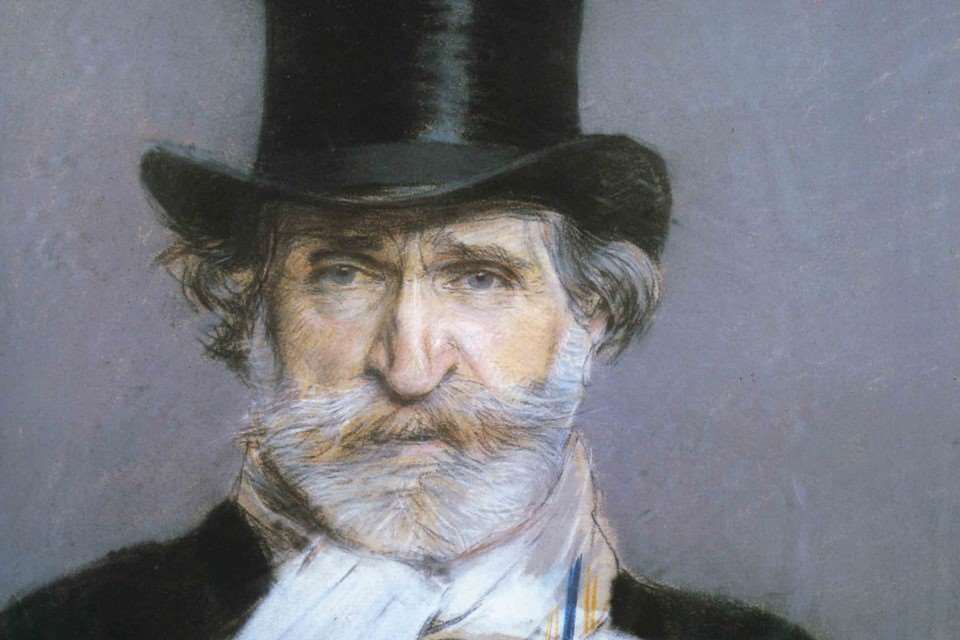

Top 10 Classical era Composers

Monday, January 24, 2022

The Classical era was dominated by many of the greatest composers in the history of music, including Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn and Schubert

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter