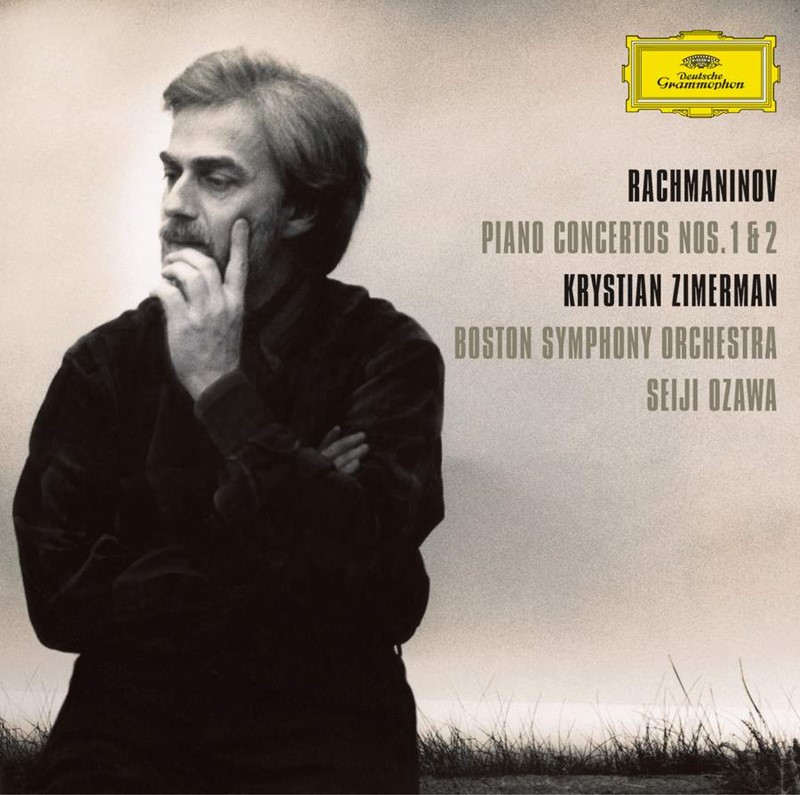

Piano Concertos Nos 1 & 2

Krystian Zimerman pf Boston Symphony Orchestra / Seiji Ozawa

DG

The catalogue may bulge with recordings of these two concertos, yet the verve and poetry of these performances somehow forbid comparison, even at the most exalted level. Zimerman claims that Rachmaninov says everything there is to say about the First Concerto in his own performance. But had Rachmaninov heard Zimerman he might have been envious. Zimerman opens in a blaze of rhetorical glory before skittering through the first Vivace with the sort of winged brilliance that will reduce lesser pianists to despair. The cadenza is overwhelming, and at 4'36" in the central Andante’s starry ascent his rubato tugs painfully at the heartstrings. In the finale, despite a dizzying tempo, every one of the teeming notes is pinpointed with shining clarity.

The Second Concerto also burns and coruscates in all its first heat. A romantic to his fingertips, Zimerman inflects one familiar theme after another with a yearning, bittersweet intensity that he equates in his interview with first love. Every page is alive with a sense of wonder at Rachmaninov’s genius. Seiji Ozawa and the Boston orchestra are ideal partners, and DG’s sound and balance are fully worthy of this memorable release.

Piano Concertos Nos 1 & 2

Leif Ove Andsnes pf Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Antonio Pappano

Warner Classics

With no shortage of fine versions of this pairing from which to choose, EMI must rely on the undoubted selling power of its Norwegian star to make this release stand out from the rest. It is certainly a worthy contender for the Top Ten when aided by the world-class Berlin Phil, a conductor who is in the Barbirolli class of adroit accompanists, superb recorded sound and a beautifully voiced piano.

With judicious tempi (though, as is now customary, slightly slower than the composer’s) and a well-nigh ideal balance between piano and orchestra, instrumental detail is tellingly observed, such as the bassoon and clarinet counterpoint at the beginning of the second movement of the First Concerto and the triangle in its finale, both well integrated into the sound picture, even if there is a hint of the engineer’s hand.

Nor is there anything mannered about the -soloist, though some may wish he was slightly less well-mannered. Andsnes here gives the lie to those who find his playing on the cool side of emotional but he is always the reliable guest who never gets drunk, no matter how much alcohol he has consumed. The fiery section of the cadenza to the First Concerto, for example, runs out of steam in the final bars to which Byron Janis, for instance, brings a despairing vehemence.

The Second Concerto (live, as opposed to the studio First, but without any appreciable difference in acoustic and balance) is, similarly, given a Rolls-Royce reading with which only the pickiest could find fault. The last movement, though, is something special and the final appearance of its glorious second subject, greeted with a mighty timpani wallop and braying brass, is heart-stopping. The audience rightly roar their approval.

Piano Concerto No 2, etc

Alexandre Tharaud pf Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra / Alexander Vedernikov

Erato

Another ‘Rach 2’ dropping on to the doormat makes the heart rather sink. Except…the pianist is the wonderfully gifted Alexandre Tharaud, and the orchestra is the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, and, let’s see, the conductor is the excellent Alexander Vedernikov. This might be special.

So it proves. After the famous introductory bars – following the score rather than the composer’s recording – the sweeping first subject enters faster, thankfully, than Richter’s celebrated account but with the same majestic assurance. Various boxes are ticked as the movement proceeds, including a properly swaggering alla marcia, emphasised by the piano’s forward placement in the sound picture. The clarinet solo in the Adagio is as tender and vulnerable as you’ll ever hear (with or without its association with Brief Encounter, this one is particularly poignant), and so to the finale, notable for the soloist’s exemplary clarity and the orchestra’s alternately lusty and sensitive playing. On the last page, Tharaud and Vedernikov decide to share the battle honours and storm home as equal partners to thrilling effect.

The concerto is followed not by another but by the five early Morceaux de fantaisie (1892), the second of which is the ubiquitous Prelude in C sharp minor (or ‘It’, as the composer came to call it). If you think you never want to hear the piece again, then listen to this account, a miracle of musical storytelling, a pessimistic interlude between the lovelorn beauty of the ‘Elégie’ (No 1) and ‘Mélodie’ (No 3). The opening of ‘Polichinelle’ (No 4) struck me for the first time as a near-quote from ‘Kangaroos’ in Carnival of the Animals.

As a further contrast, soprano Sabine Devieilhe joins Tharaud in the ‘Vocalise’ (lovely but without quite the same poise as Natalie Dessay or the incomparable Anna Moffo). The disc ends with two more pianists joining Tharaud for the Two Pieces for Piano, Six Hands (1890 91): not Rachmaninov at his best, it doesn’t work as a piece of programming and is thus the only part of the disc that is not completely successful.

Piano Concertos Nos 1-4

Vladimir Ashkenazy pf London Symphony Orchestra / André Previn

Decca

Recorded 1970-72

Despite the recording dates, the sound and balance are superb, and there’s nothing to cloud your sense of Ashkenazy’s greatness in all these works. From him every page declares Rachmaninov’s nationality, his indelibly Russian nature. What nobility of feeling and what dark regions of the imagination he relishes and explores in page after page of the Third Concerto. Significantly his opening is a very moderate Allegro ma non tanto, later allowing him an expansiveness and imaginative scope hard to find in other more ‘driven’ or hectic performances. His rubato is as natural as it’s distinctive, and his way of easing from one idea to another shows him at his most intimately and romantically responsive. There are no cuts, and his choice of the bigger of the two cadenzas is entirely apt, given the breadth of his conception. Even the skittering figurations and volleys of repeated notes just before the close of the central Intermezzo can’t tempt Ashkenazy into display and he’s quicker than any other pianist to find a touch of wistfulness beneath Rachmaninov’s occasional outer playfulness (the scherzando episode in the finale).

Such imaginative fervour and delicacy are just as central to Ashkenazy’s other performances. His steep unmarked decrescendo at the close of the First Concerto’s opening rhetorical gesture is symptomatic of his Romantic bias, his love of the music’s interior glow. And despite his prodigious command in, say, the final pages of both the First and Fourth Concertos, there’s never a hint of bombast or a more superficial brand of fire-and-brimstone virtuosity. Previn works hand in glove with his soloist. Clearly, this is no one-night partnership but the product of the greatest musical sympathy. The opening of the Third Concerto’s Intermezzo could hardly be given with a more idiomatic, brooding melancholy, a perfect introduction for all that’s to follow. If you want playing which captures Rachmaninov’s always elusive, opalescent centre then Ashkenazy is hard to beat.

Piano Concertos Nos 1-4. Paganini Rhapsody

Stephen Hough pf Dallas Symphony Orchestra / Andrew Litton

Hyperion

Hough. Litton. Rachmaninov concertos. Hyperion. Already a mouth-watering prospect, isn’t it? So, like the old Fry’s Five Boys chocolate advert, does Anticipation match Realisation in these five much-recorded confections?

The answer is ‘yes’ on almost every level. Culled from one or more live performances the concertos may be, but they manifest a real sense of occasion. Hough has clearly been burning to record these pieces for years. Litton is one of the world’s most adept accompanists. He and his Dallas players offer exemplary support, with bright precision, purring strings and a judiciously blended brass section. A handsomely voiced piano brings a near-perfect balance; only in the final pages of the studio-made Paganini Rhapsody does Hough struggle to make himself heard. Unlike most of his peers, he takes the composer at his word (scores and recordings) in matters of tempo, dynamics and the performance practice of Rachmaninov’s musical language, as he makes clear in a trenchant apologia in the superb booklet-note (by David Fanning).

Where Wild and Argerich seem glib in the cadenzas of the First and Third Concertos respectively, Hough imparts the right sense of heroic struggle; not even Rachmaninov caresses the second subject of the First Concerto’s finale so beguilingly; the notoriously tricky opening pages of the Second Concerto’s finale are dispatched with breathtaking élan, as is the last movement of the Third Concerto. It’s quite an achievement when each of Hough’s five performances rivals the greatest versions recorded individually by other pianists (the younger Horowitz in the Third, for example, Michelangeli in the Fourth). As a competitive set, that from the much-lamented Rafael Orozco comes close to matching Hough’s fleet-fingered ardour, but is less impressively re-corded; Howard Shelley offers a convincing, slower alternative with powerful, weighty tone. Overall, though, only Earl Wild and, before that, Rachmaninov himself truly convey the composer’s intentions with such miraculous fluency, passion and stylistic integrity.

Welcome to Gramophone ...

We have been writing about classical music for our dedicated and knowledgeable readers since 1923 and we would love you to join them.

Subscribing to Gramophone is easy, you can choose how you want to enjoy each new issue (our beautifully produced printed magazine or the digital edition, or both) and also whether you would like access to our complete digital archive (stretching back to our very first issue in April 1923) and unparalleled Reviews Database, covering 50,000 albums and written by leading experts in their field.

To find the perfect subscription for you, simply visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe