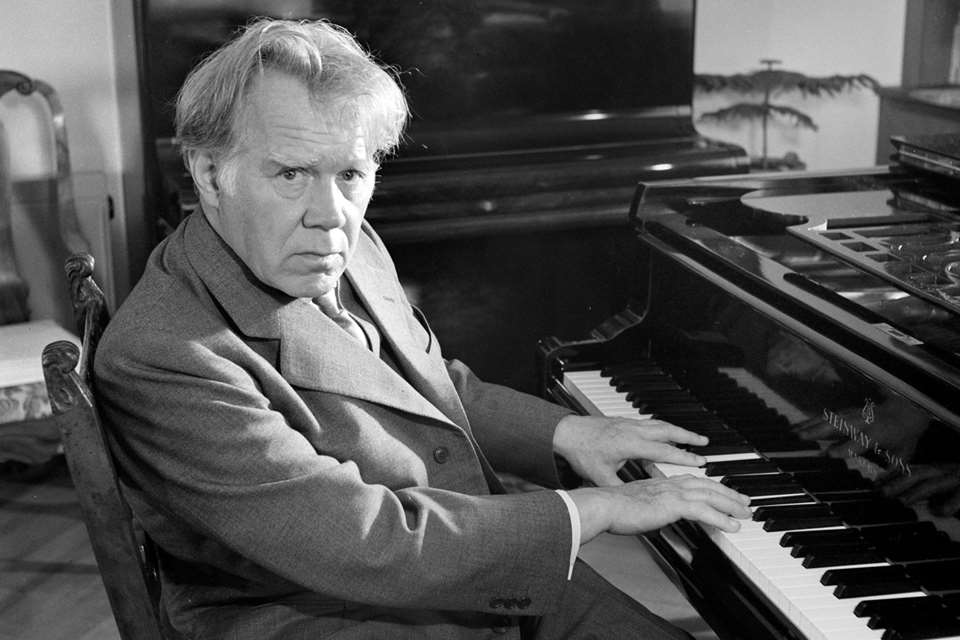

Leon Fleisher: how the pianist triumphed over adversity

Michael McManus

Wednesday, May 22, 2024

Although he lost the use of his right hand while only in his thirties, this pianist refused to be thwarted – Michael McManus fondly remembers and pays tribute to an all-American hero

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter