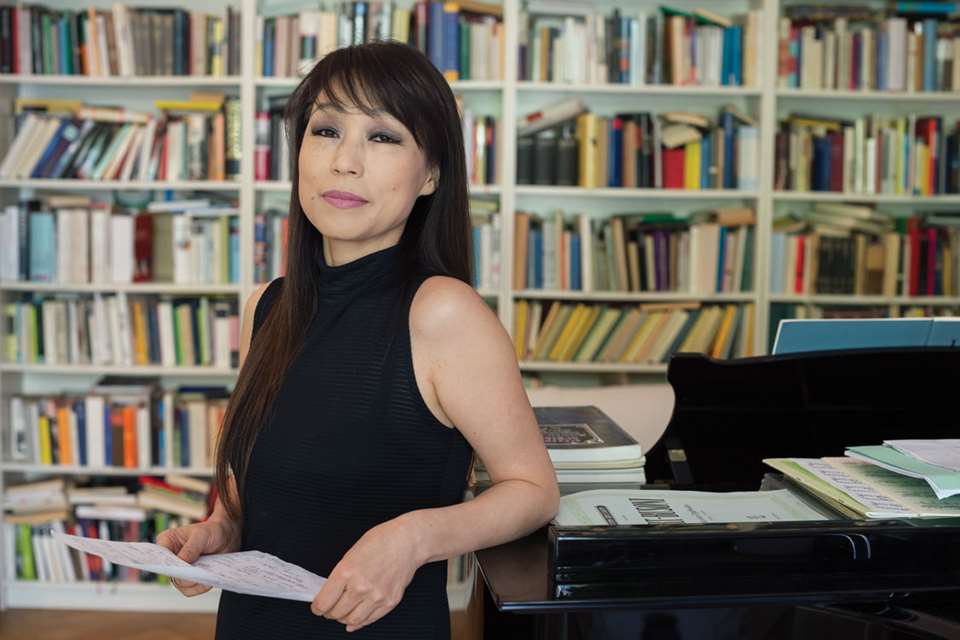

What makes Meredith Monk one of contemporary music’s most original, individual, and innovative figures?

Pwyll ap Siôn

Thursday, January 19, 2023

This US composer Meredith Monk has continued to work in multiple art forms and to break the mould for more than 50 years

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter